Foreword

The Financial Stability Review (FSR) assesses developments relevant for financial stability, including identifying and prioritising the main sources of systemic risk and vulnerabilities for the euro area financial system – comprising intermediaries, markets and market infrastructures. It does so to promote awareness of these systemic risks among policymakers, the financial industry and the public at large, with the ultimate goal of promoting financial stability.

Financial stability can be defined as a condition in which the financial system – which comprises financial intermediaries, markets and market infrastructures – is capable of withstanding shocks and the unravelling of financial imbalances. This mitigates the likelihood of disruptions in the financial intermediation process that are systemic, that is, severe enough to trigger a material contraction of real economic activity.

The FSR also plays an important role in relation to the ECB’s microprudential and macroprudential competences. By providing a financial system-wide assessment of risks and vulnerabilities, the Review provides key input to the ECB’s macroprudential policy analysis. Such a euro area system-wide dimension is an important complement to microprudential banking supervision, which is more focused on the soundness of individual institutions. While the ECB’s roles in the macroprudential and microprudential domains have a predominant banking sector focus, the FSR focuses on the risks and vulnerabilities of the financial system at large, including – in addition to banks – activities involving non-bank financial intermediaries, financial markets and market infrastructures.

In addition to its usual overview of current developments relevant for euro area financial stability, this Review includes three special features aimed at deepening the ECB’s financial stability analysis and broadening the basis for macroprudential policymaking. The first special feature examines financial stability risks stemming from climate change, in particular examining the exposure of financial institutions to climate risk-sensitive assets. The second sets out new ways to model the risk of contagion spreading through the euro area banking sector. The third considers how macroprudential policy responses might take account of changes in macroeconomic conditions. The Review has been prepared with the involvement of the ESCB Financial Stability Committee, which assists the decision-making bodies of the ECB in the fulfilment of their tasks.

Luis de Guindos

Vice-President of the European Central Bank

Overview

The euro area financial stability environment has become more challenging. Risks to economic growth are tilted to the downside and remain prominent. Volatility in financial markets around the turn of the year illustrated risks that could arise from global and euro area growth surprises. Persistent downside risks to growth reinforce the need to strengthen the balance sheets of highly indebted firms and governments, as well as a euro area banking sector beset by weak profitability.

Risks to economic growth remain tilted to the downside

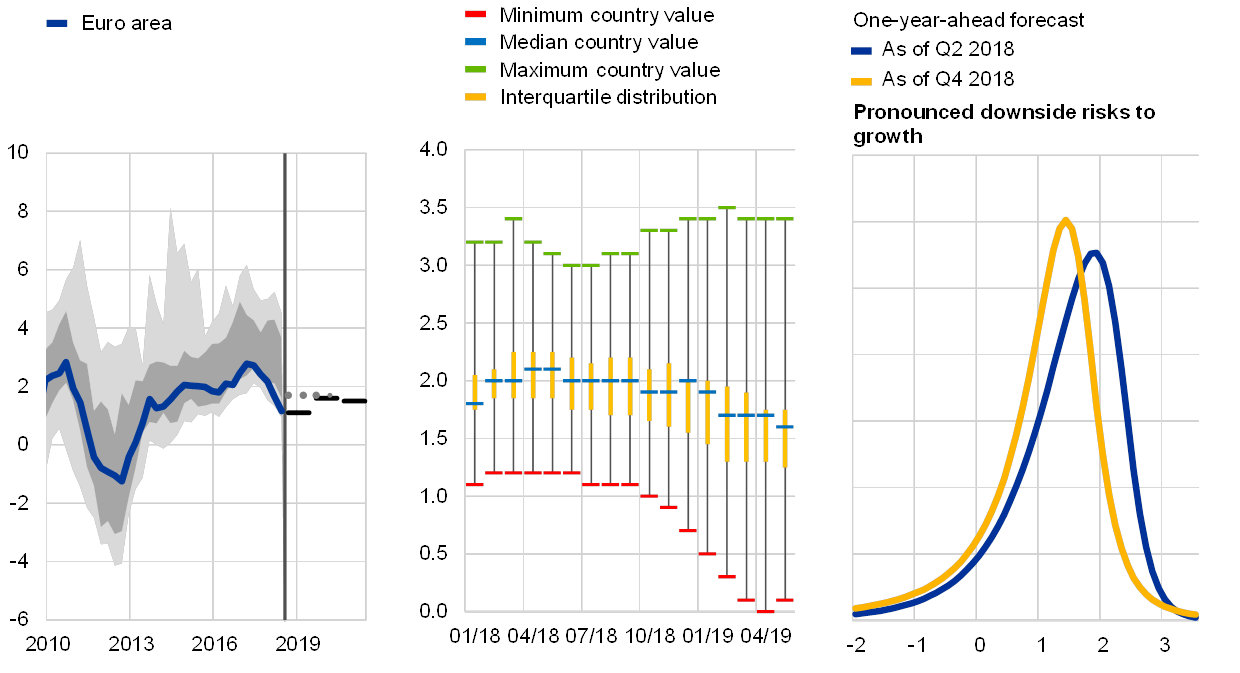

Euro area economic growth prospects have softened somewhat, in tandem with a weakening of growth prospects around the globe. ECB projections confirm a weakening in economic growth prospects in the first half of the year, consistent with downward revisions by analysts, with a growing cross-country dispersion of growth prospects this year (see Chart 1, left and middle panels). Looking ahead over the medium term, a gradual dissipation of global and domestic headwinds is expected, allowing fundamental factors to help the euro area expansion regain traction. In fact, supportive financing conditions and solid wage growth continue to underpin the ongoing euro area expansion. This baseline scenario is, however, subject to persistent downside risks – notably uncertainty in the global economy spilling over to the external sector (see Chart 1, right panel). This could include uncertainty arising from political processes relating to global trade or a disorderly Brexit (see Box 1). Taken together, the available data suggest that the economic recovery in the euro area has been delayed but not derailed.

Chart 1

Downside risks to the growth outlook appear prominent

Annual real GDP growth rates for the euro area and ECB GDP growth forecast for 2019-21 (left panel); real GDP growth expectations by market participants for 2019 across euro area countries (middle panel); future expected GDP distributions derived from the Financial Stability Risk Index (right panel)

(left panel: 2010-21, annual growth rates; middle panel: Jan. 2018-May 2019, annual growth rates; right panel: near-term expected euro area real GDP distributions)

Sources: Consensus Economics, Thomson Reuters Datastream, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the forecasts are based on the March 2019 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area (solid lines) and the December 2018 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections (dotted lines). The darker grey shaded area represents the range between the 25th and 75th percentiles, while the lighter grey shaded area displays the range between the 10th and 90th percentiles. Middle panel: the forecasts are taken from Consensus Economics. Right panel: the distributions are based on the ECB’s Financial Stability Risk Index. For further details of the methodology, see the May 2018 FSR special feature entitled “A new Financial Stability Risk Index (FSRI) to predict near term risks of recessions”. The blue GDP distribution is centred around the Q2 2019 GDP forecasts reflected in the September 2018 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. The yellow GDP distribution is centred around the Q4 2019 GDP forecasts reflected in the March 2019 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area.

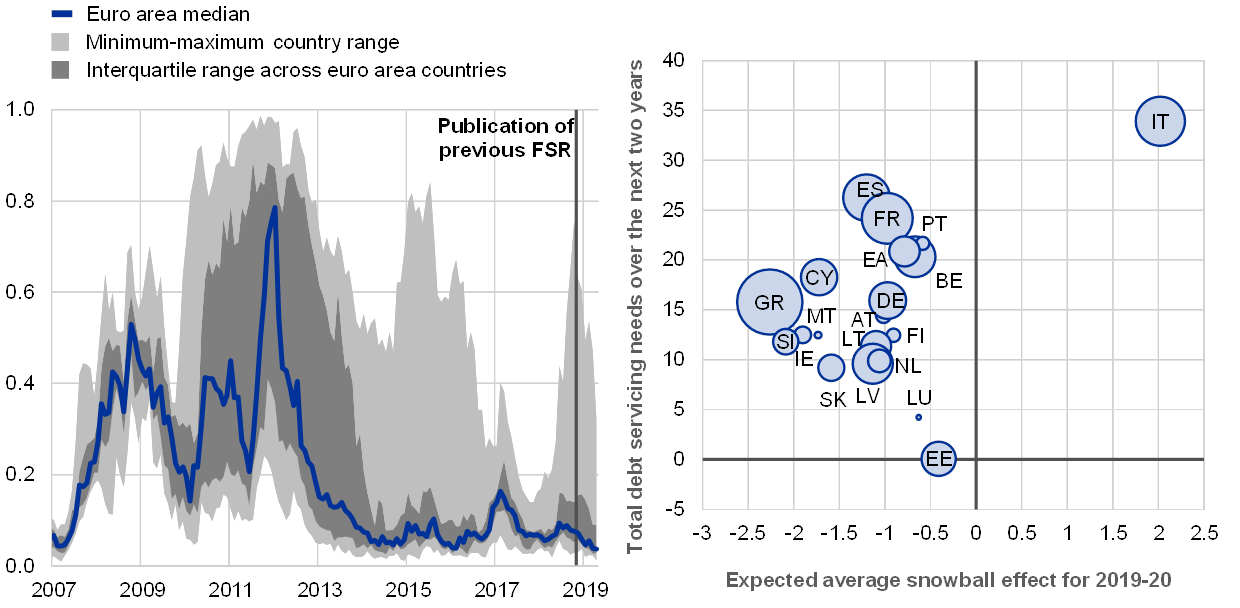

A materialisation of downside risks to the growth outlook would intensify public debt sustainability challenges

A prolonged period of low growth may unearth debt sustainability concerns. Although the aggregate stock of public debt in the euro area has fallen somewhat since the peak of 2014 (standing at around 87% of GDP in 2018), the stock has continued to increase in some of the highly indebted countries. Should downside risks to growth materialise, financing costs for vulnerable sovereigns are likely to increase and may unearth debt sustainability concerns. In addition to the high level of debt and large fiscal deficits, some countries could face rollover risks if market participants reassess sovereign risk (see Chart 2, right panel). A sound medium-term approach to public finances, as expected under the Stability and Growth Pact, is key to containing public financing costs, which would support debt sustainability.

Chart 2

Country-specific debt sustainability concerns remain present

Composite indicator of systemic stress in sovereign bond markets (left panel); average interest rate-growth differential for 2019-20 versus total debt servicing needs over the next two years (right panel)

(left panel: Jan. 2007-Apr. 2019; right panel: percentage of GDP, the size of the bubbles represents the degree of political instability based on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators)

Sources: European Commission (AMECO database), ECB (Government Finance Statistics), World Bank and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the SovCISS shown is available for the euro area as a whole and for 11 euro area countries. The methodology of the SovCISS is described in Garcia-de-Andoain, C. and Kremer, M., “Beyond spreads: measuring sovereign market stress in the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2185, ECB, October 2018. Right panel: data on government debt service over the next two years only reflect existing maturing securities (principal and interest). The snowball effect refers to the difference between sovereign funding costs and expected GDP.

Recently, stress in euro area sovereign bond markets has been limited and country-specific. Most sovereign bond spreads relative to risk-free rates have been broadly stable since November 2018. Upward pressure on sovereign spreads stemming from the weakening growth outlook has been counterbalanced by the continued accommodative monetary policy of the ECB. The composite indicator of systemic stress in euro area sovereign bond markets (SovCISS) suggests that financial markets see no imminent debt sustainability concerns for the euro area as a whole (see Chart 2, left panel). However, country dispersion remains high.

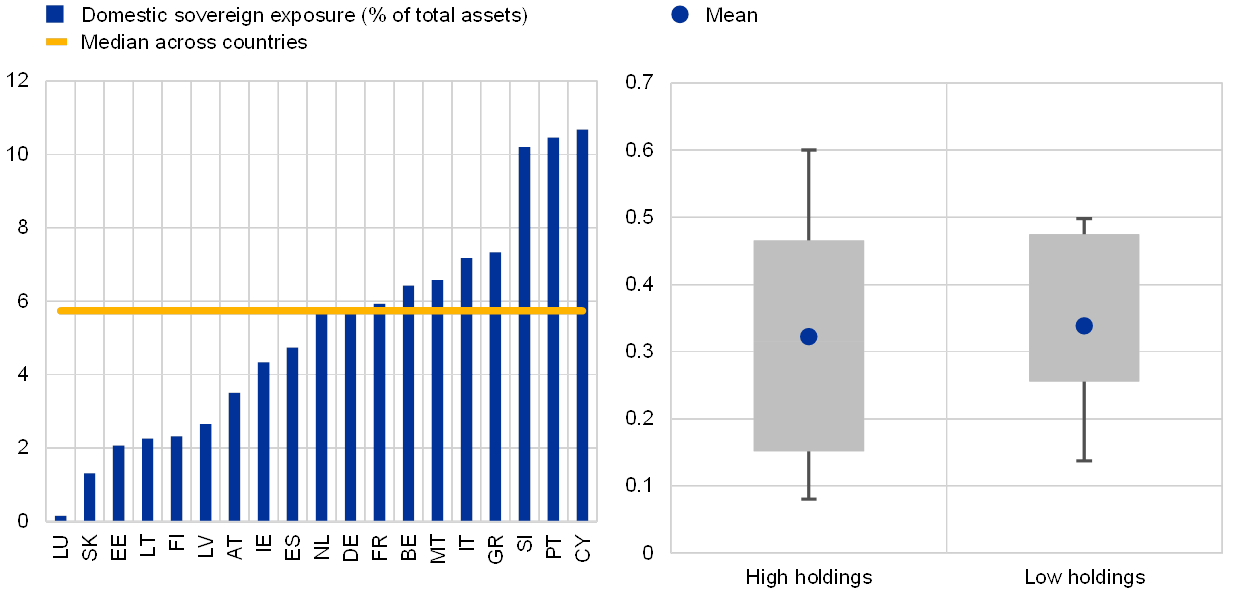

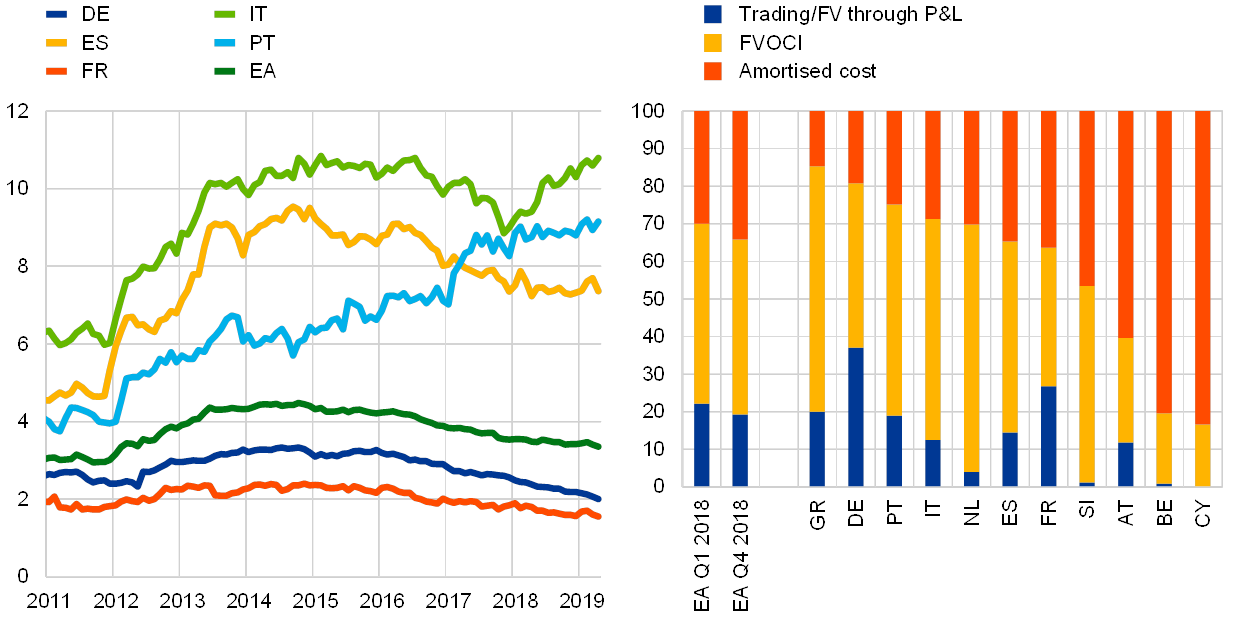

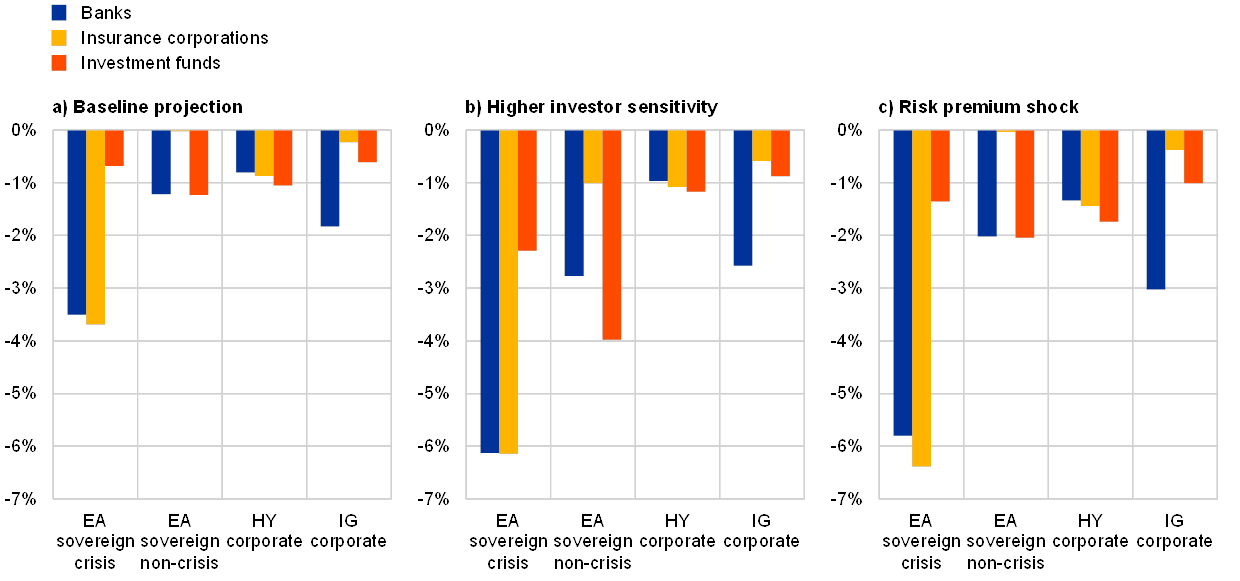

Renewed market concerns in sovereign bond markets could potentially have repercussions for the financial system and broader economy. A sharp increase in sovereign bond spreads could have an adverse impact on banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions with elevated levels of sovereign bond exposure (through the mark-to-market impact on banks’ capital and income statements and higher market-based funding costs) (see Chart 3, left panel). While banks with larger domestic sovereign exposures do not seem to face closer credit default swap (CDS) spread correlations with their sovereign than their peers with smaller exposures (see Chart 3, right panel), it is likely that all domestic exposures would be affected by the deterioration in macroeconomic conditions triggered by sovereign stress. To alleviate some of these vulnerabilities, banks and other financial firms with high domestic exposures are encouraged to increase the geographical diversification of their assets.

Chart 3

Some euro area banks might benefit from diversifying beyond domestic markets

Euro area banks’ exposure to the domestic sovereign (left panel); correlations between bank and sovereign CDS spreads for banks with low and high sovereign bond holdings (right panel)

(left panel: Q4 2018, percentages; right panel: Jan. 2008-Mar. 2019, mean, 10th and 90th percentiles and interquartile ranges)

Sources: ECB supervisory data, ECB balance sheet item data and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: sample consists of euro area significant institutions at the highest level of consolidation. The exposures cover sovereign bonds and loans to sovereigns fulfilling the requirement of the counterparty being part of the general government sector, i.e. central governments, state or regional governments, and local governments, including administrative bodies and non-commercial undertakings, but excluding public companies and private companies held by these administrations that have a commercial activity; social security funds; and international organisations, such as institutions of the European Union, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements (Articles 112 and 147 of the Capital Requirements Regulation). Deposits with central banks are excluded. Right panel: sample consists of euro area monetary financial institutions (unconsolidated data). The low/high holdings refer to below and above-median holdings in the sample.

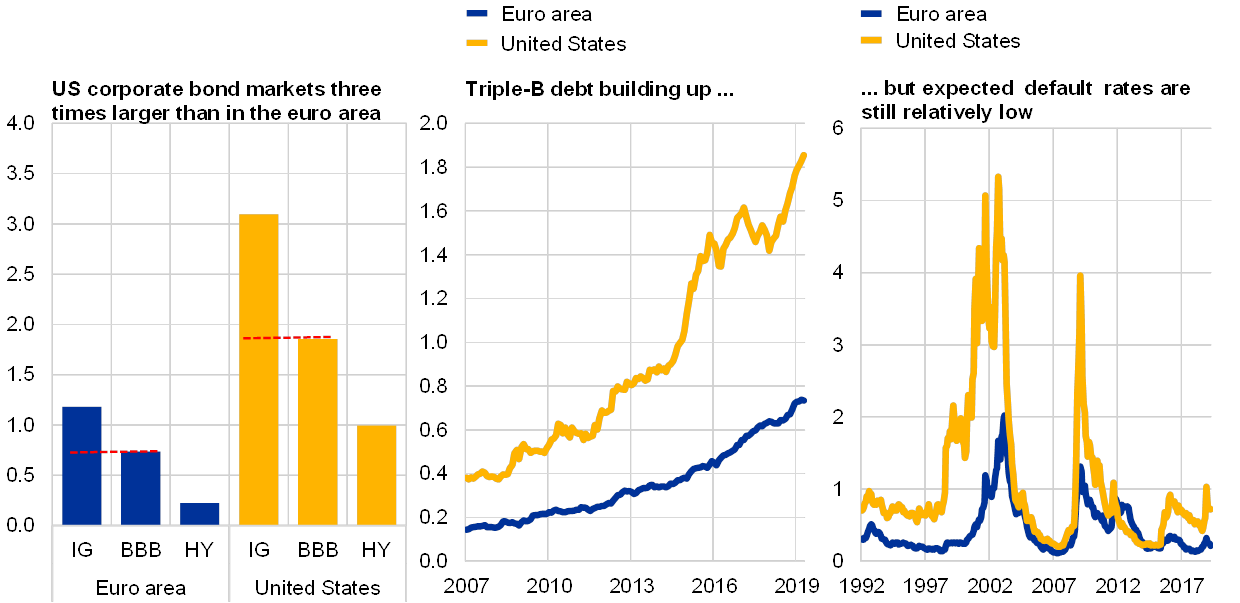

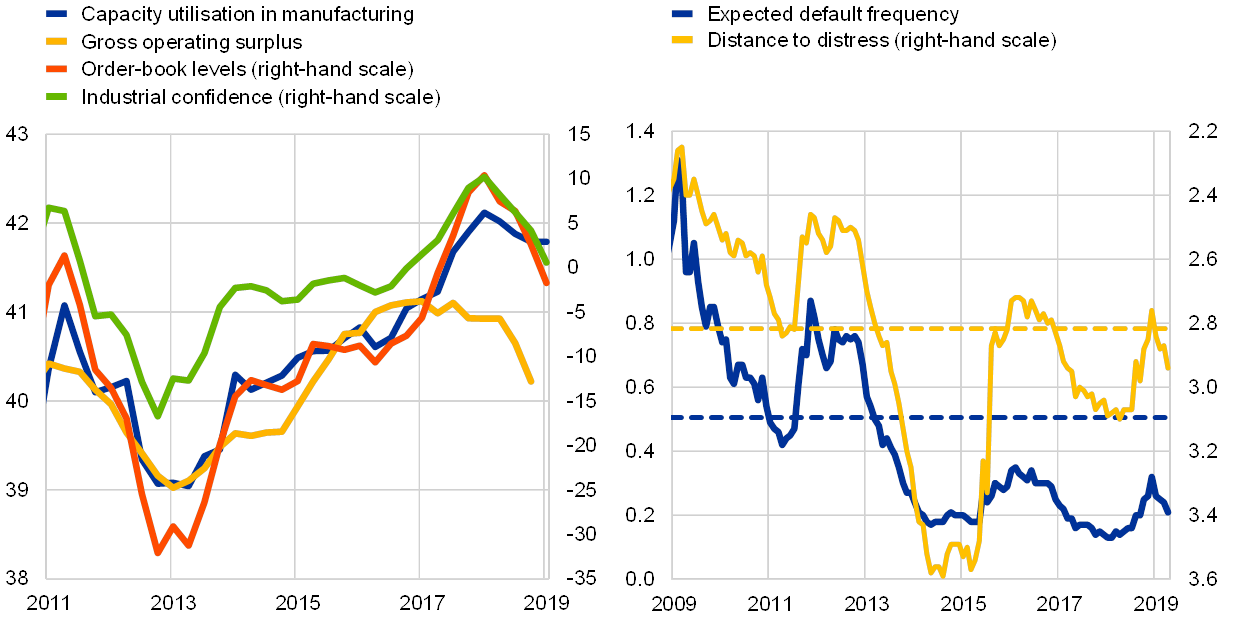

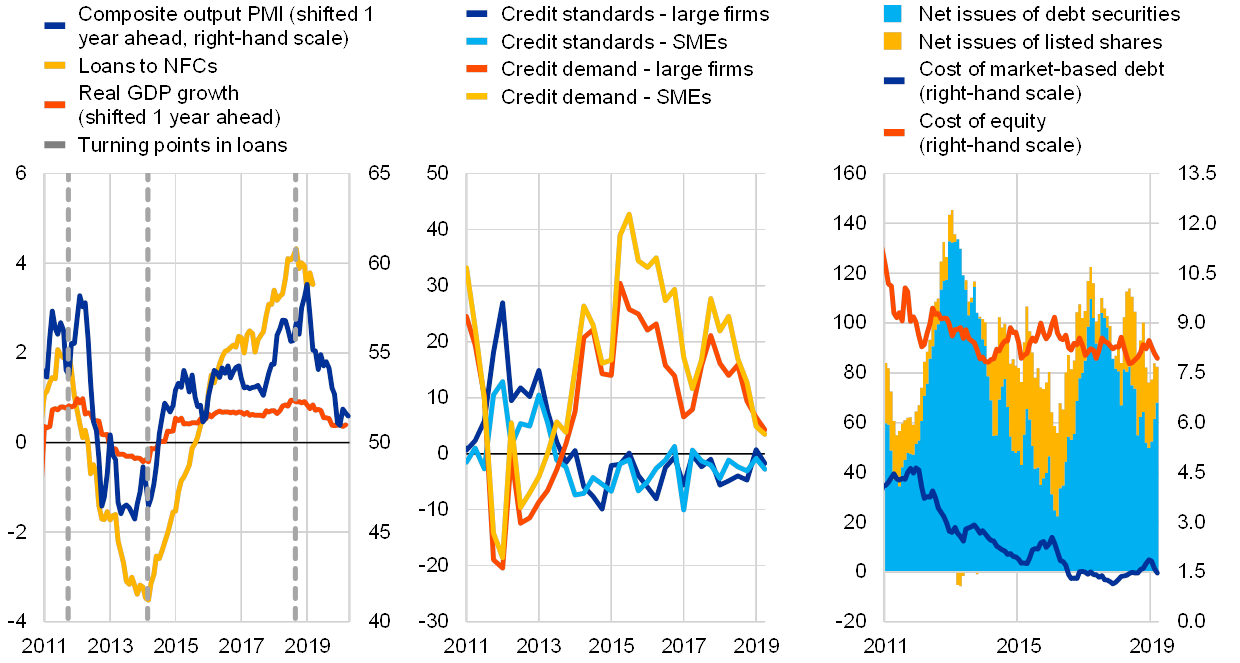

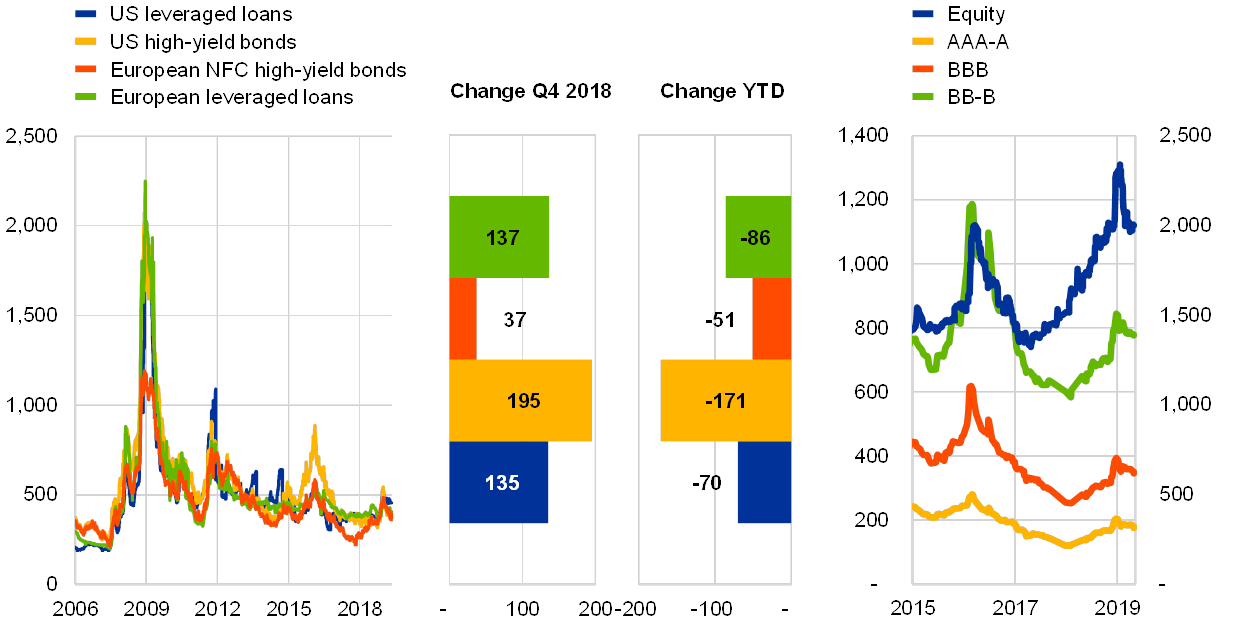

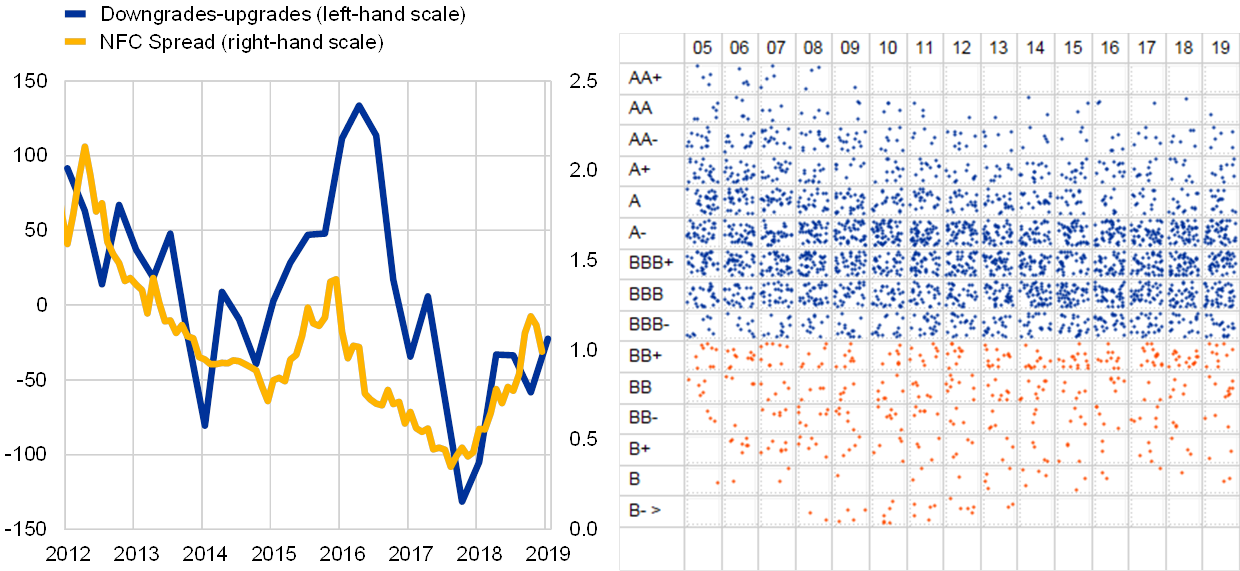

Signs of vulnerability in corporate credit markets

The low interest rate environment of recent years has contributed to a build-up of vulnerabilities in some segments of the euro area corporate sector. Generally, low corporate interest payment burdens, high liquidity buffers and a relatively diversified financing structure alleviate near-term financial stability risks for the euro area corporate sector. But the favourable financing conditions in most advanced economies have also allowed firms with weaker balance sheets to increase their leverage. For example, the share of issuance by firms rated one notch above non-investment-grade has increased rapidly across the globe and the euro area BBB markets have doubled in size over the past five years (see Chart 4, left and middle panels). This trend partly reflects a diversification of firms’ financing sources. In fact, market-based funding sources have gained in importance in recent years, thereby improving the resilience of corporate financing to shocks stemming from the banking sector. Expected default rates have increased slightly in recent quarters, but remain low overall (see Chart 4, right panel). A sharp deterioration of the growth outlook could lead to a turn in the global credit cycle. There is a particular risk that companies on the edge of the investment-grade spectrum may face refinancing challenges if they were to be downgraded to the high-yield segment.

Chart 4

The size of the lower-rated non-financial corporate bond market has increased, as expected default rates remain low

Size of the euro area and the US non-financial corporate bond markets (left panel); euro area and US non-financial BBB-rated corporate debt (middle panel); expected default rates for European and US non-financial corporates (right panel)

(left panel: April 2019, € trillions; middle panel: Jan. 2007-Apr. 2019, € trillions; right panel: Jan. 1992-Apr. 2019, annual percentages)

Sources: Bloomberg, Barclays Live, Moody’s KMV and ECB calculations.

Notes: IG refers to investment-grade bonds and HY to high-yield bonds. The outstanding amounts in the left and middle panels refer to bonds denominated in euro for the euro area and US dollars for the United States.

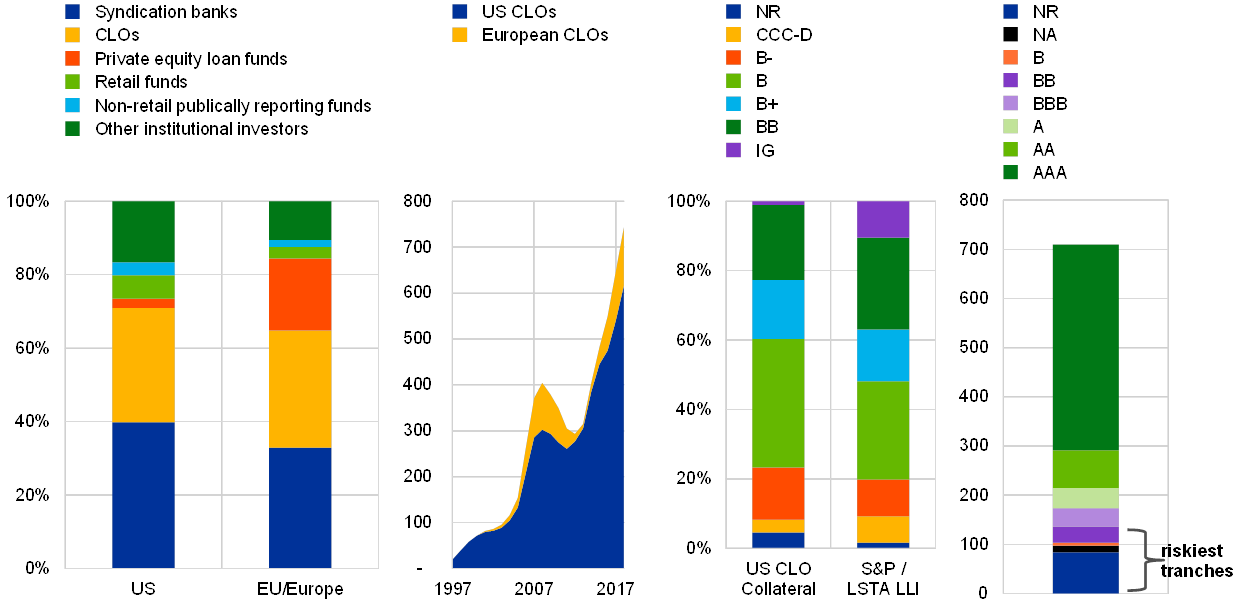

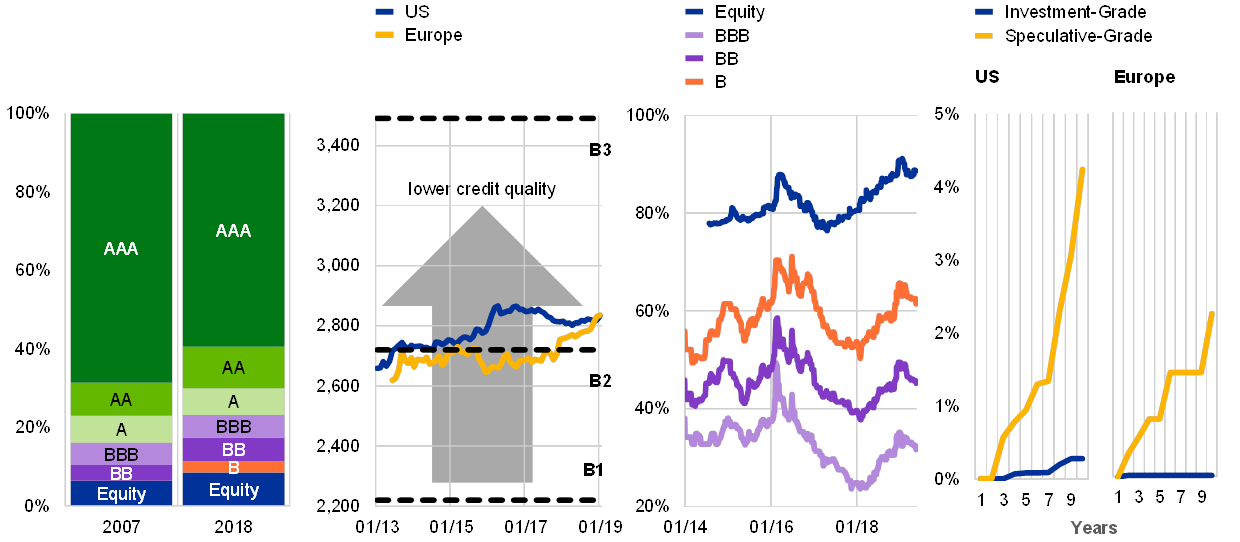

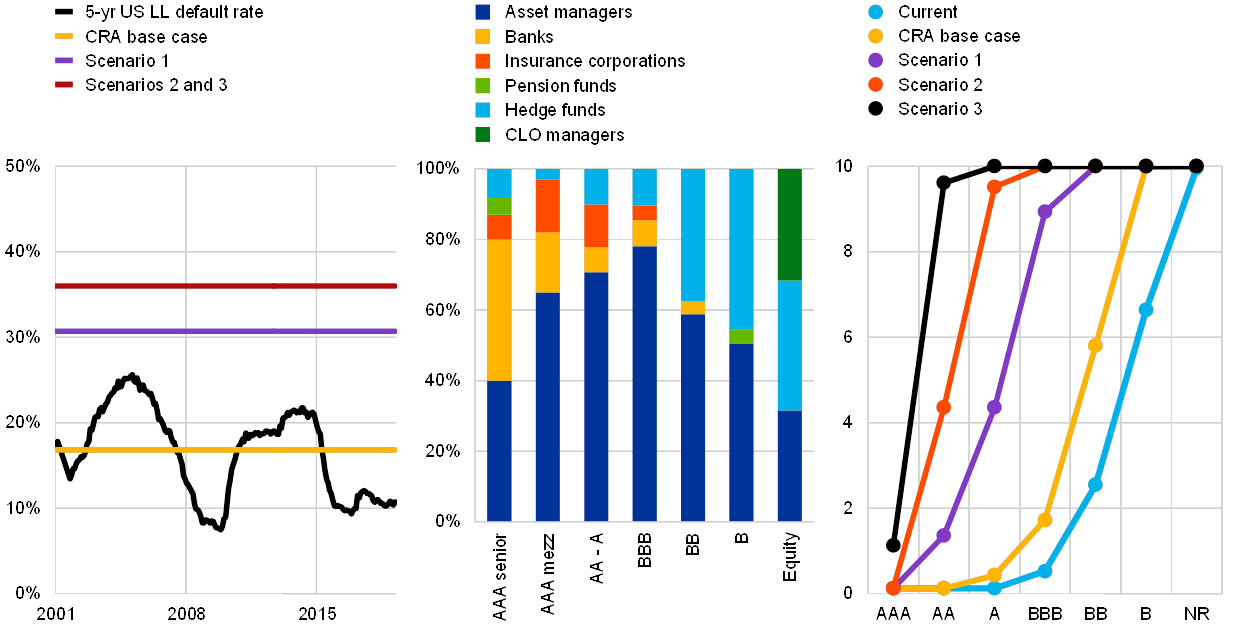

Risk-taking is particularly pronounced in higher risk segments, such as the leveraged loan markets. Weak underwriting standards have become commonplace in the US and European leveraged loan markets (see Chapter 2). This trend entails two broad risks. First, it may keep very weak firms alive for longer. Second, deteriorating underwriting standards may also generate lower future recoveries (compared with the past) in the event of defaults. That said, in the euro area, the share of leveraged debt issued by firms (the sum of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds) is around 8% (net of inter-company loans and trade credit), which is not particularly high.

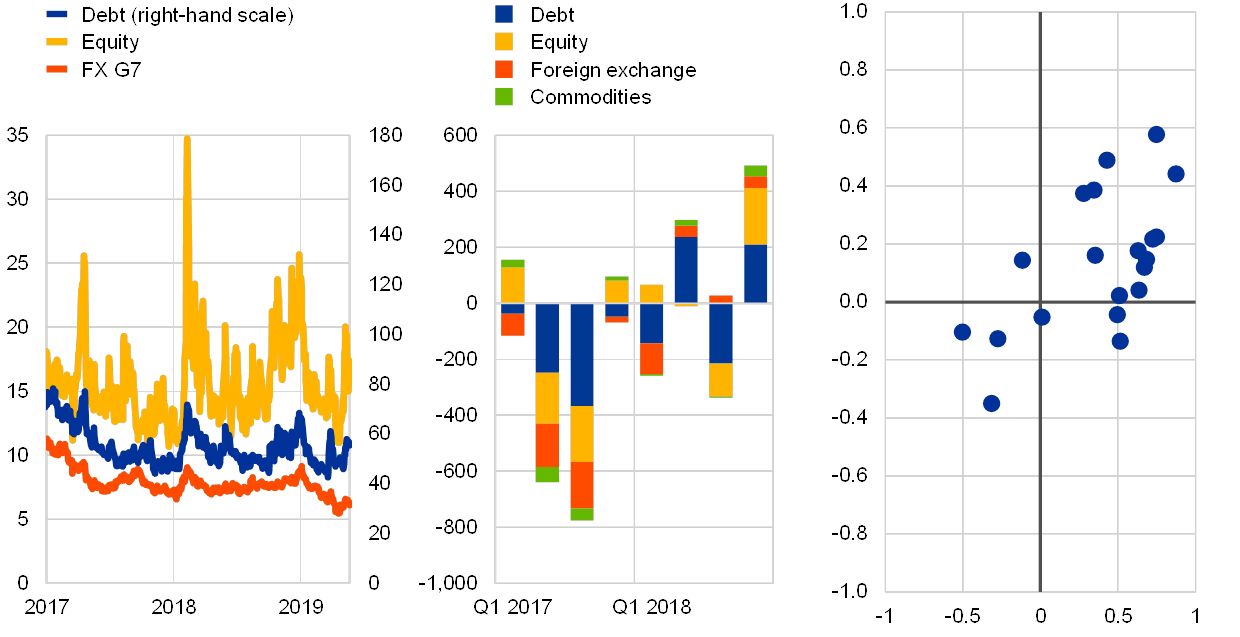

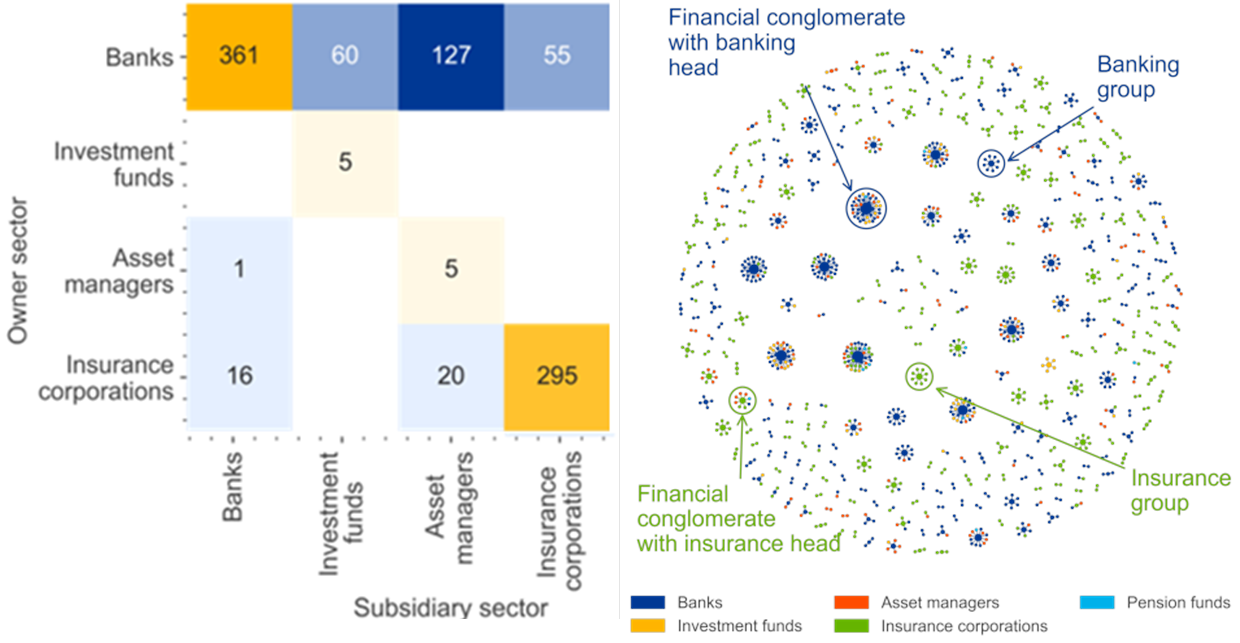

Search for yield, liquidity risk and leverage in the non-bank financial sector could amplify the wider financial cycle

Investment funds appear to be the sector most directly exposed to corporate risk. In search of higher yields, euro area funds and insurers have increased their exposures to BBB-rated and high-yield bonds over the last five years (see Chapter 4). Accordingly, BBB bonds now represent a large and increasing part of non-banks’ holdings of non-financial corporate bonds, i.e. 40% for insurance corporations and pension funds and 35% for investment funds as at end-2018, compared with 33% and 31% as at end-2013, respectively. Furthermore, euro area asset managers and investment funds are among the main holders of low-rated collateralised loan obligations (see Box 4). In the event of an economic downturn or a sudden correction in risk premia, these often highly leveraged companies could face difficulties in servicing their debt, with possible downgrades to high-yield bonds. This may, in turn, amplify the effects of the downturn through higher borrowing costs and default rates.

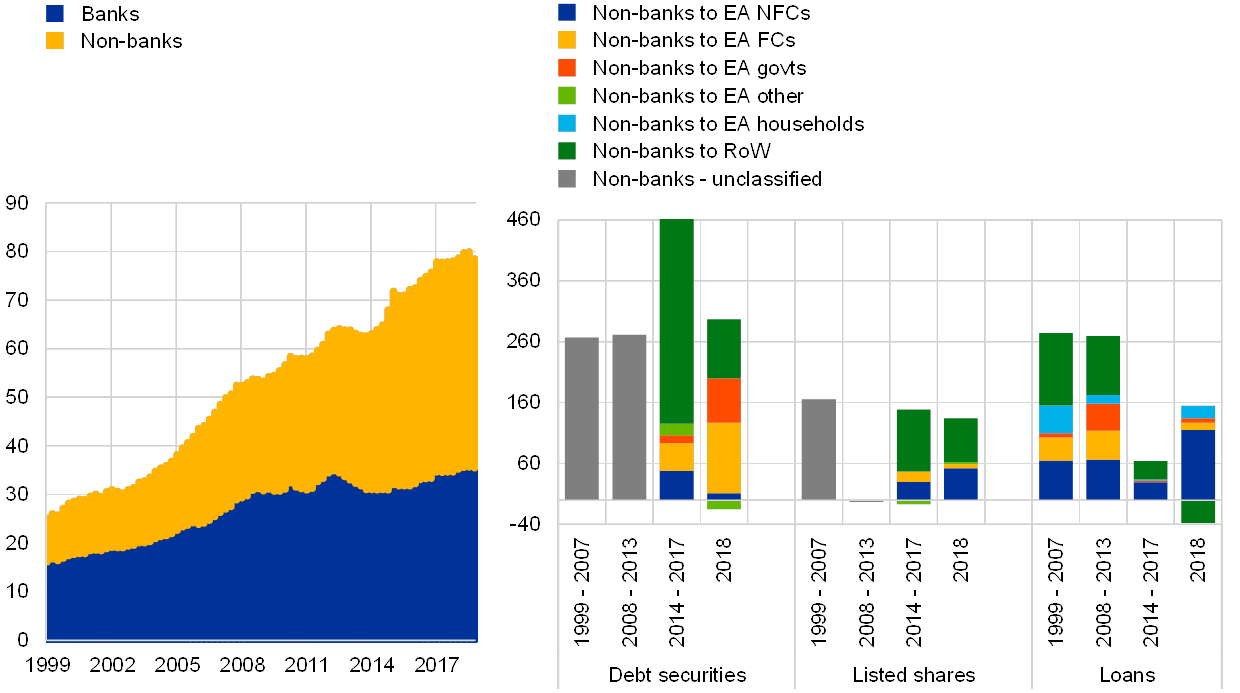

A growing role for euro area non-banks in real economy financing went hand in hand with an increase in risk exposure and a growing financial market footprint of these firms. A shift of real economy financing away from banks towards market-based funding has continued. While this helps diversify the funding sources for the real economy, two risks result. First, much of the implied financing activity has been concentrated in the lower part of the credit quality spectrum, amid high indebtedness in some segments of the corporate and government sectors. Second, non-banks may amplify the cyclical underpricing of risk as they search for yield, potentially also taking on more leverage and liquidity transformation. Should these risks unwind in a disorderly manner, this could lead to a drying-up of funding flows and affect the funding conditions of the real economy more broadly.

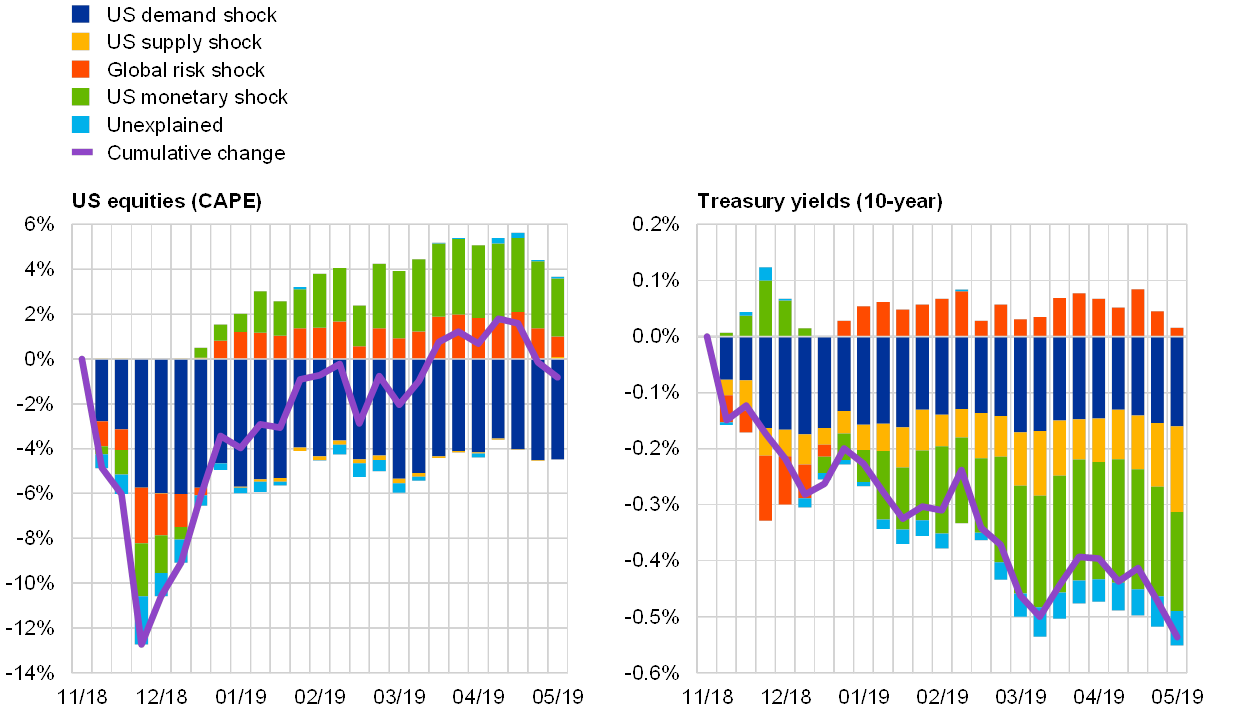

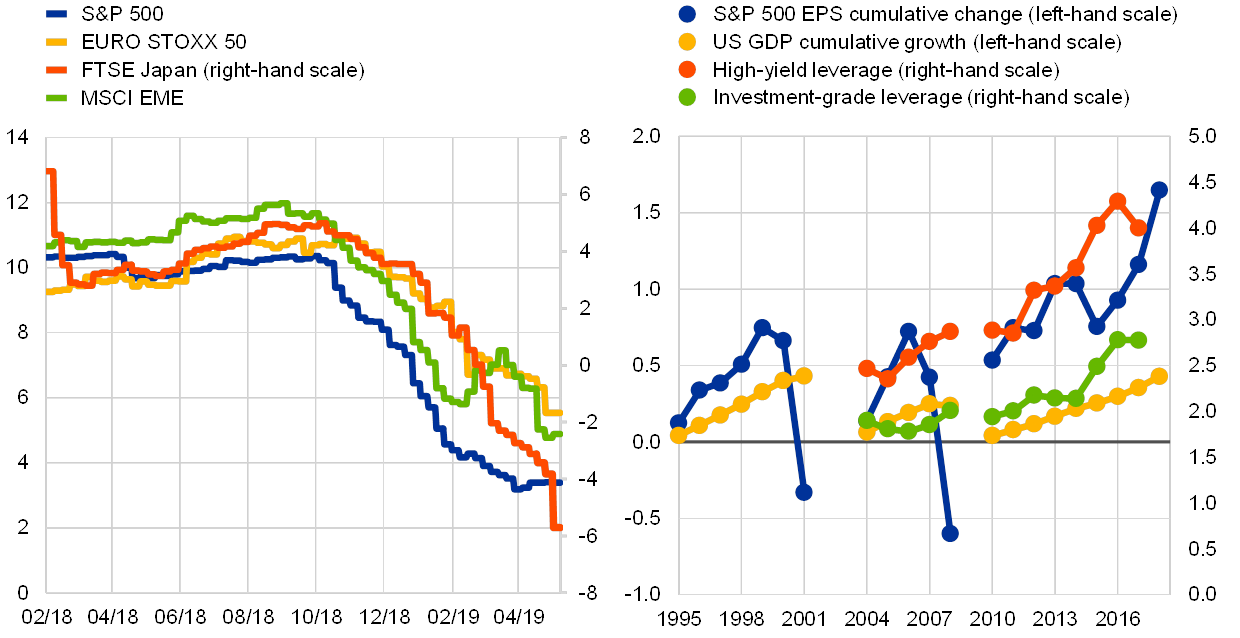

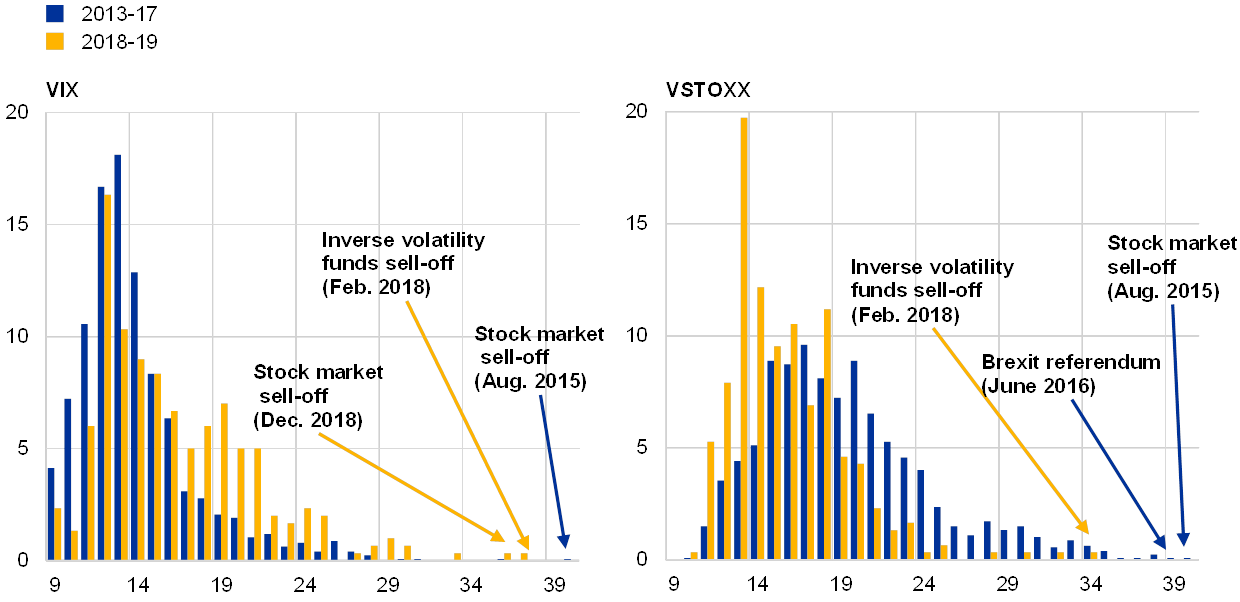

Potential for asset price corrections and an unwinding of the considerable investment fund inflows over the last decade

Greater economic and policy uncertainty has contributed to bouts of high volatility in financial markets. In December last year, global stock markets and the riskier parts of the corporate bond markets sold off sharply after a prolonged period of rising asset prices. Concerns about the economic cycle and – in some cases – high valuations triggered the corrections. While the December turmoil was orderly and without immediate widespread consequences, the episode illustrated that investor sentiment can prove unpredictable. In the first four months of 2019 market sentiment improved and the financial assets affected by the turmoil recovered most or all of the earlier losses. The greater risk appetite in financial markets was partly attributed to central bank communication assuring market participants of a continued accommodative stance. More recently, concerns about escalating trade sanctions between the United States and China once again prompted declines in equity and corporate bond prices, as risk premia increased.

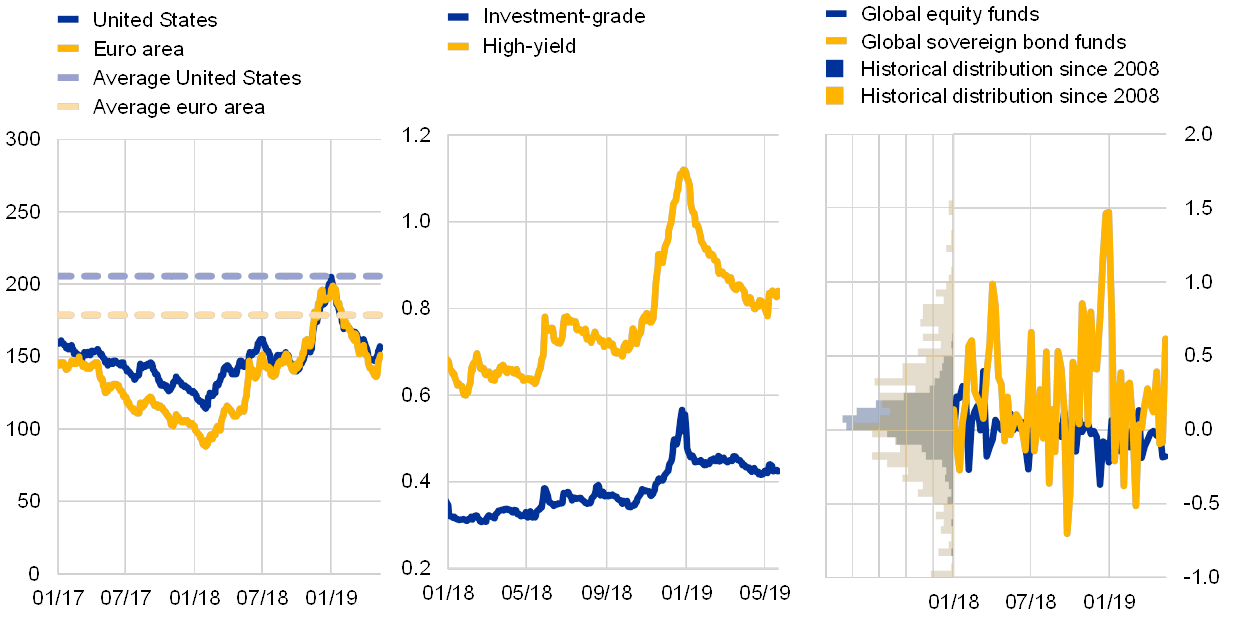

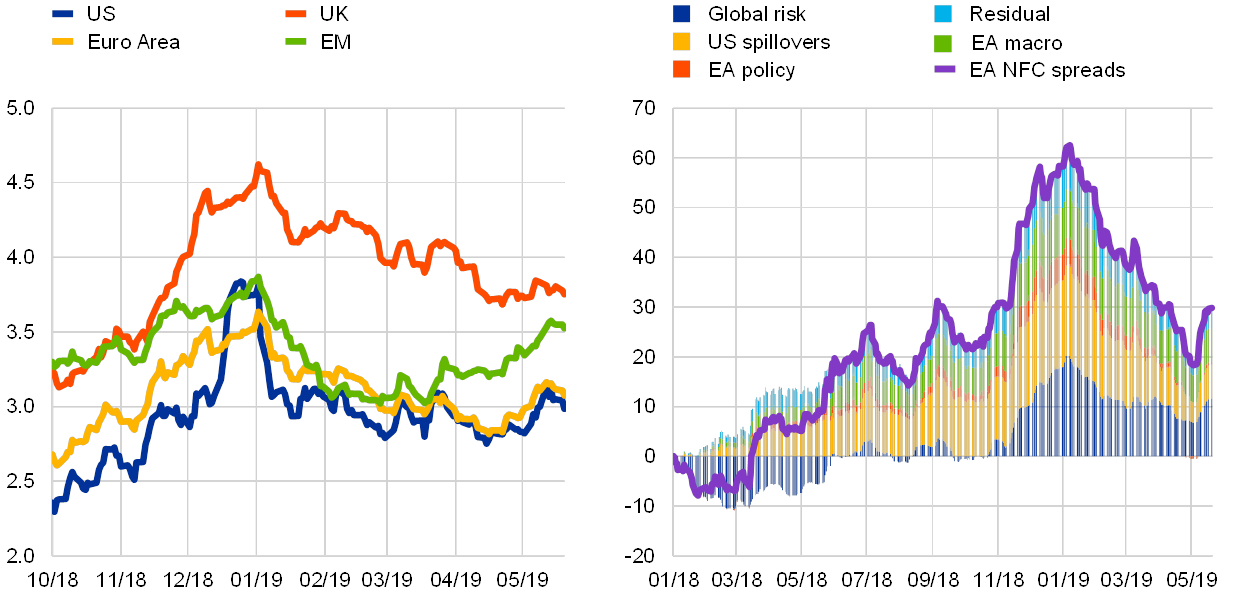

Chart 5

Compressed corporate bond spreads amid fragile liquidity conditions and volatile investment flows

US and euro area BBB spread (left panel); bid-ask spreads of euro area investment-grade and high-yield non-financial corporate bonds (middle panel); net flows into equity and sovereign bond funds as a percentage of assets under management (right panel)

(left panel: Jan. 2017-May 2019, basis points; middle panel: Jan. 2018-May 2019, percentage of mid-price; right panel: Jan. 2018-May 2019, percentages, historical distributions since 2008)

Sources: Bloomberg, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, iBoxx, Thomson Reuters Datastream, EPFR and ECB calculations.

Note: Left panel: the dashed lines show the long-term averages since January 2002.

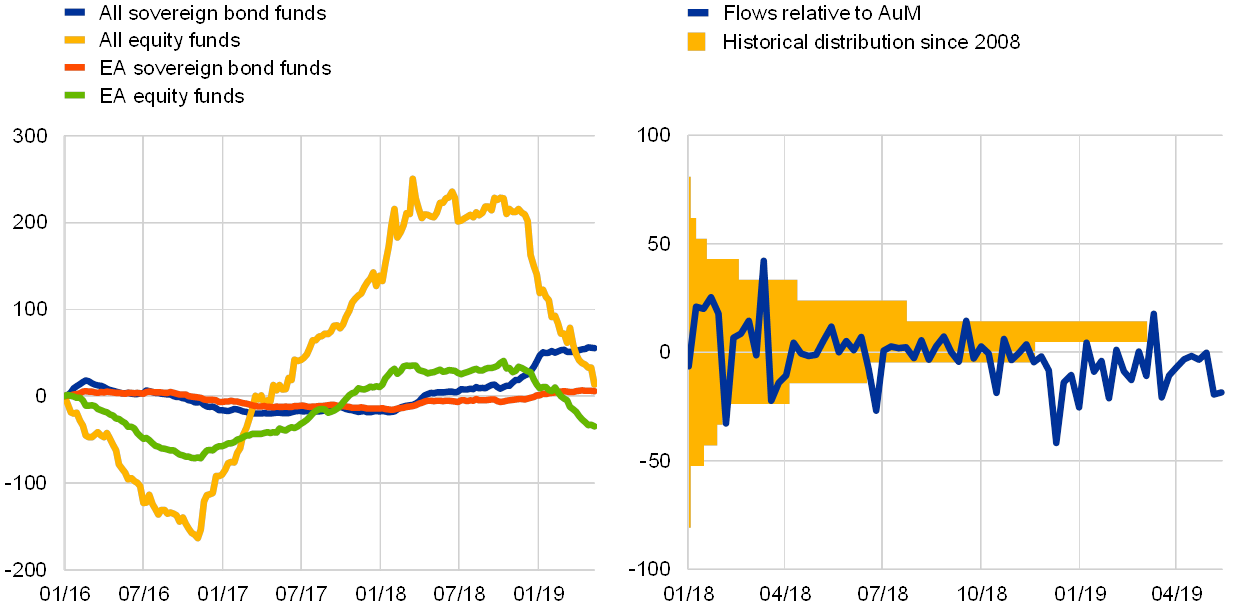

High valuations in some asset classes may trigger future market corrections. The favourable market sentiment in early 2019 highlighted an increasing divergence between financial markets and the deteriorating economic growth prospects. For some asset classes, prices seem detached from their underlying fundamentals. For example, based on the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio, US equity prices look stretched and may be subject to further adjustment. Furthermore, compressed corporate bond spreads in some advanced economies leave room for rapid corrections (see Chart 5, left panel).

Low market liquidity and unpredictable investor behaviour could amplify any further volatility in markets. The December turmoil showed that market liquidity can dry up quickly in periods of stress. In the euro area corporate bond markets, liquidity conditions remain fragile despite the recovery in bond prices in 2019 (see Chart 5, middle panel). Furthermore, rapid portfolio reallocations could augment future asset price corrections. During the December turmoil, portfolio shifts from equity funds and riskier corporate bond funds to government bond funds were unusually large compared with similar episodes in the past (see Chart 5, right panel).

A sudden and abrupt repricing of financial assets could trigger fund outflows, possibly resulting in forced asset sales amplifying stress in less liquid markets. Overall, the investment fund sector seems to have coped well with outflows during the high volatility episode in December 2018. At the same time, liquidity and credit risks are still high in some parts of the sector and pockets of high leverage may build up in the alternative investment fund sector (see Chapter 4). A sudden and abrupt repricing of risk could lead to forced asset sales. Such sales have the potential to amplify the original shock to asset prices in less liquid markets.

Property prices could correct if downside risks to growth were to materialise

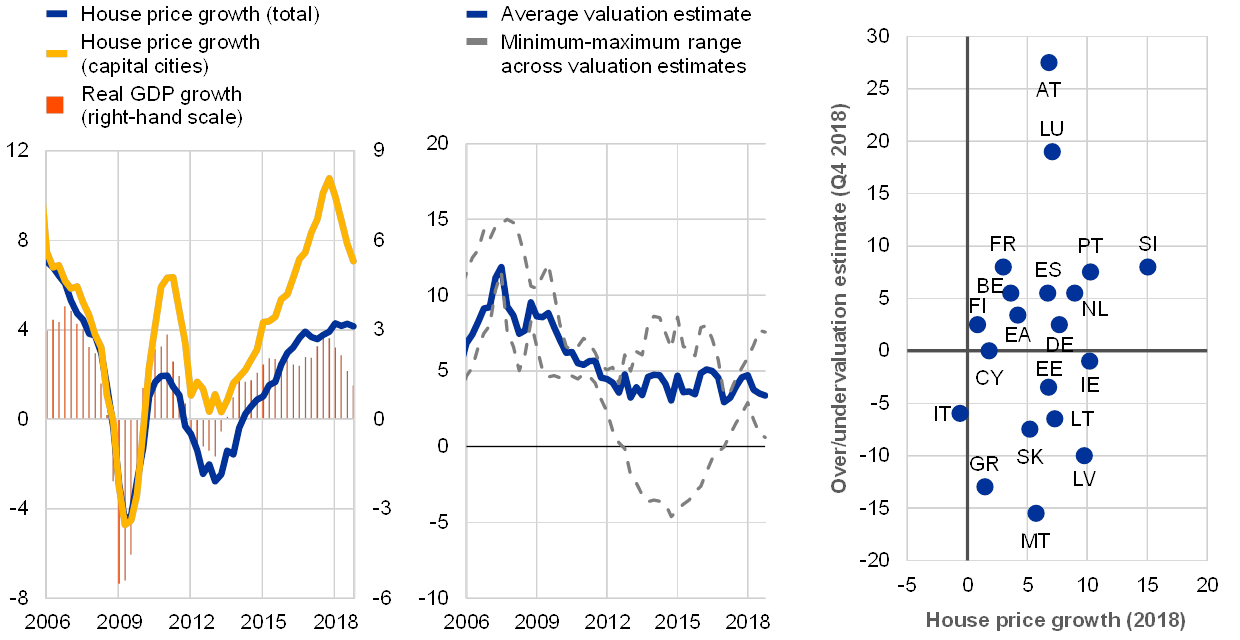

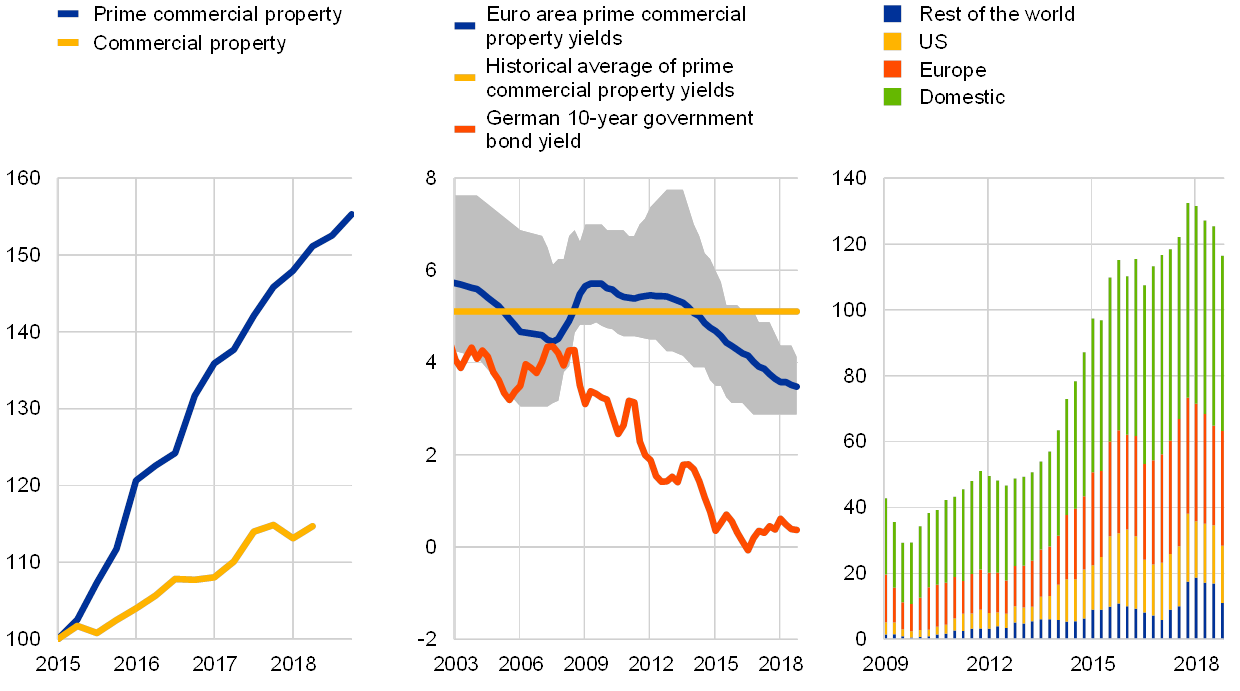

Real estate prices in the euro area have continued to rise despite the more challenging macroeconomic outlook. House prices in the euro area grew by 4.2% in 2018, contributing to signs of mild overvaluation for the euro area as a whole. Moreover, the post-crisis decline in household indebtedness appears to have slowed down significantly.

In commercial real estate markets, price and transaction volume trends also remain strong, with signs of stretched valuations in particular in prime segments. However, the price and transaction volume dynamics decelerated somewhat in recent quarters compared with the peak levels observed in 2016 and 2017. The high share of non-euro area transaction inflows contributes to the vulnerability of commercial real estate markets. A potential change in global financial conditions resulting in a relative shift of returns in euro area and non-euro area markets might result in outflows from commercial real estate by international investors, which have played a crucial role in driving market activity in recent years.

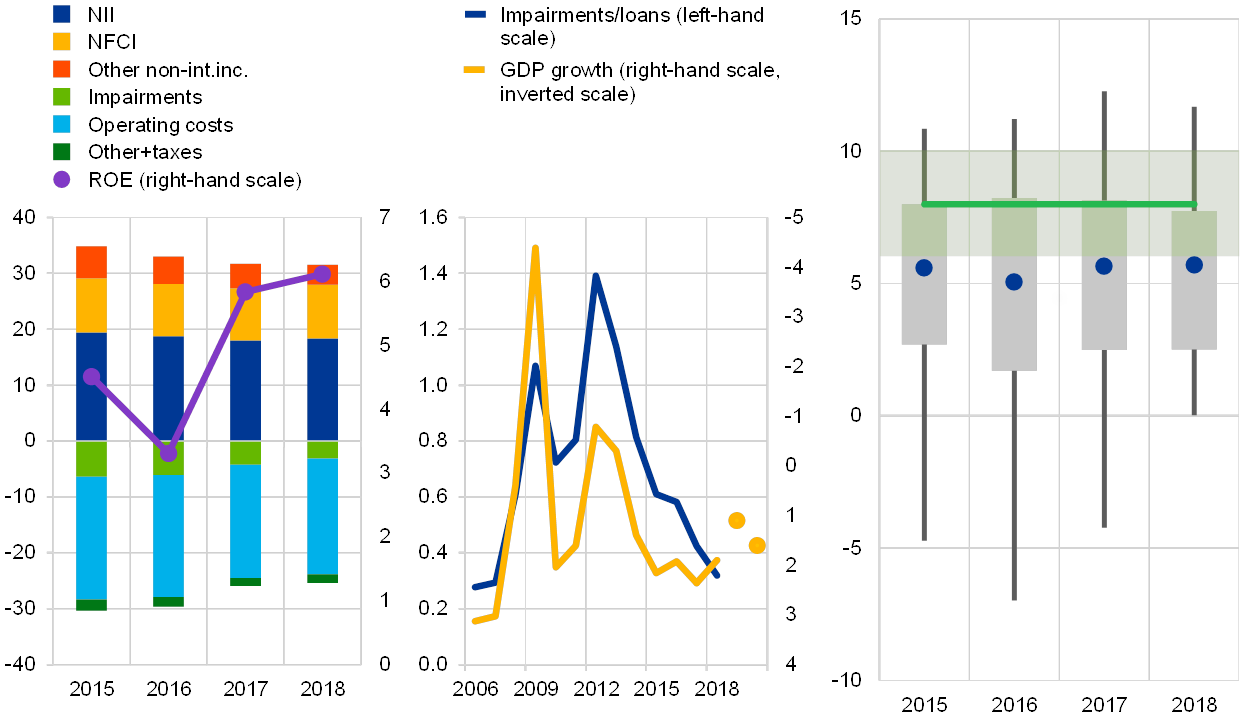

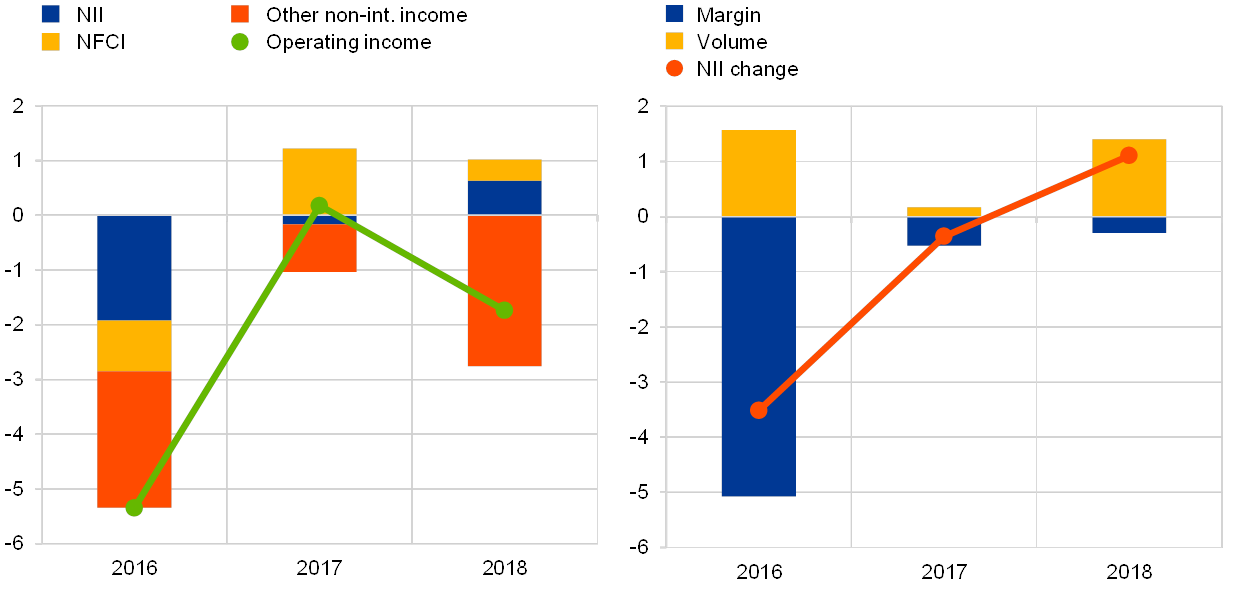

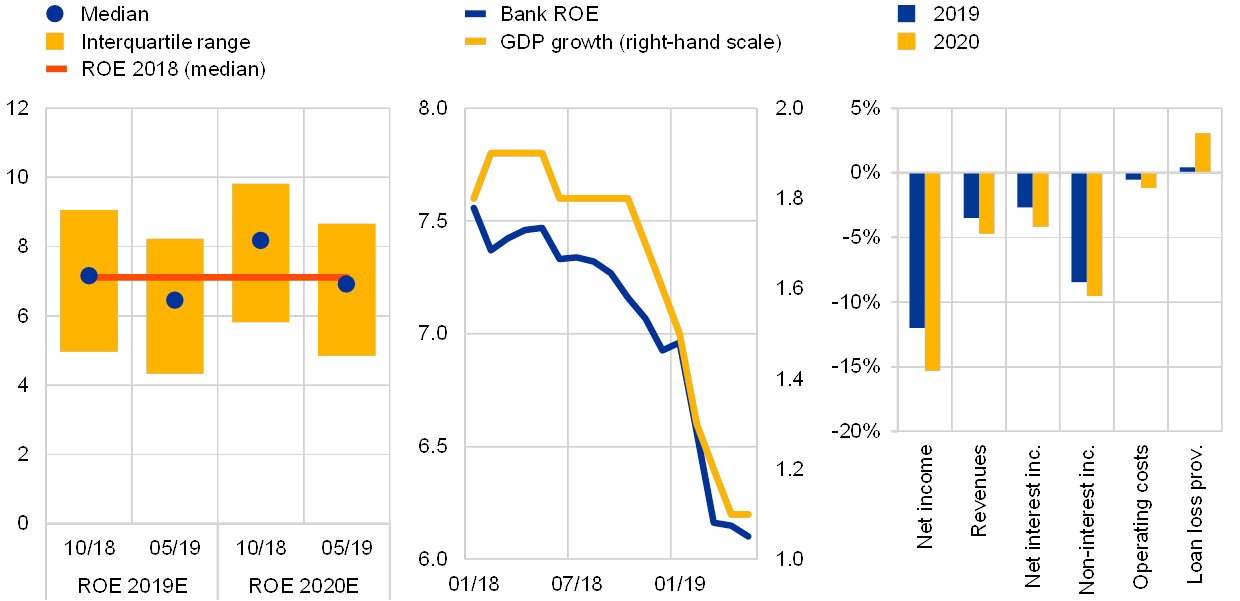

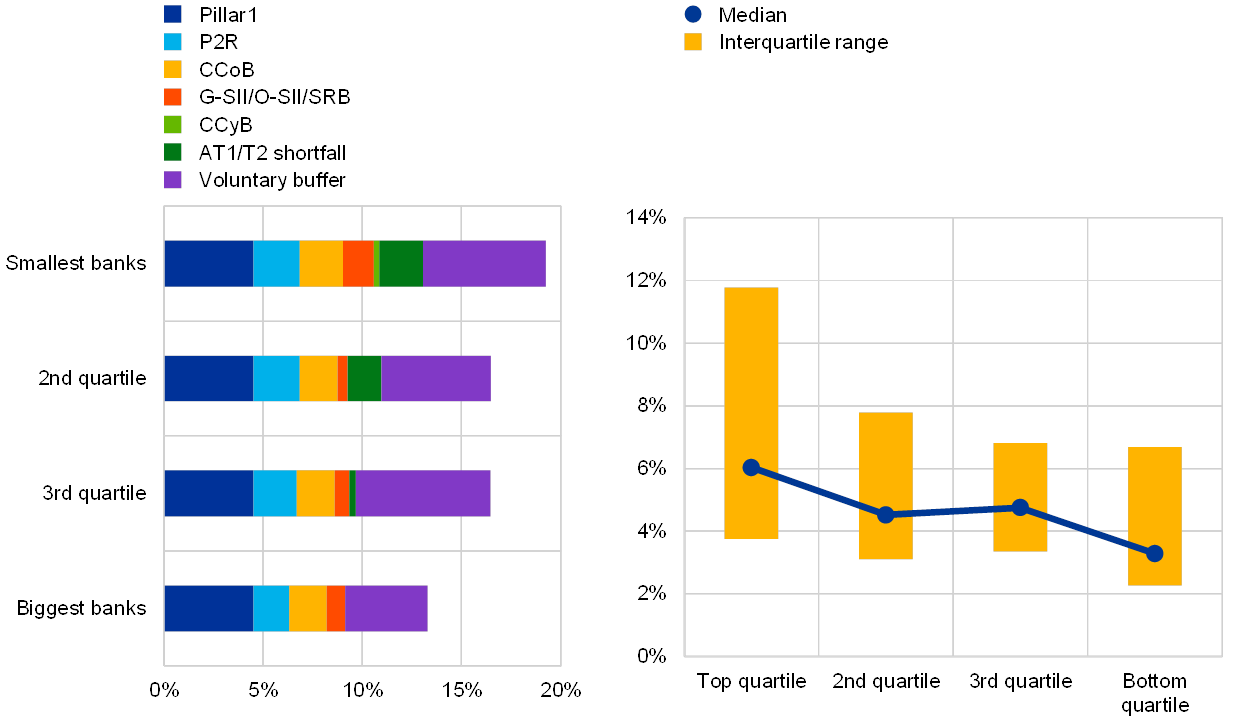

Structural profitability challenges for the euro area banking sector

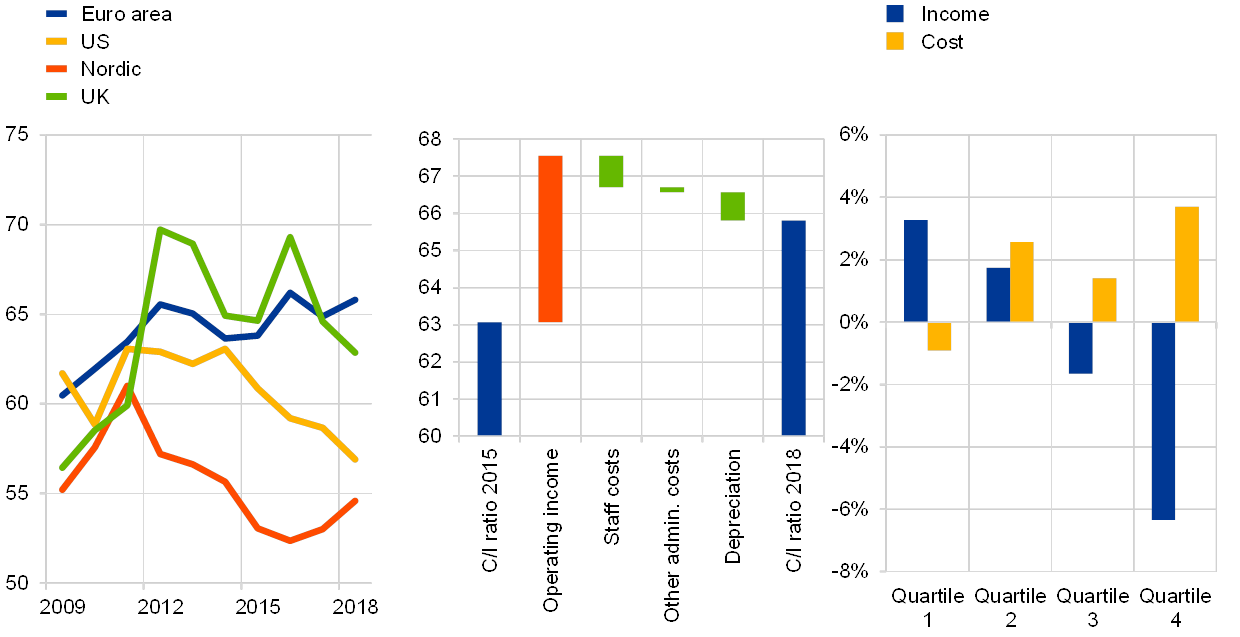

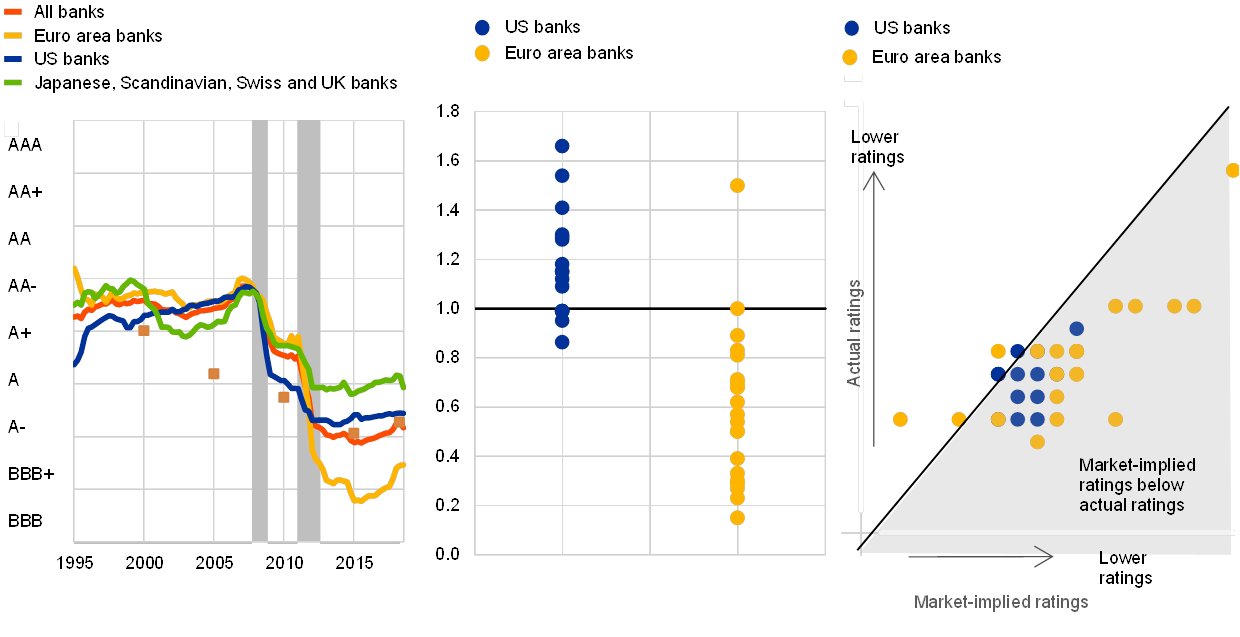

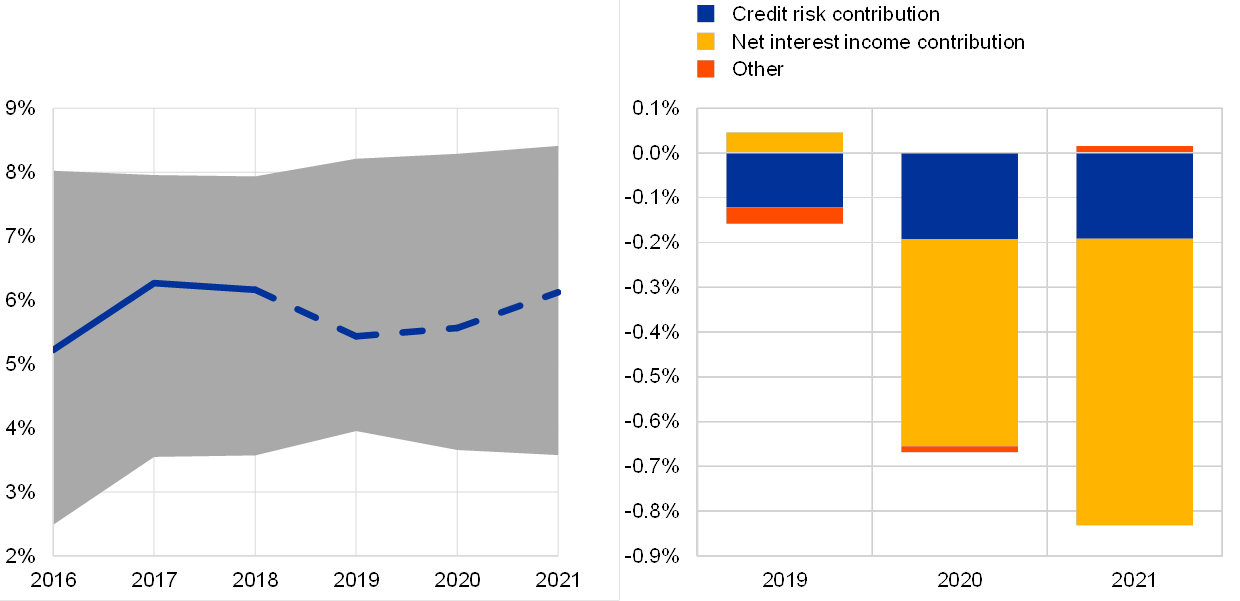

The prospect of weaker economic growth has weighed further on structurally weak profitability expectations for euro area banks. The return on equity for euro area banks stood at around 6% in 2018, broadly unchanged from a year earlier (see Chart 6, left panel). Profitability continues to fall short of the returns required by investors for the majority of euro area banks. The cost of equity for most of the largest listed European banks is estimated to lie in the range 8-10%.[1] Consistent with a situation in which the cost of equity is higher than the return on equity, most euro area banks are trading at price-to-book ratios that are lower than those of their international peers. The low growth and interest rate environment could further dent profitability stemming from the maturity transformation business – not least as retail household deposit interest rates tend to be bound at zero.[2] That said, subdued bank profitability mainly stems from structural challenges in the form of low cost-efficiency, limited revenue diversification and high stocks of legacy assets in some jurisdictions. Near-term profitability forecasts provided by market analysts have been revised down in recent quarters, which can probably be attributed to the slowdown in economic growth (see Chapter 3). Furthermore, a comparison with other major economies reveals that euro area banks’ creditworthiness lags behind that of their main global competitors (see Chart 6, right panel).

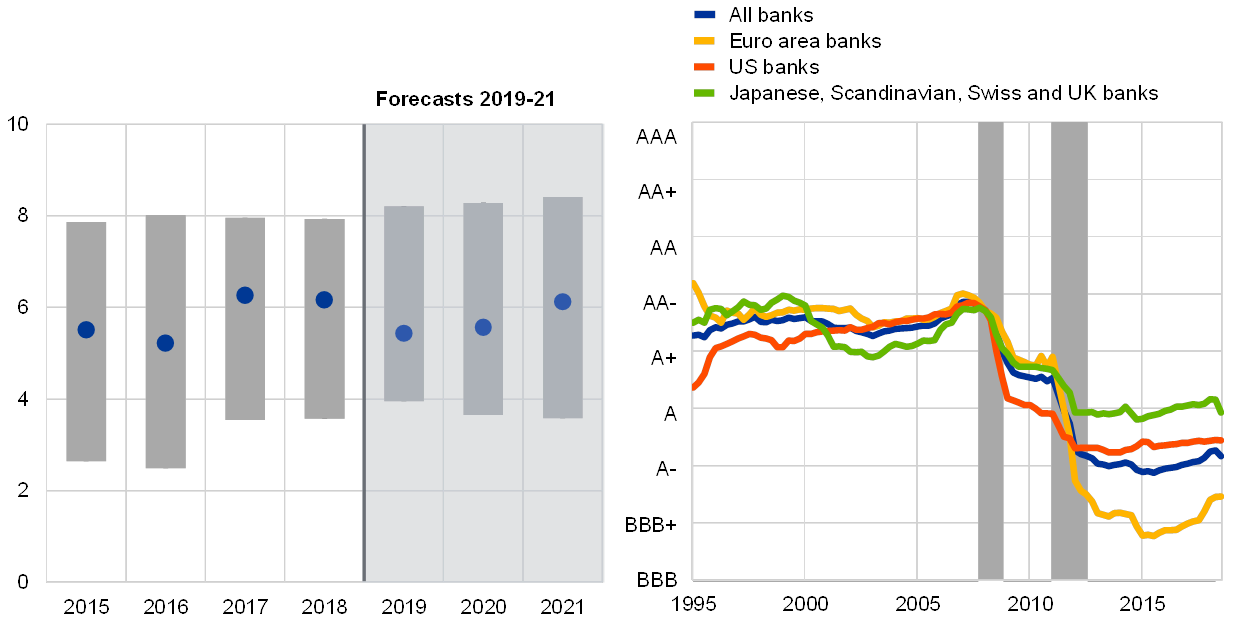

Chart 6

Subdued profitability outlook and creditworthiness of euro area banks persistently below that of their international peers

Euro area banks’ actual (2015-18) and expected (2019-21) return on equity (left panel); median ratings for large global listed banks (right panel)

(left panel: 2015-21, annual percentages, median and interquartile range; right panel: Jan. 1995-Mar. 2019)

Sources: ECB, Standard & Poor's, Moody's, Fitch Group, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the sample consists of euro area significant institutions. Right panel: the grey shaded areas represent periods of euro area recessions as defined by the CEPR.

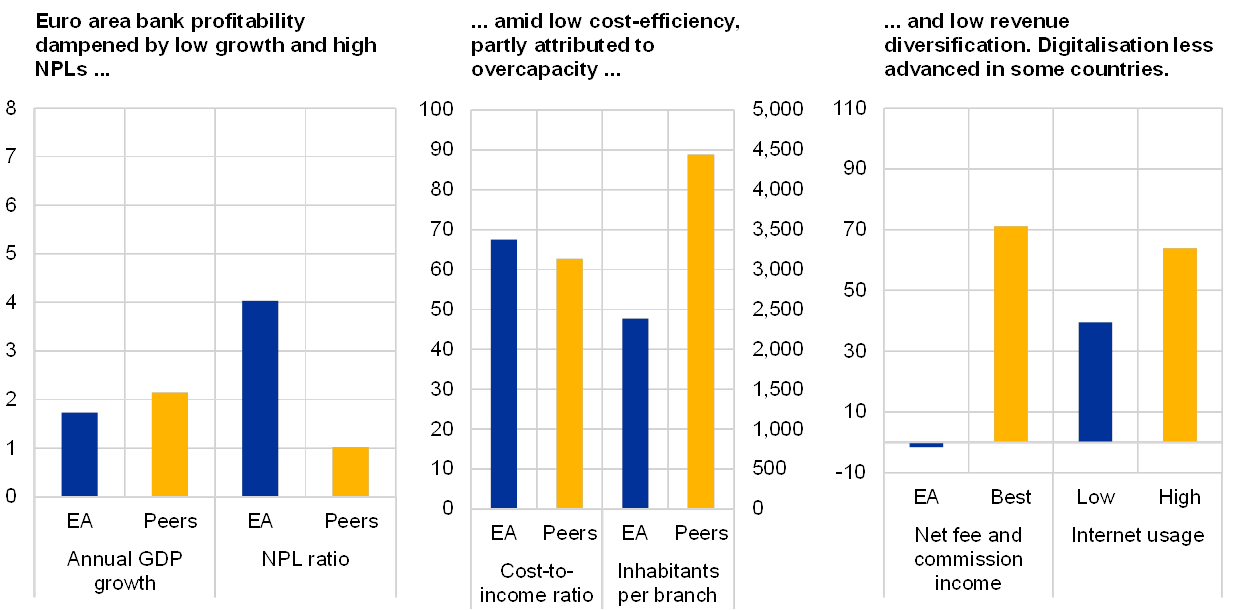

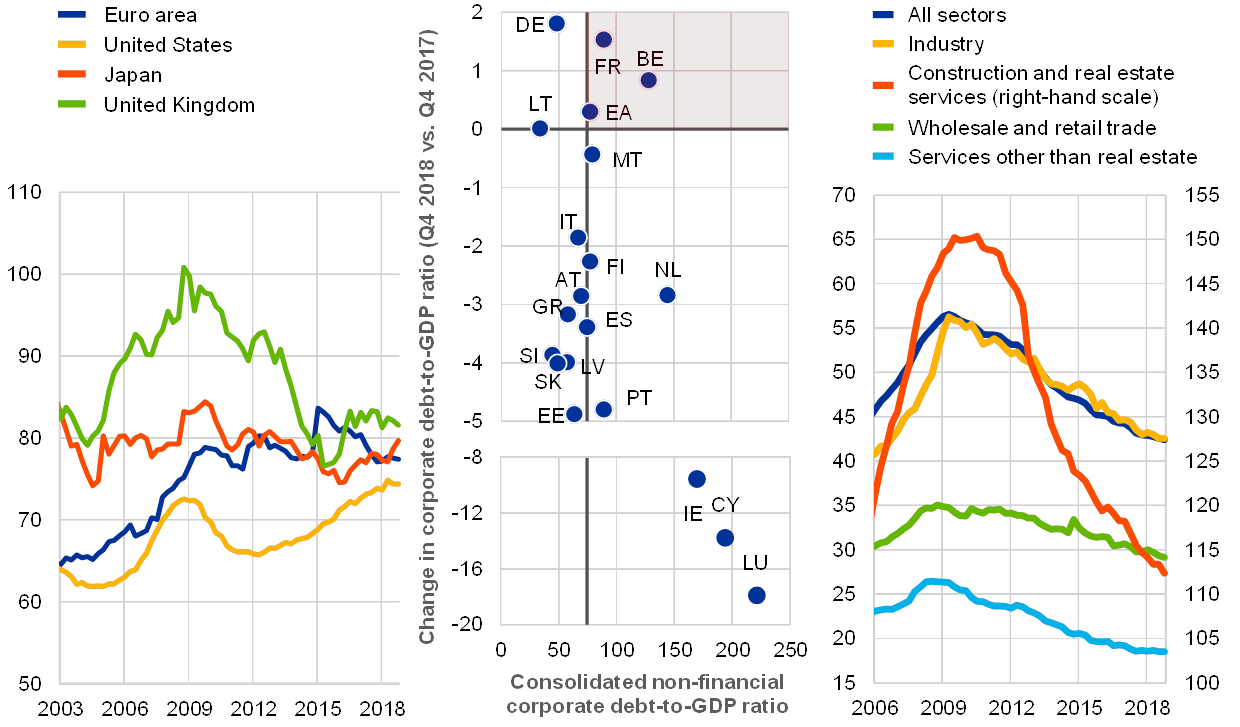

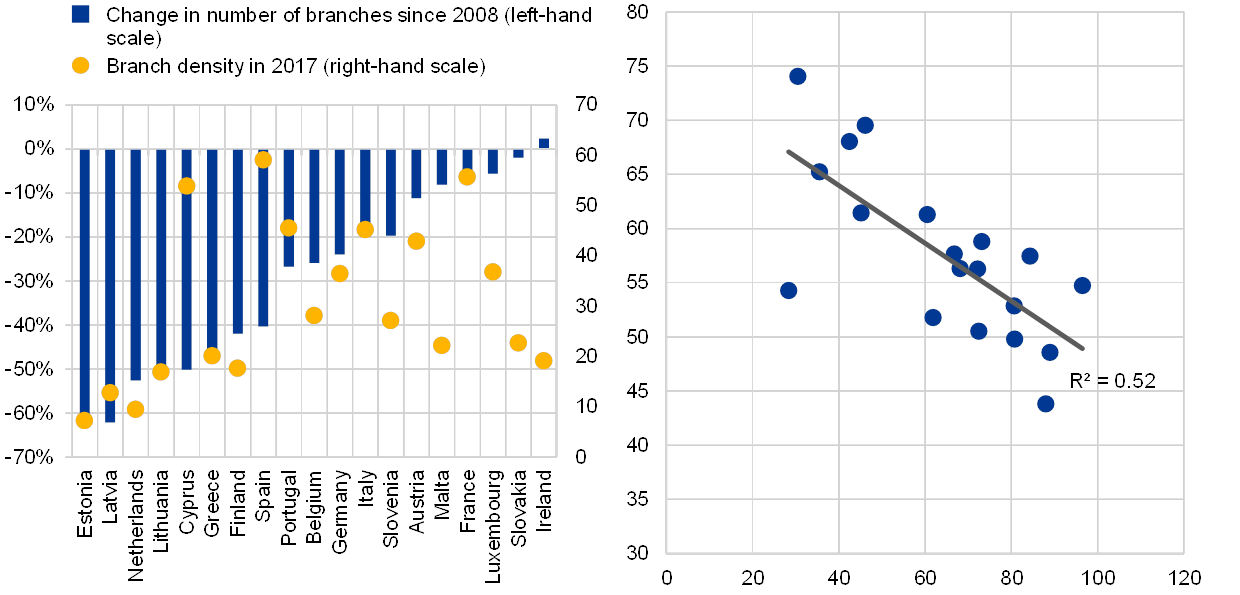

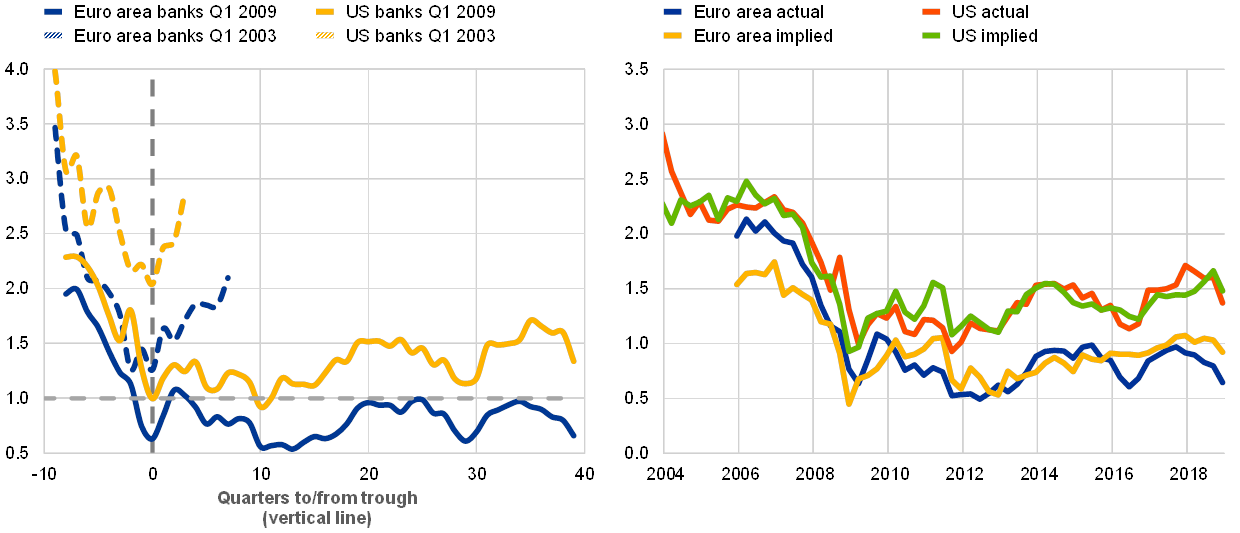

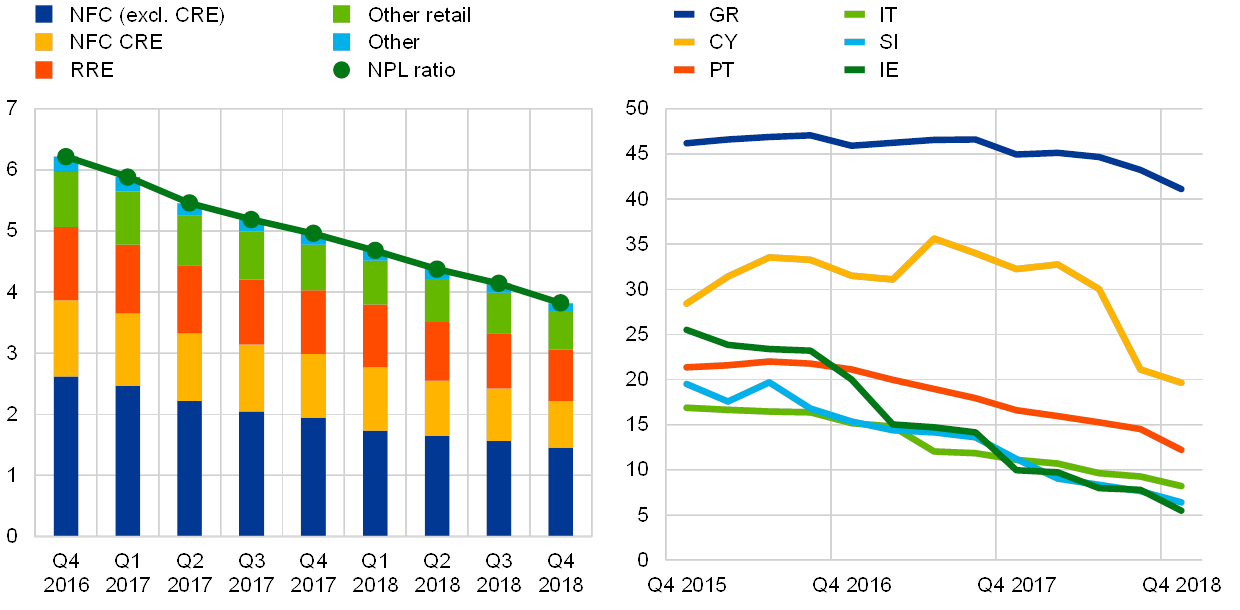

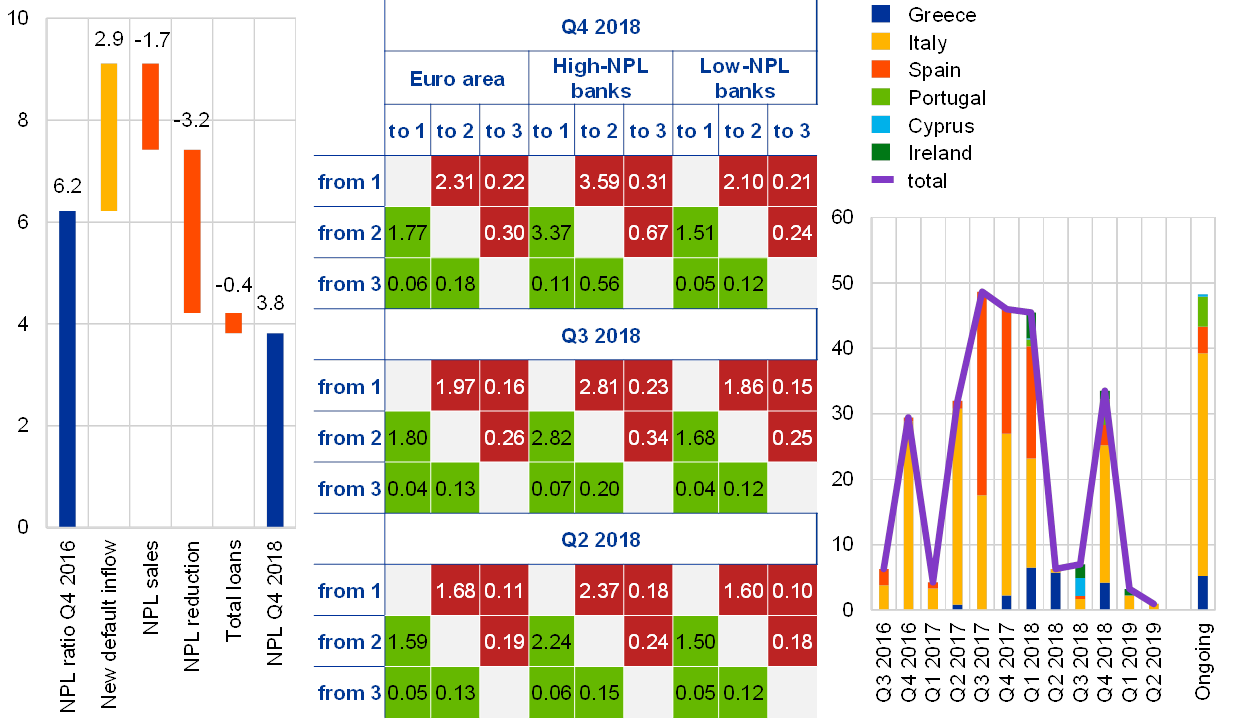

The lower profitability of euro area banks compared with their global peers partly stems from the weak growth environment and high non-performing loans (NPLs). GDP growth in the euro area has been lagging behind that in other major economies in recent years (see Chart 7).[3] As a result, euro area banks have had to manage a large stock of NPLs. Over the past two years, however, euro area significant institutions’ aggregate NPL ratio has fallen by around 2 percentage points, to around 4% in late 2018. That said, the level of NPL ratios remains high in some countries and further efforts are needed to bring them down. Apart from stepping up loan loss provisions, a more active secondary market – including NPL transaction platforms – for impaired assets could support the process.

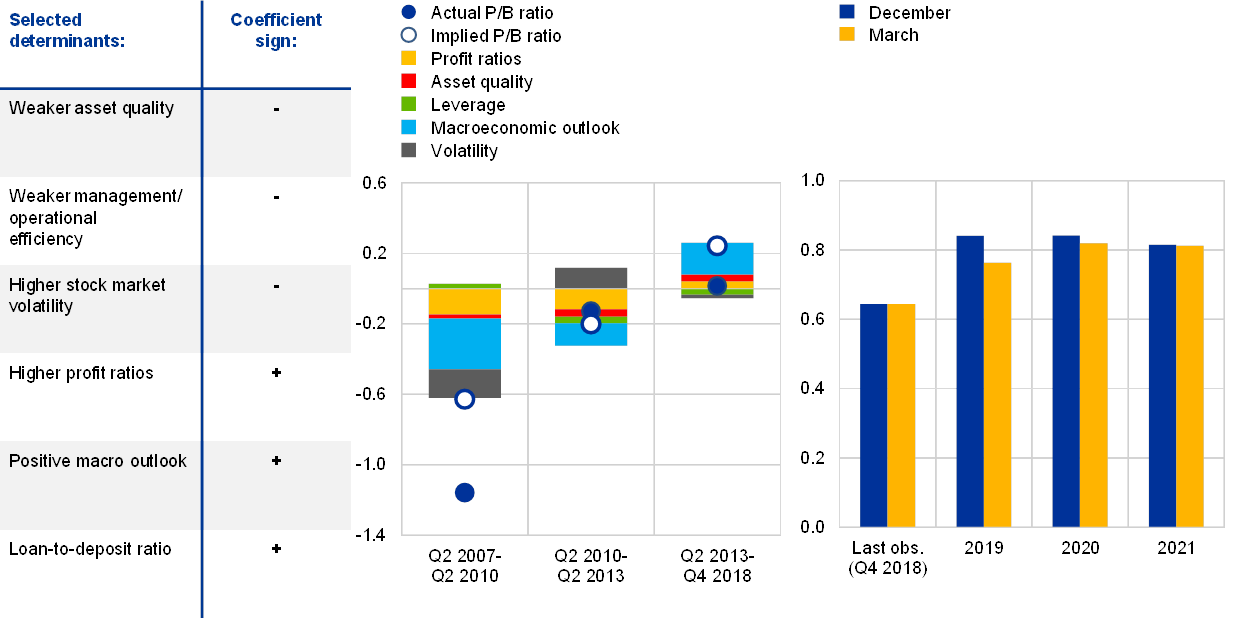

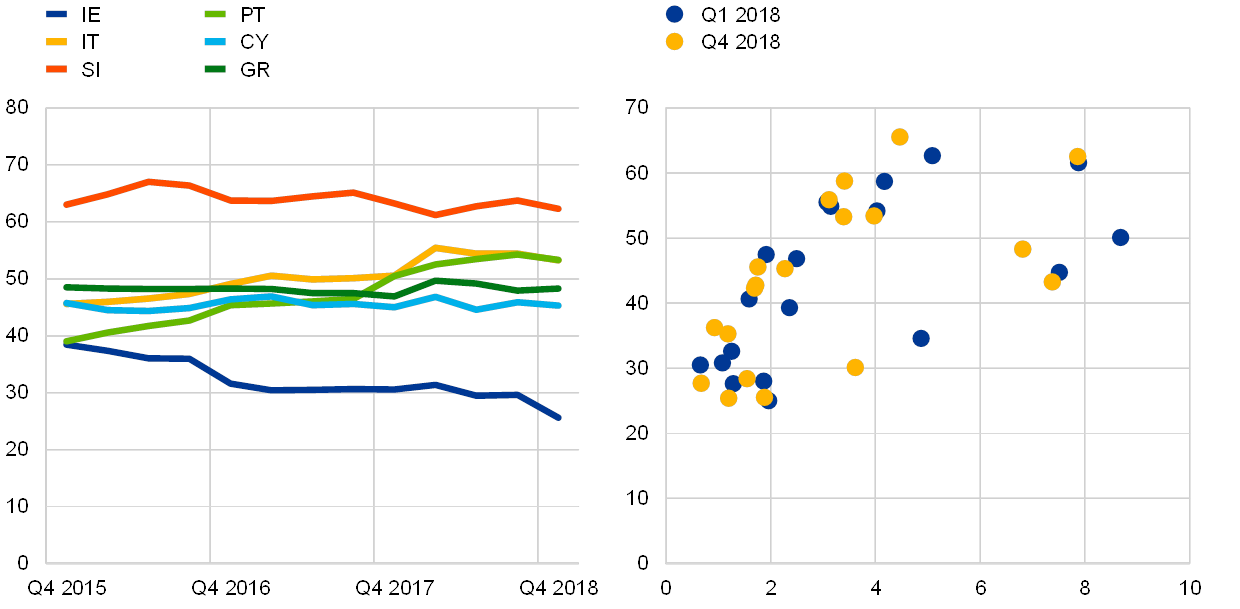

In order to return to sustainable profitability, euro area banks need to tackle a number of structural challenges (see Chart 7). Persistent low bank profitability is a concern from a financial stability perspective as it makes capital raising difficult in case of need and constrains internal capital generation, thus limiting the build-up of buffers against unexpected shocks. A significant part of the profitability gap vis-à-vis international peers is explained by lower cost-efficiency as measured by cost-to-income ratios. On the cost side, euro area banks compare unfavourably with many banks in other advanced economies on metrics such as the number of inhabitants per branch and staff costs. While there is no one-size-fits-all strategy for business model adjustment, one way for banks to improve cost-efficiency would be to speed up the digital transformation and shift away from physical branch networks. Governments may facilitate such a transformation by enhancing internet usage among the general public. On the revenue side, a further shift towards fee and commission-based activities could pave the way to higher profitability. Such a shift may be particularly important for banks that rely heavily on net interest income which may come under further pressure if interest rates were to stay low for longer. In fact, there is evidence that banks which have performed better in recent years (in terms of profitability and cost-efficiency) have been able to diversify their income towards fee-based sources.

Chart 7

Structural challenges at the core of weak euro area banking sector profitability

Macro environment and NPLs (left panel); cost-to-income ratio and inhabitants per branch (middle panel); revenue diversification and internet usage (right panel)

(left panel: average annual GDP growth in 2011-18 and NPL ratio as a percentage of total loans in 2018; middle panel: average cost-to-income ratio in 2014-18 and inhabitants per branch (right-hand scale); right panel: net fee and commission growth in 2009-18, internet usage as a percentage of the population, low and high usage across euro area countries (right-hand scale))

Sources: Standard & Poor’s, Bloomberg, IMF Financial Stability Indicators, IMF World Economic Outlook, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, national central banks, Eurostat, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Peers are a weighted average of large banks in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. Net fee and commission income for best-performing banks (Best) covers 13 significant institutions. For more details, see the November 2018 FSR special feature entitled “How can euro area banks reach sustainable profitability in the future?” Low internet usage countries: Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain; high internet usage countries: Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands.

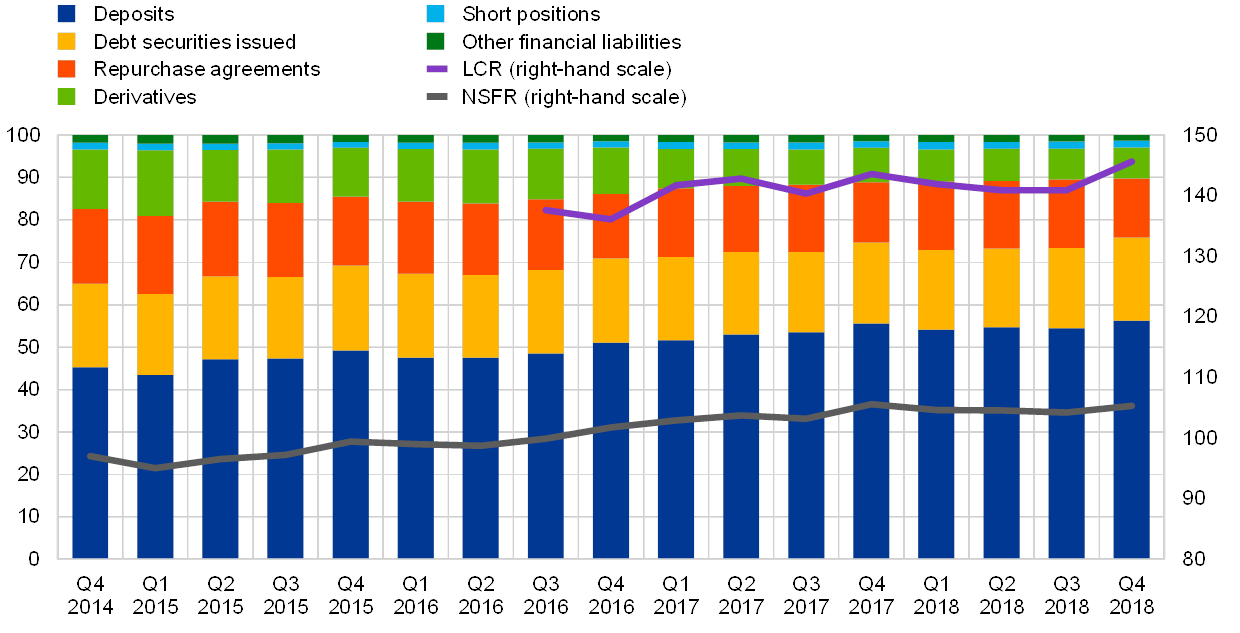

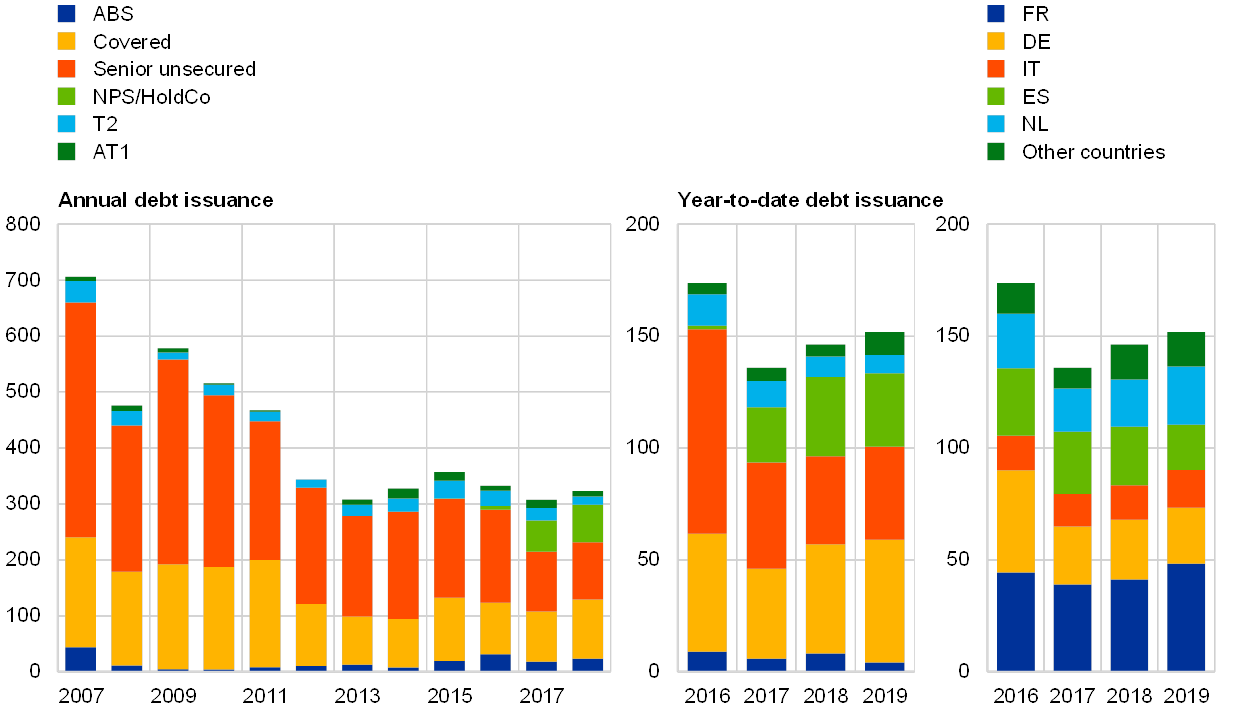

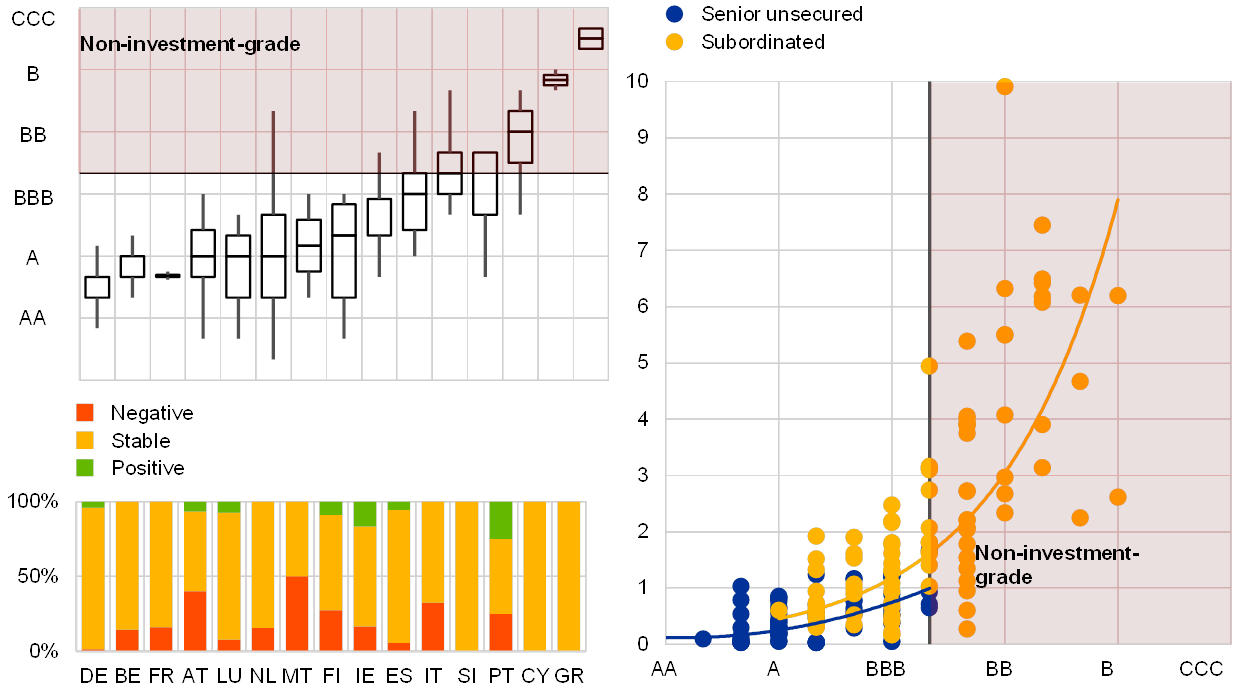

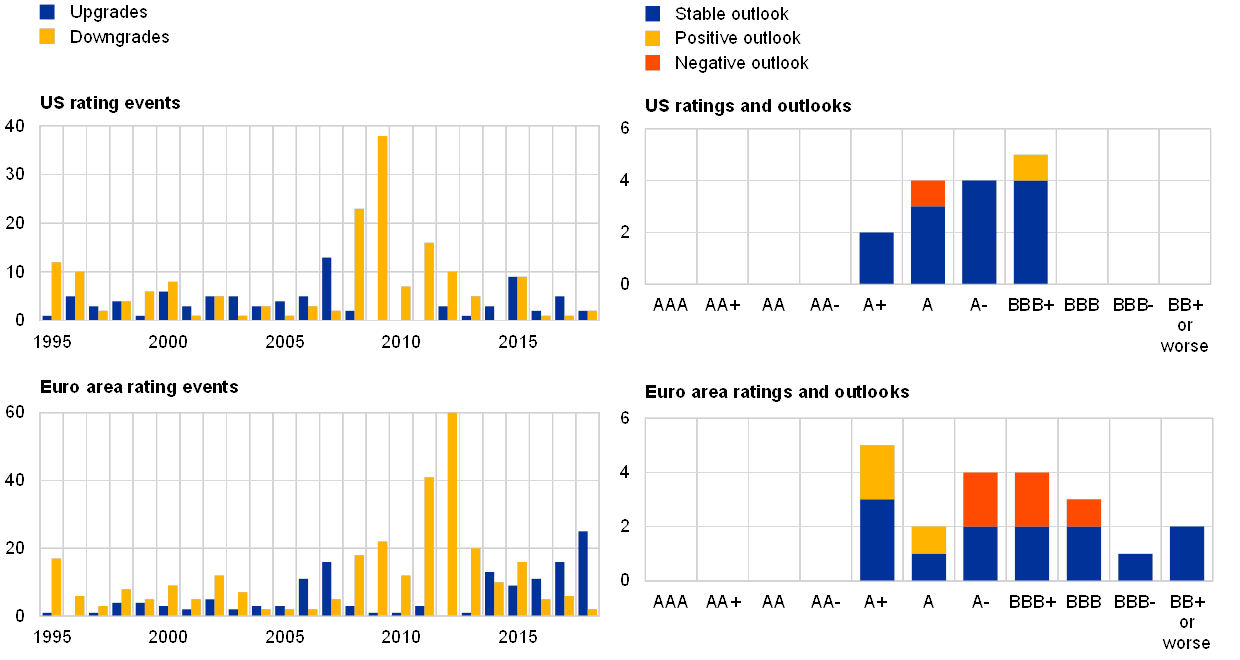

Some banks could face funding cost pressure if economic growth surprises on the downside. Market-based funding costs for euro area banks have remained volatile over the past six months. Spreads widened in the latter part of 2018, but tightened by similar magnitudes in the first months of 2019. Going forward, funding conditions may come under further pressure as a result of a sharper than expected cyclical downturn or a re-emergence of sovereign stress in countries that face debt sustainability challenges. Furthermore, rating downgrades are relatively likely for some banks which might also put further pressure on banks’ funding costs. The issuance of new bail-inable debt might also prove challenging for some banks, in particular for those with lower ratings. In addition, while the launch of the new series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO-III) should help banks refinance maturing TLTRO-II funds, some banks with weaker funding profiles need to develop plans for eventually replacing central bank funding with longer-term market funding, which could add to funding cost pressures for these banks in the medium term.

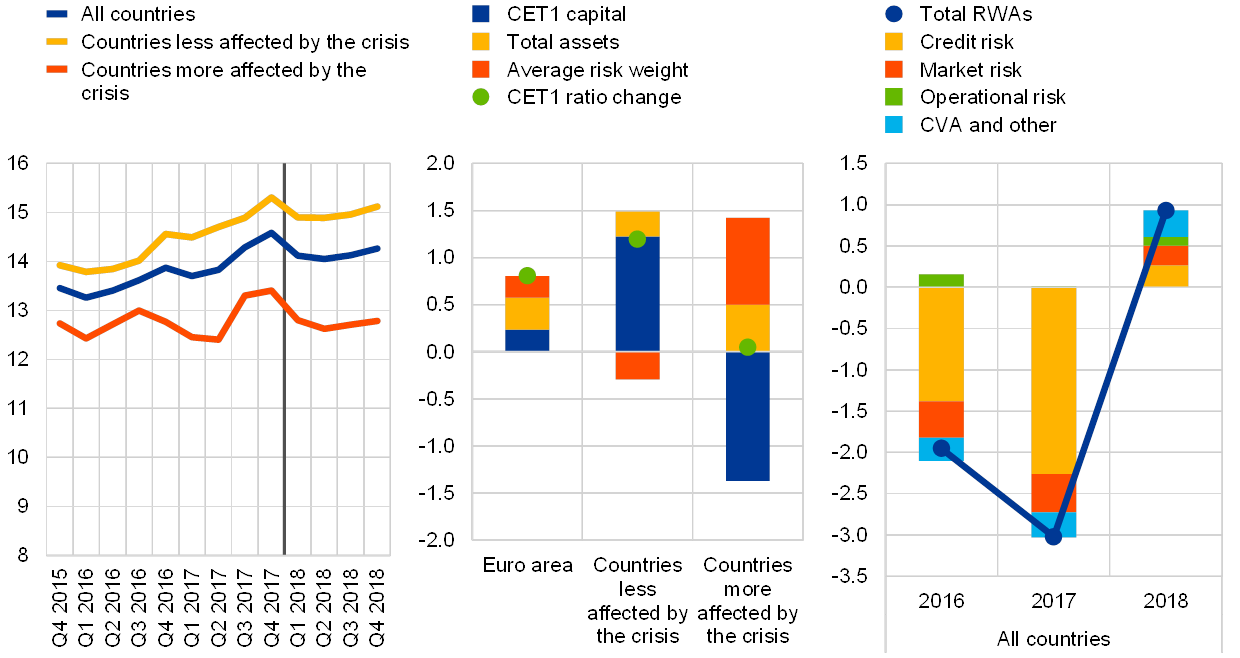

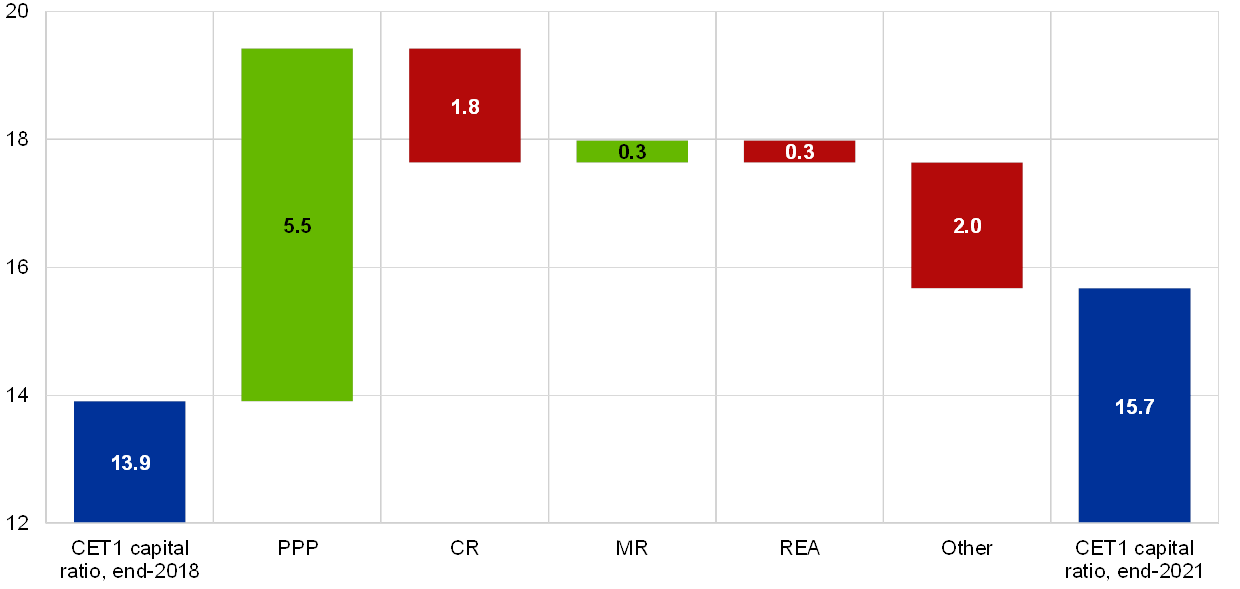

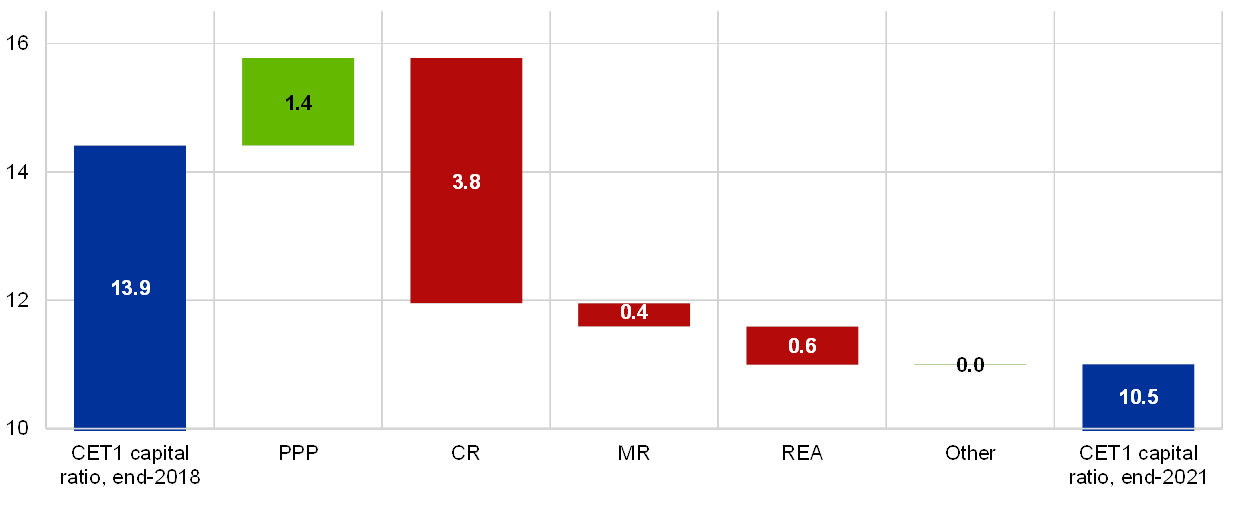

Regulatory capital ratios of euro area banks appear resilient to an adverse macroeconomic scenario. Euro area significant institutions’ aggregate Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio remained broadly stable in the last three quarters of 2018 at around 14%. Over the last four years the aggregate CET1 ratio for euro area banks has increased by around 3 percentage points, driven by both an increase in CET1 capital and a reduction in risk-weighted assets. The results of a stress test based on a scenario with a prolonged period of low economic growth showed that despite the 340 basis point depletion of the CET1 capital ratio, banks still had 10.5% CET1 at the end of 2021. This suggests that the euro area banking sector as a whole should be resilient to a range of downside risks.

Policy responses to ensure resilience

Macroprudential policy action

A number of jurisdictions have activated or increased the countercyclical capital buffer. Over the last year a number of euro area countries have implemented macroprudential policy measures to address the build-up of systemic risk. In particular, the countercyclical capital buffer was activated or increased in France, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Slovakia. Despite the economic headwinds, further increasing macroprudential policy space in some countries appears desirable to build bank resilience and insure against the materialisation of tail events. Nevertheless, macroprudential policy should take into account the risk of inducing procyclical effects, which is most relevant in countries where macroeconomic conditions are relatively weak and downside risks to the economic outlook are more prominent. Model-based analysis for the euro area as a whole suggests that procyclical effects from tighter macroprudential policy would be contained if the baseline macroeconomic projections were to materialise (see Special Feature C). However, procyclical effects could emerge in a scenario in which macroeconomic conditions deteriorate strongly and financial conditions tighten substantially.

A number of euro area countries have activated macroprudential instruments over the past years to address residential real estate-related vulnerabilities. Twelve countries (i.e. Austria, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia) have activated borrower-based instruments, such as loan-to-value (LTV), debt service-to-income (DSTI), loan-to-income (LTI), debt-to-income (DTI) and maturity limits, usually with the aims of strengthening household and bank resilience, as well as ensuring that lending standards remain appropriate. In addition, five countries (i.e. Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta) have capital measures in place, such as risk weight floors or add-ons on mortgage loans, with the primary objective to increase banks’ resilience to shocks in the housing market. Since mid-November 2018 two countries have notified macroprudential policy changes to address residential real estate risks. Malta announced the introduction of binding limits on LTV and DSTI ratios and on maturity at loan origination (which will become effective in July 2019), while Slovenia extended the existing recommendation on LTV and DSTI limits on mortgage loans to consumer loans and complemented these limits with maturity requirements on consumer loans.

While macroprudential policies targeting residential real estate appear sufficient in most of the euro area countries, in some, the policy stance may need to be adjusted and further policy actions should be considered by national authorities. In particular, at the current stage of the cycle, it is important to monitor the quality of lending standards in order to ensure that new mortgage borrowers are resilient to income and interest rate shocks, and that banks are resilient to accumulated vulnerabilities in some of the euro area countries. To ensure the resilience of borrowers going forward, national authorities should require banks to test the debt servicing capacity of borrowers at loan origination against plausible income and interest rate scenarios. More generally, national authorities should provide (or enhance) public guidance to banks on prudent lending standards and consider, at least, indicative quantitative limits on key ratios (e.g. LTV, DTI and DSTI) if this is deemed necessary in order to address the identified risks.

Strengthening the regulatory framework

Regulatory initiatives at the international and EU levels are vital in establishing a sound and robust framework for financial institutions, markets and infrastructures. A key achievement in this regard was the political agreement reached on the EU banking reform package in February 2019. The package includes the revision of the Capital Requirements Regulation and Directive (CRR/CRD IV), which will implement the Basel capital and liquidity standards (Basel III) in EU law, including the leverage ratio, the net stable funding ratio and the revised market risk capital framework. The CRR/CRD IV review also introduces major changes in the macroprudential regulatory and policy framework by: (i) clearly delineating the responsibilities of micro- and macroprudential authorities; (ii) enhancing the flexibility of the toolkit; and (iii) streamlining the activation and coordination mechanisms. These changes will allow macroprudential authorities to address systemic risks in a more effective and targeted manner in the future. Furthermore, political agreement has also been reached on the revision of the ESRB Regulation, which will improve the transparency and functioning of the European Systemic Risk Board, while maintaining its proximity to the ECB.

Removing the remaining barriers to the banking union and making further progress towards a genuine capital markets union are key to facilitate a more complete pan-European market. In this regard, further steps need to be taken to foster a higher level of financial integration and to assess its potential impacts on financial stability. The development of a common institutional framework – including the establishment of a European deposit insurance scheme as the third pillar of the banking union – and reducing remaining obstacles to cross-border banking activities can help improve operating cost efficiency and revenue diversification of European banks.

Strengthening the regulatory framework for non-bank financial intermediation is crucial in order to limit regulatory arbitrage and enhance the resilience of the broader financial system. Non-bank financial intermediation has been growing in the euro area, which has potential implications for financial stability and the financing of the real economy more broadly. The increasing size of non-banks has been accompanied by rising liquidity and credit risks in their investment portfolios. While existing rules in the EU provide a robust framework to address investor protection and entity-specific vulnerabilities, there are growing concerns over cyclical risks associated with increased liquidity transformation, risk-taking and leverage affecting the sector more broadly. Against this background, it is necessary to broaden the macroprudential toolkit and operationalise existing tools[4] for non-bank financial intermediation – and for investment funds in particular – to address new and emerging risks from non-bank financial intermediation. At a global level, it is important to develop a consistent reporting framework for leverage in investment funds, with a view to gaining a system-wide perspective on evolving risks, in line with the recommendations of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to the International Organization of Securities Commissions.[5] Looking ahead, in the context of the FSB’s work on the evaluation of post-crisis reforms, it would be useful to assess the effectiveness and completeness of the regulatory measures taken in relation to the non-bank financial sector.

1 Macro-financial and credit environment

1.1 Weaker near-term euro area growth outlook coupled with persistent downside risks

The euro area economy lost some momentum in late 2018. Notwithstanding a rebound of GDP growth at the start of 2019, survey indicators continue to point to a subdued economic expansion in the near term. The slowdown in euro area growth (see Chart 1.1, left panel) can be attributed to weaker impetus from external demand as well as some country and sector-specific factors, such as disruptions in the German car industry and adverse confidence effects of the political and policy uncertainties in Italy. That said, the ECB’s accommodative monetary policy has continued to underpin domestic demand. Ongoing favourable labour and housing market trends have also buttressed private consumption, while benign financing conditions and relatively resilient corporate and household fundamentals underpinned business and residential investment.

Chart 1.1

Moderation in euro area cyclical momentum and lower inflation outturns reflect expected temporary slowdown in nominal growth

Real GDP growth, Economic Sentiment Indicator and composite output PMI for the euro area (left panel), as well as HICP inflation, HICP inflation excluding energy and food and inflation expectations in the euro area (right panel)

(left panel: Jan. 2011-Apr. 2019, quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, diffusion index: 50+ = expansion; middle panel: 2013-21, percentage points; right panel: Jan. 2011-Apr. 2019, annual percentage changes, percentages)

Sources: Markit, European Commission, Eurostat, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the Economic Sentiment Indicator is standardised and rescaled to have the same mean and standard deviation as the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). Right panel: the vertical line indicates the latest data point available at the time of the publication of the previous FSR.

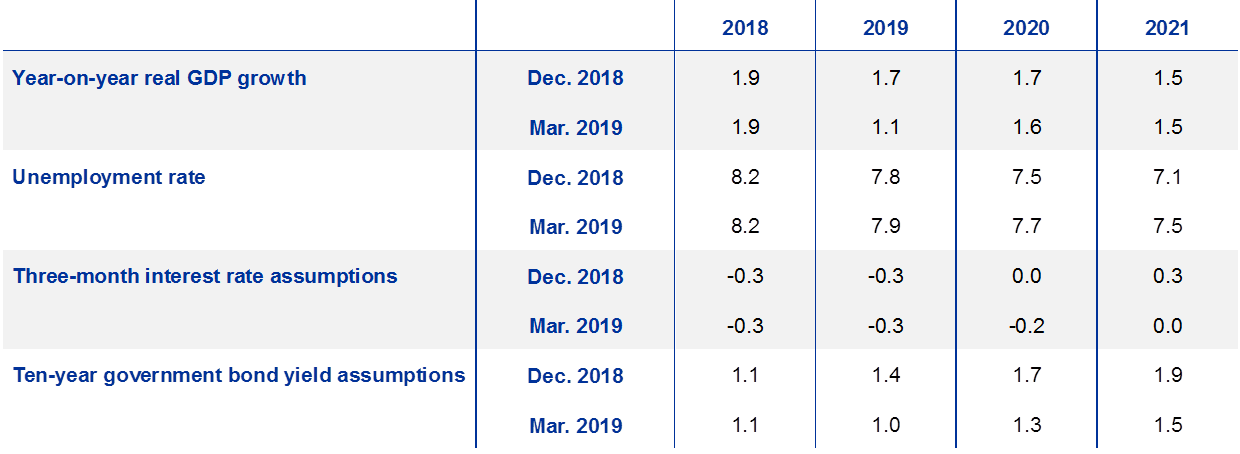

The euro area expansion is expected to regain traction amid supportive fundamentals. Looking ahead, growth of the euro area economy is projected to gradually strengthen, reflecting the favourable impact of very accommodative monetary policy, rising wages, a recovery in foreign demand and some fiscal loosening. The March 2019 ECB staff macroeconomic projections foresee real GDP growth strengthening in the medium term from the moderate rate of 1.1% in 2019 to 1.6% in 2020 and 1.5% in 2021. Weaker economic growth prospects in the near term together with lower HICP inflation outturns since the publication of the previous FSR (see Chart 1.1, right panel) translate into more muted headline HICP inflation forecasts of 1.2% in 2019, followed by 1.5% in 2020 and 1.6% in 2021. This nominal growth path in the euro area contrasts with more favourable economic prospects in the United States, despite a deterioration of the 2019 growth and inflation outlook for both jurisdictions (see Chart 1.2).

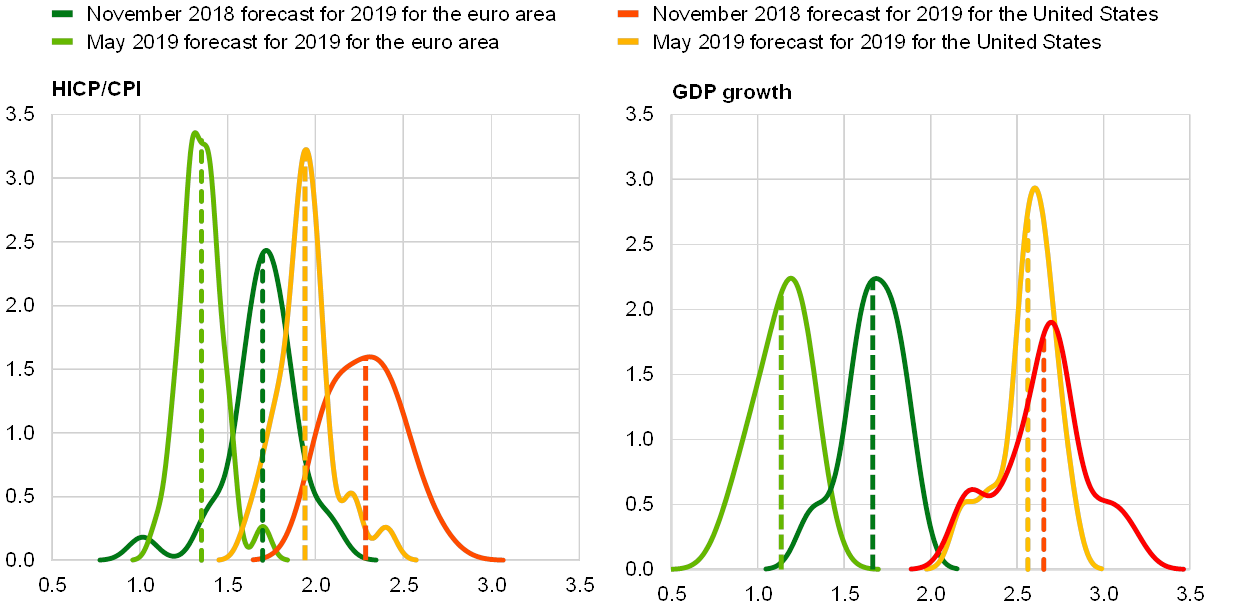

Chart 1.2

Real GDP growth and inflation have been revised down for both the euro area and the United States amid increasing downside risks

Distribution of the 2019 HICP/CPI and real GDP growth forecasts for the euro area and the United States

(probability density)

Sources: Consensus Economics and ECB calculations.

Notes: The dashed lines represent the average HICP/CPI and real GDP growth forecast values. HICP stands for Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices and CPI for Consumer Price Index.

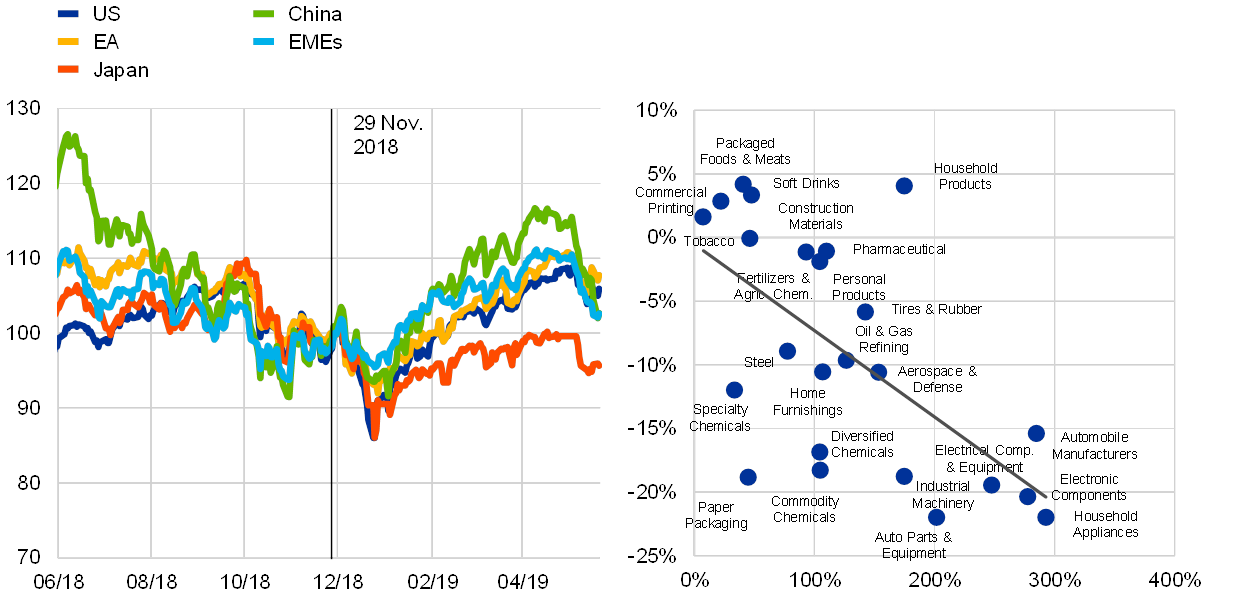

Growth of the global economy slowed at the turn of 2018-19, but is set to stabilise in the medium term. The slowdown has been fairly pronounced in the manufacturing sector against the backdrop of the maturing business cycle in key advanced economies, while global trade decelerated sharply (see Chart 1.3, left panel) amid slowing industrial activity and heightened trade tensions. The slowdown in global growth went hand in hand with lower global inflationary pressures and more accommodative monetary policy expectations by market participants in most major advanced and emerging market economies (EMEs) (see Chart 1.3, middle panel). Global growth is expected to stabilise over the medium term as slowing cyclical momentum in advanced economies, as well as a gradual slowdown in China’s GDP growth, are largely offset by the recovery of key EMEs from deep recessions (e.g. Russia, Brazil). The accommodative stance by central banks globally has also eased global financing conditions (see Chart 1.3, right panel), creating a more benign environment for EMEs.

Persistent downside risks cloud the global and euro area growth outlook. Alongside waning fiscal and structural reform efforts in some euro area countries, downside risks to euro area growth mainly relate to global factors. In particular, uncertainties regarding the course of the economy and fiscal policies in the United States, a further rise in (geo)political and policy uncertainty across the globe, including in relation to growing trade protectionism and a disorderly no-deal Brexit, as well as renewed tensions in EMEs, may weigh on the euro area growth momentum.

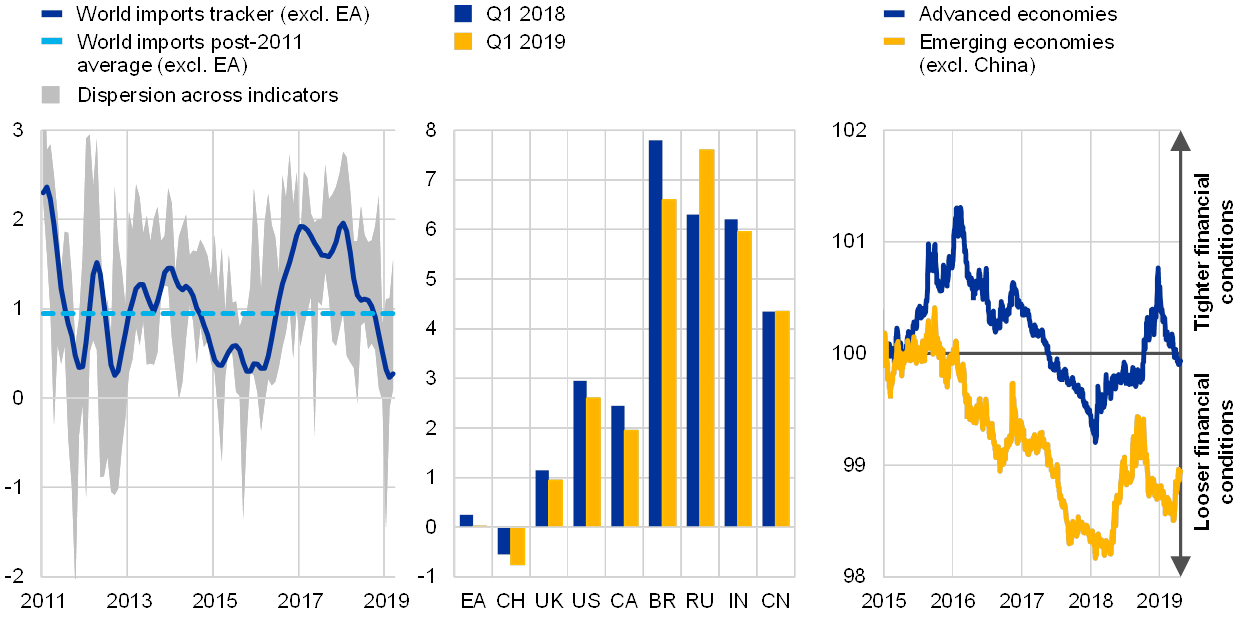

Chart 1.3

Growth in global activity and trade slowed since mid-2018, while financial conditions eased in early 2019 amid expectations of more accommodative monetary policy

Global trade tracker (left panel), expected policy rates in Q4 2019 based on market expectations in Q1 2018 and Q1 2019 for major advanced economies and the BRIC countries (middle panel), as well as financial conditions across the globe (right panel)

(left panel: Jan. 2011-Mar. 2019, quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; middle panel: percentages; right panel: Jan. 2015-Apr. 2019, indices, Jan. 2015 = 100)

Sources: ECB calculations, Markit and Goldman Sachs (via Bloomberg).

Notes: Left panel: the tracker is based on a dynamic factor model using 22 monthly trade indicators. The grey shaded area shows the range of the ten highest-loaded indicators. Indicators are standardised and mean/variance-adjusted into world imports excluding the euro area.

A more severe slowdown of the US economy could adversely affect global growth and financial markets. The US economy is currently in its second longest expansion on record, buttressed by fiscal stimuli in the late phase of the business cycle. While near-term recession risks in the United States appear to be limited, the equity market corrections at the turn of the year, the ongoing US-China trade dispute, vulnerabilities associated with elevated corporate leverage (see Chapter 2) and weaker global growth prospects have led to continued market concerns regarding the downside risks to US economic growth. In addition, while the negative impact of the partial federal government shutdown earlier this year is expected to be moderate, the current expansionary fiscal policies may trigger public debt sustainability concerns (see Chart 1.4, left panel) and a repricing in US and global bond markets. Nevertheless, the dominant role of the US dollar as an international reserve currency is expected to continue attracting international investors, thereby mitigating the risk of a near-term repricing of US government debt.

Heightened political and policy uncertainty may weigh on global sentiment. Political and policy uncertainty remained elevated at the turn of 2018-19 across the globe (see Chart 1.4, middle panel). Alongside continued uncertainties surrounding economic and fiscal policies in some major euro area countries, a further escalation of trade tensions between the United States and China could have a significant impact on global trade and growth, especially if direct trade effects were to be compounded by indirect confidence effects stemming from increased uncertainty about future trade policies and trading relations. At the same time, the continued lack of clarity on the future relations between the United Kingdom and the European Union also implies uncertainty surrounding financial market sentiment and the growth implications of the UK leaving the EU (see Box 1).

Chart 1.4

Deteriorating US fiscal fundamentals, heightened economic policy uncertainty and a hard landing of the Chinese economy may weigh on global growth prospects

Fiscal fundamentals in the United States (left panel), news-based measures of economic uncertainty and geopolitical risk (middle panel), as well as estimated real GDP impact of spillovers from a China slowdown (right panel)

(left panel: 2003-24, percentage of GDP; middle panel: Jan. 2004-Apr. 2019, index points; right panel: real GDP, percentage deviations from “limited adjustment” scenario after three years)

Sources: IMF (World Economic Outlook database), Caldara and Iacoviello (2017), Baker, Bloom and Davis (2013) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Middle panel: for the geopolitical risk index, see Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M., “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, working paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board, November 2017. Measures of economic policy uncertainty are taken from Baker, S., Bloom, N. and Davis, S., “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty”, Chicago Booth Research Paper No 13/02, January 2013. Right panel: the labels refer to the euro area (EA), the United States (US), Japan (JP), the United Kingdom (UK), oil-producing countries (Oil) and the rest of the world (RoW). For more details on the methodology, see Dieppe, A., Gilhooly, R., Han, J., Korhonen, I. and Lodge, D. (eds.), “The transition of China to sustainable growth – implications for the global economy and the euro area”, Occasional Paper Series, No 206, ECB, January 2018.

Vulnerabilities in emerging market economies remain a cause for concern. The most acute tensions observed in a number of EMEs in 2018 have subsided, but pockets of vulnerability remain across EMEs, as illustrated by the renewed heightened volatility in the most vulnerable economies (e.g. Turkey and Argentina). Despite market participants’ more benign view of emerging markets lately, the fragility of macroeconomic fundamentals – in particular high current account deficits and a strong reliance on US dollar funding – together with limited room for policy support leaves some EMEs exposed to changes in investor sentiment and sudden flow reversals. Moreover, financial and real shocks associated with China’s rebalancing process towards a more consumption-driven growth path and/or its trade dispute with the United States may adversely affect other Asian and Latin American economies with close trade and financial links to the Chinese economy. In addition, such shocks could spark broader-based risk aversion vis-à-vis emerging markets at large, with significant implications for global financial markets and economic activity (see Chart 1.4, right panel).

The materialisation of downside risks to growth could challenge euro area financial stability. In particular, it might spark tensions in global financial markets and prompt a disorderly unwinding of global search-for-yield flows. A weaker than expected growth environment could also trigger the materialisation of any of the main risks to euro area financial stability and could amplify global risk repricing, further challenge bank profitability or fuel debt sustainability concerns.

Box 1

Assessing the risks to the euro area financial sector from a no-deal Brexit – update following the extension of the UK’s membership of the EU

The extension of the UK’s membership of the EU agreed by the European Council on 10 April avoided a no-deal Brexit scenario over the FSR review period. But the risk of a no-deal scenario occurring at the end of the extension period cannot be excluded. The additional time should be used by both financial and non-financial sectors to continue to prepare for all possible contingencies, including a disorderly Brexit. Furthermore, banks should use the period in which the UK remains in the EU to make progress towards their target operating models within the timelines previously agreed with their supervisors.

A no-deal Brexit poses manageable risks to overall euro area financial stability and authorities have prepared for this scenario.[6] Action has been taken where necessary (for example, in the area of market infrastructures), and the private sector has made progress in certain areas to address Brexit-related risks. Nevertheless, there remain tail macro-financial risks whereby a no-deal Brexit interacts with other global shocks, in an environment where risks to the euro area growth outlook are tilted to the downside. If such a scenario occurs, the impact would likely be concentrated on particular countries, such as those with significant ties to the UK. This could be further amplified by any lack of preparedness among clients in the financial sector and certain key sectors of the real economy. It is also important to acknowledge that the extent of non-linear effects which might occur in such a scenario cannot be fully predicted.

The materialisation of a no-deal scenario may entail substantial financial market volatility and an increase in risk premia. Market intelligence suggests that financial market prices reflect only a low probability of a no-deal scenario, although uncertainty among market participants remains elevated in light of on-going political developments. So a no-deal outcome could lead to substantial market turbulence. On 5 March, the Bank of England and the ECB announced the activation of the currency swap arrangement for the possible provision of euro to UK banks. As part of the same agreement, the Eurosystem would also stand ready to lend pounds sterling to euro area banks. The activation marks a prudent and precautionary step by authorities to provide additional flexibility in their provision of liquidity insurance, supporting the functioning of markets that serve households and businesses.

Combined with an impact via trade channels, potential financial market shocks related to a no-deal scenario pose a material downside risk to euro area GDP growth. Beyond having an impact on euro area growth, a no-deal Brexit is also likely to precipitate an even more significant macroeconomic shock in the UK.[7] In terms of the implications of this potential macroeconomic shock for the euro area banking system, it should be noted that direct exposures to the UK only accounted for about 7% of SSM significant institutions’ assets at the end of 2018. Of this, loans represent less than 5% of total assets, with much of the remainder made up of derivatives contracts held with UK counterparties. At the same time, these macro-financial tail risks would likely have concentrated effects on particular countries and banks.

In relation to derivatives markets, cliff-edge risks in the area of cross-border centrally cleared derivatives have been addressed through the temporary equivalence decision of the European Commission for UK central counterparties until 30 March 2020. Issues related to uncleared derivatives are also unlikely to pose a systemic risk. In a no-deal scenario, euro area institutions will continue to be able to hedge risks through uncleared derivatives markets using non-UK counterparties – indeed, business with UK counterparties comprises less than a third of outstanding contracts held by euro area institutions. The private sector has also made some progress in addressing risks associated with the existing stock of contracts. Should market participants wish to adjust the remaining stock of contracts, there are a range of options available to them to do so. The private sector should make use of the risk mitigants available to them over the coming months to ensure that they are fully prepared for a no-deal scenario.

Financial stability risks are not expected in the area of cross-border insurance contracts. In particular, UK insurance companies servicing EEA30 policyholders have several options to mitigate any disruption and these options are being actively used by firms. As a result, the vast majority of outstanding cross-border insurance contracts are covered by credible contingency plans, with the residual contracts primarily pertaining to non-life insurers.[8]

In terms of relocation planning, the majority of authorisation procedures related to the establishment of new banks or the expansion of existing banks in the euro area have been completed. The remaining ongoing authorisation procedures are expected to be finalised before the end of October 2019. So no major disruptions in the servicing of EU clients are expected. Banks are now in the process of implementing their Brexit plans, including the transfer of capital, assets and client activities. Going forward, the ECB expects banks to build up their capabilities in the EU27 and to reach the agreed target operating models within the previously agreed timelines.

Overall, the risk that the euro area real economy would be deprived of access to financial services following the UK’s departure from the EU appears limited. But macro-financial tail risks may have implications for parts of the euro area financial system. The extension period should be used by both financial and non-financial sectors to continue to prepare for all possible contingencies, including a disorderly Brexit.

1.2 Fragile public debt sustainability

Stress remained subdued in euro area sovereign debt markets, but uncertainties at the country level prevail. Despite the signs of slower economic growth, the composite indicator of systemic stress in euro area sovereign bond markets (SovCISS) has declined somewhat since the turn of 2018-19. This largely reflects the subsiding of acute stress in Italian government bond markets and the continuing positive news flow (e.g. sovereign rating upgrades) on some euro area countries that were more affected by the crisis (e.g. Greece, Portugal). Cross-country dispersion still remains though (see Overview), as markets continue to discriminate between sovereign vulnerabilities at the country level. In terms of the drivers, somewhat lower correlations among input variables exerted downward pressure on the indicator (see Chart 1.5, left panel).

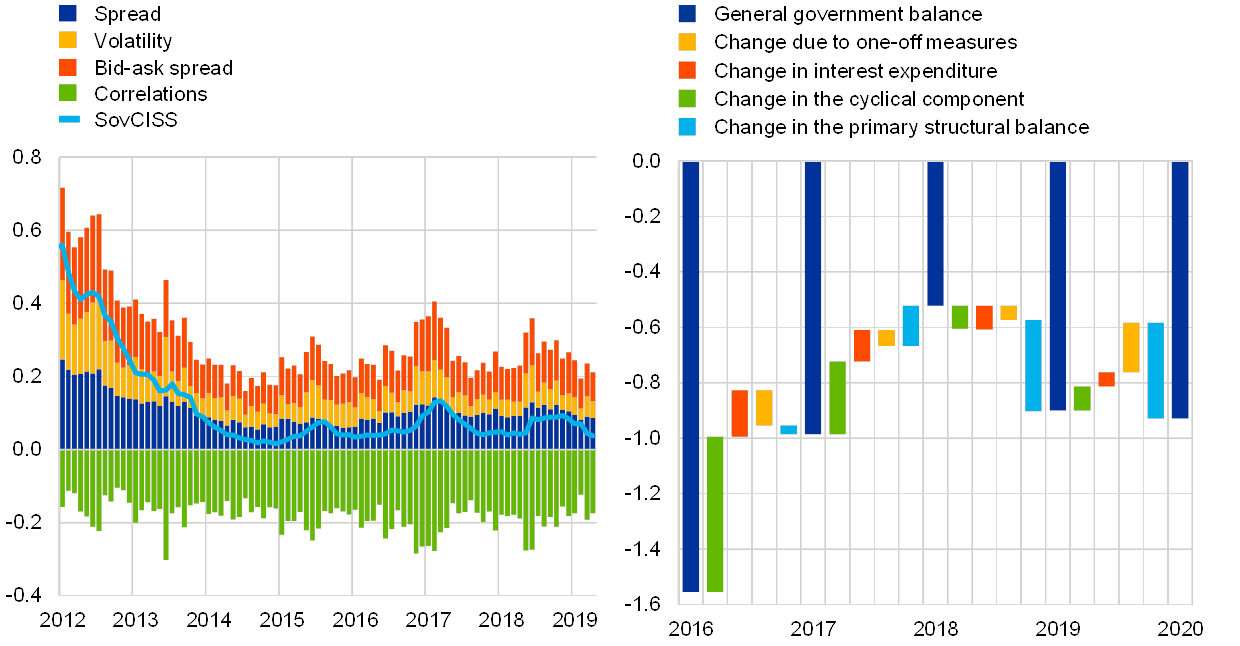

Chart 1.5

Stress in euro area sovereign bond markets has remained contained at the aggregate euro area level amid rising risks of deteriorating fiscal fundamentals

Composite indicator of systemic stress in euro area sovereign bond markets and underlying driving factors (left panel), as well as the headline euro area general government balance and contributing factors (right panel)

(left panel: Jan. 2012-Apr. 2019; right panel: 2016-20, percentage of GDP and percentage point contributions)

Sources: ECB, European Commission’s spring 2019 economic forecast and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the SovCISS is available for the euro area as a whole and for 11 euro area countries. The methodology of the SovCISS is described in Garcia-de-Andoain, C. and Kremer, M., “Beyond spreads: measuring sovereign market stress in the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2185, ECB, October 2018. Right panel: the cyclical component is calculated as the difference between the general government budget balance and the cyclically adjusted general government budget balance which takes the effects of the economic cycle into account. One-off measures capture for example one-off banking support measures or one-off state guarantees to sub-national governments and public and private corporations.

Slower than expected growth and a looser fiscal stance could put pressure on fiscal fundamentals. The aggregate euro area fiscal deficit declined from 1.0% of GDP in 2017 to 0.5% of GDP in 2018 (see Chart 1.5, right panel). This improvement was chiefly driven by favourable cyclical conditions and lower interest payments. However, the aggregate deficit is projected to increase this year for the first time since 2009 on account of lower cyclical support and more expansionary policies than previously expected in several of the largest euro area countries. The projected deterioration of structural balances in 2019 may further challenge the compliance with the medium-term budgetary objectives of a number of highly indebted countries, where fiscal space for countercyclical action is more limited. At the same time, for all euro area countries, shifting expenditure to the most growth-enhancing categories (e.g. investment, education or health) or the tax burden to the less distortive tax bases of consumption and property can positively affect output growth and reduce inequalities.[9]

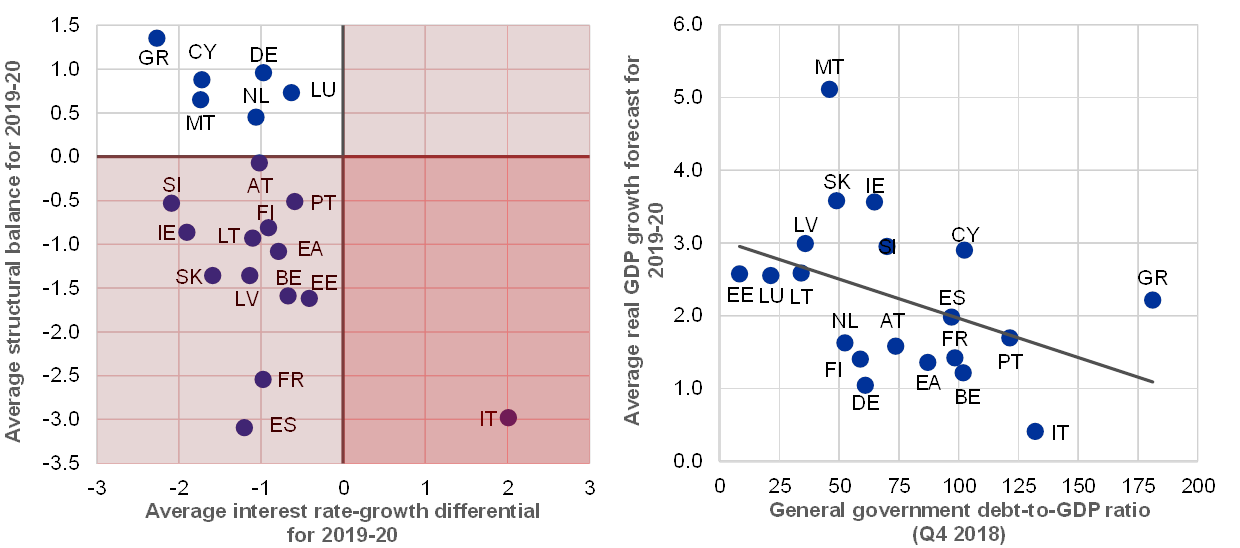

Chart 1.6

Deteriorating growth prospects suggest the importance of more fiscal discipline in those countries with the least fiscal space

Average interest rate-growth differentials and structural balances for 2019-20 across the euro area (left panel), as well as general government debt-to-GDP ratios in Q4 2018 and average real GDP growth forecasts for 2019-20 (right panel)

(left panel: 2019-20, percentage of GDP; right panel: Q4 2018, 2019-20, percentage of GDP, percentages)

Sources: European Commission’s spring 2019 economic forecast, ECB (Government Finance Statistics) and ECB calculations.

Heightened political and policy uncertainty could also add to public debt sustainability concerns. Supported by favourable macro conditions, the euro area aggregate government debt-to-GDP ratio has been on a decreasing path since the peak in 2014, reaching 87.1% in 2018. Looking ahead, beyond slower growth, several other factors may challenge the sustainability of public finances. First, a further rise in political and policy uncertainty at both the country (e.g. elections, economic policies) and EU (e.g. Brexit, upcoming EU elections) levels may cause shifts in market sentiment and trigger a repricing of sovereign risk (see Box 2). In particular, a lack of fiscal discipline, the delay of fiscal and structural reforms, or even the reversal of past reforms, may reignite pressures on more vulnerable sovereigns (see Chart 1.6, left panel). In fact, if weaker economic growth prospects were to be coupled with an interest rate shock stemming from a sovereign risk repricing, that would increase debt sustainability concerns in highly indebted countries and amplify the adverse feedback loop between debt levels and underlying macroeconomic dynamics (see Chart 1.6, right panel). Second, pockets of risk surrounding the sovereign-bank nexus may represent a challenge to public finances in some countries. In the medium-to-long run, these challenges are compounded by vulnerabilities related to the potential rise in interest rates/yields, lower potential GDP growth and ageing-related costs.[10]

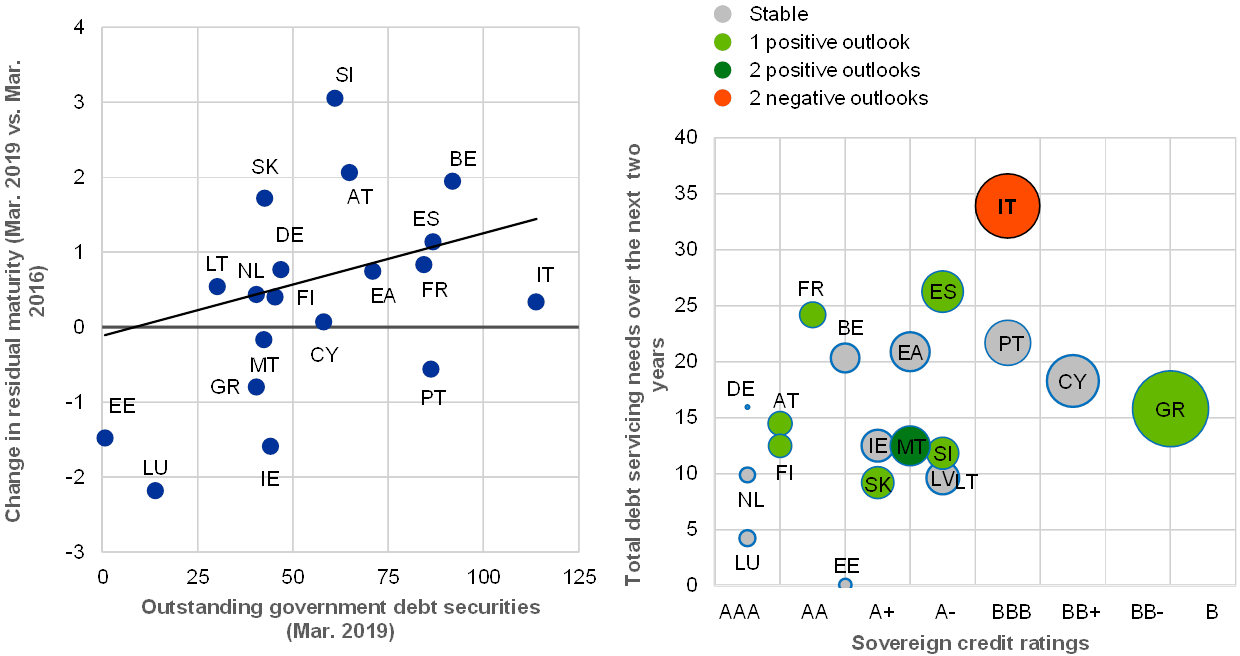

Chart 1.7

The shift towards longer maturity debt has continued, but rollover risks remain elevated in euro area countries with higher debt servicing needs and financing costs

Outstanding amount of government debt securities in the euro area as at year-end 2018 and the change in residual maturity since March 2016 (left panel), as well as sovereign credit ratings and total debt servicing needs over the next two years across the euro area (right panel)

(left panel: Mar. 2019, Mar. 2019 vs. Mar. 2016, percentage of GDP, years; right panel: Mar. 2019, percentage of GDP)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the reference period March 2016 refers to the last interest rate move of the Eurosystem, i.e. the cut of the deposit facility rate by 10 basis points to -40 basis points, while March 2019 refers to the latest available observation. Right panel: the size of the bubble is proportional to the long-term interest rate for convergence purposes (secondary market yields of government bonds with maturities of ten, or close to ten, years). Data on government debt service over the next two years only reflect existing maturing securities (principal and interest). The scheduled (future) redemptions are calculated based on the maturity date for each debt security. The amounts do not include government loans or redemptions of debt securities covering future budget deficits or redemptions of debt securities that will be issued in the future. The rating score represents the average rating by the three major rating agencies, Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch.

Sovereign financing conditions have remained favourable in terms of both pricing and duration. Despite higher sovereign bond yields in some countries, pricing conditions remained relatively benign for euro area sovereigns amid ongoing Eurosystem reinvestment of principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the asset purchase programme. At the same time, benign conditions have also allowed sovereigns to issue at favourable terms. In particular, the trend towards longer durations has continued, with strong issuance activity beyond the 15-year horizon. Countries with high levels of outstanding government debt securities have engaged more in maturity prolongation than those with lower levels (see Chart 1.7, left panel), but not all highly indebted countries have taken advantage of the current favourable financing conditions to the same extent. In terms of the underlying interest rate structure, a reduction in zero-coupon and floating rate debt and the concurrent increase in fixed rate debt allow governments to lock in long-term financing at low costs and to capitalise on historically low interest rates.

A sovereign risk repricing may trigger rollover risks in countries with continued high refinancing needs. The overall shift in net issuance activity towards the long end of the maturity spectrum in recent years has helped to reduce the gross financing needs of euro area governments from over 27% of GDP at the height of the euro area sovereign debt crisis to 21.6% in the first quarter of 2019. However, the euro area aggregate conceals a considerable degree of cross-country heterogeneity. Debt servicing needs remain high for several – in particular the most highly indebted – euro area countries. This may suggest possible pockets of rollover risk in terms of both the availability and the cost of funding in the event of a possible sovereign risk repricing (see Chart 1.7, right panel).

In sum, weaker economic growth and a further rise in political uncertainty could intensify sovereign risks. While favourable financing conditions in terms of both pricing and duration continue to mitigate sovereign risks, weaker than expected macroeconomic conditions may bring underlying fiscal vulnerabilities to the fore again. In fact, public finances remain fragile in a number of countries. Looking ahead, waning fiscal consolidation efforts, particularly in combination with higher long-term interest rates as a result of a sudden sovereign risk repricing or deteriorating macroeconomic conditions, may pose a challenge to the sustainability of public finances. The materialisation of any of these risks may reignite concerns regarding public debt sustainability in the more vulnerable euro area countries.

Box 2

Policy uncertainty and the risk of market repricing

Policy uncertainty has remained elevated in recent years for the euro area and the broader global economy, at a time when the political landscape has become more fragmented. Political uncertainty has increased considerably since the global financial crisis in advanced economies (see Chart A, left panel). While political uncertainty is hard to capture in any single measure, heightened political fragmentation may complicate decision-making in national parliaments and could in certain instances potentially lead to policy instability. On this basis, a secular increase in the number of political parties during the past decades and a gradual decline in the voting share of the winning party suggests less cohesive political processes across constituencies (see Chart A, middle panel). Independent of the attribution of political uncertainty to an underlying cause, swings in policy uncertainty have grown in recent years, with trade policy uncertainty gaining prominence due to growing trade protectionism (see Chart A, right panel).

Chart A

Various metrics indicate a high level of uncertainty amid increasing signs of political fragmentation

Political risk rating and geopolitical risk index (left panel), number of political parties per election and voting share of winning party in the European Union (middle panel) and news-based measures of economic policy uncertainty (right panel)

(left panel: 2005-18, index points; middle panel: 1950- 2019, five-year moving averages; right panel: Jan. 2004-Apr. 2019, index points, six-month moving averages)

Sources: International Country Risk Group (ICRG), Caldara and Iacoviello (2017), Baker, Bloom and Davis (2013) and ParlGov database.

Notes: Left panel: the political risk rating is a synthetic index from ICRG measuring variables such as political unrest and the presence of conflicts, government stability, the investment climate, corruption, the rule of law and the quality of bureaucracy. For ease of exposition, the original index from the ICRG has been inverted so that an increase in the index indicates greater political risk. For the geopolitical risk index, see Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M., “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, working paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board, November 2017. Middle panel: European and parliamentary elections in the 28 current EU Member States (up until April 2019). Right panel: measures of economic policy uncertainty are taken from Baker, S., Bloom, N. and Davis, S., “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty”, Chicago Booth Research Paper No 13/02, January 2013.

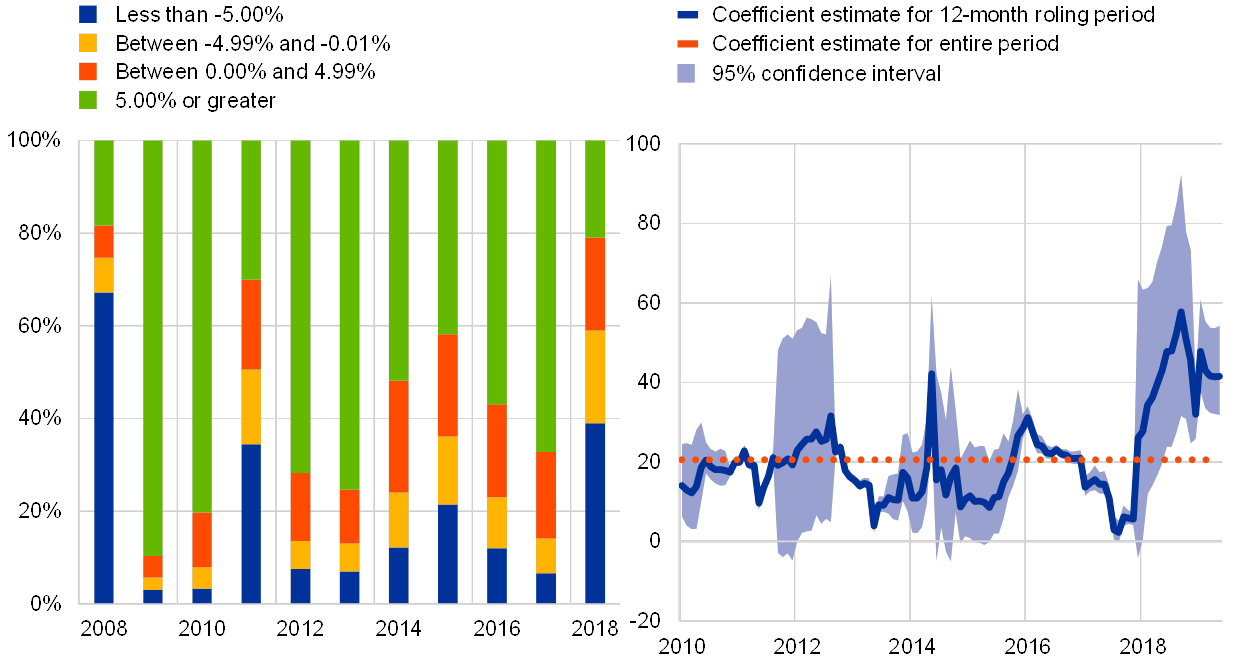

Policy uncertainty may lead to market concerns about sovereign debt sustainability amid still fragile fundamentals for many sovereigns. Policy uncertainty can have an impact on economic and financial outcomes (see Chart B). More uncertainty about future policy decisions may affect market perceptions of sovereign risk, with system-wide implications if fiscal or economic vulnerabilities weaken the sustainability of public debt. Financial markets tend to have considerable difficulty in pricing event risk, often leading to spikes in risk pricing when event risk materialises. Such changes in market sentiment can have significant impacts on sovereign debt sustainability. Three elements may explain the extent to which risk repricing in credit insurance against sovereign default may occur. First, fiscal fundamentals are key in determining vulnerability to sovereign debt sustainability concerns – most notably the stock of public debt relative to GDP. In fact, a high level of debt is a necessary condition for debt sustainability concerns to arise. Second, economic risk can govern the extent to which weaker growth can unearth concerns about these underlying fiscal fundamentals, and challenge debt sustainability. Such economic risk can be captured by variables, such as fiscal and current account balances, as well as economic growth and inflation. Third, political uncertainty can further exacerbate debt sustainability concerns, including not only traditional factors such as political unrest and the presence of conflicts, but also government stability, the investment climate, corruption, the rule of law and institutional quality.

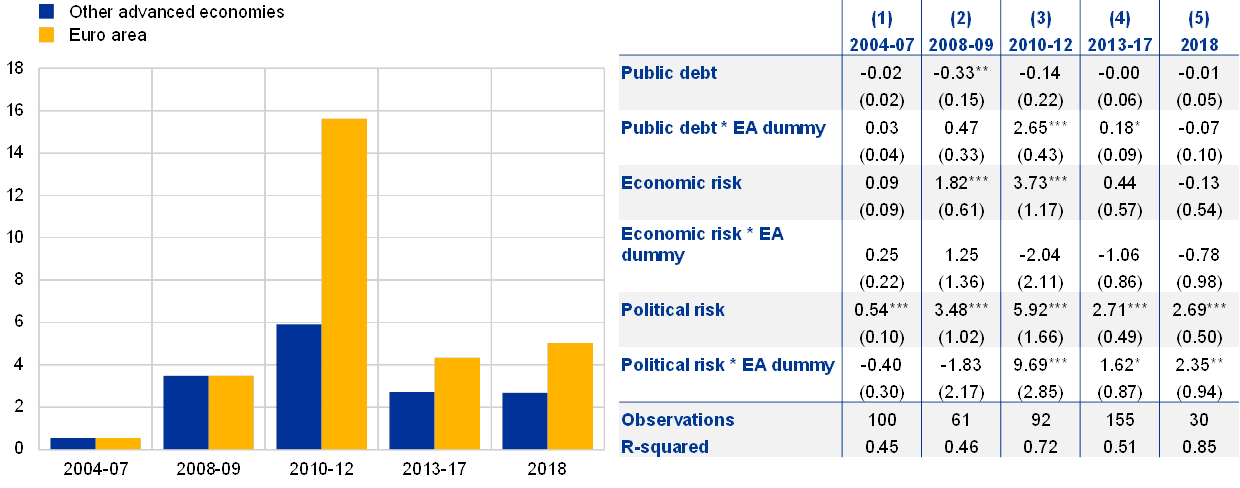

Chart B

Policy uncertainty can trigger sovereign debt sustainability concerns

Interlinkages between policy uncertainty and sovereign debt sustainability concerns

Source: ECB.

A simple analysis of this interaction of fiscal, economic and political uncertainty explains the considerable variation in market perceptions of sovereign creditworthiness. An examination of the price of insurance against sovereign credit risk across 30 advanced economies offers two main takeaways. First, the impact of political risk on credit default swap (CDS) spreads across all advanced economies examined was limited before the global financial crisis, but increased strongly in 2010-12 as market concerns about euro area sovereign indebtedness gained prominence. While lower compared with its peak in 2010-12, the sensitivity of CDS spreads to political uncertainty has remained higher than before the crisis in recent years (see Chart C).[11] Second, CDS spreads in euro area economies seem to be more sensitive to political uncertainty than in other advanced economies. This finding may reflect market concerns about the incompleteness of the institutional framework of the monetary union in combination with the sustainability of public debt in some euro area economies. Such concerns were particularly evident at the height of the euro area sovereign debt crisis in 2010-12, when sovereign CDS markets put an additional premium on political uncertainty, as well as public debt, for euro area economies compared with other advanced economies.

Chart C

Euro area CDS markets have been sensitive to political uncertainty since the sovereign debt crisis

Impact of political uncertainty on CDS spreads between 2004 and 2018

(left panel: CDS spreads, basis points; right panel: complete regression results)

Sources: Bloomberg, ICRG and ECB calculations.

Notes: The chart shows the estimated impact of political uncertainty on CDS spreads for 30 advanced economies between 2004 and 2018. In particular, the chart in the left panel shows the increase in CDS spreads, in basis points, corresponding to a one-unit increase in the political risk index. The model controls for the impact of economic fundamentals and the presence of outliers (right panel). Political risk is a synthetic index from ICRG comprising variables such as political unrest and the presence of conflicts, government stability, the investment climate, corruption, the rule of law and the quality of bureaucracy. Economic risk is a synthetic index from ICRG including the following variables: real GDP growth, inflation, fiscal deficit, current account deficit and GDP per capita. The original ICRG indices have been inverted so that an increase in the index indicates greater political or economic risk.

While political disagreement is a natural part of the democratic process, strong political fragmentation can lead to policy uncertainty. From a financial stability perspective, one potentially destabilising aspect of this uncertainty is the perception of debt sustainability for highly indebted sovereigns. Based on past experience, the sensitivity of sovereign risk premia to fundamentals in euro area economies could potentially increase in the case of a repricing of risk in global bond markets, thereby underscoring the need for consistent, clear and credible policies underpinning public finances.

1.3 Euro area households resilient, but some country-level vulnerabilities prevail

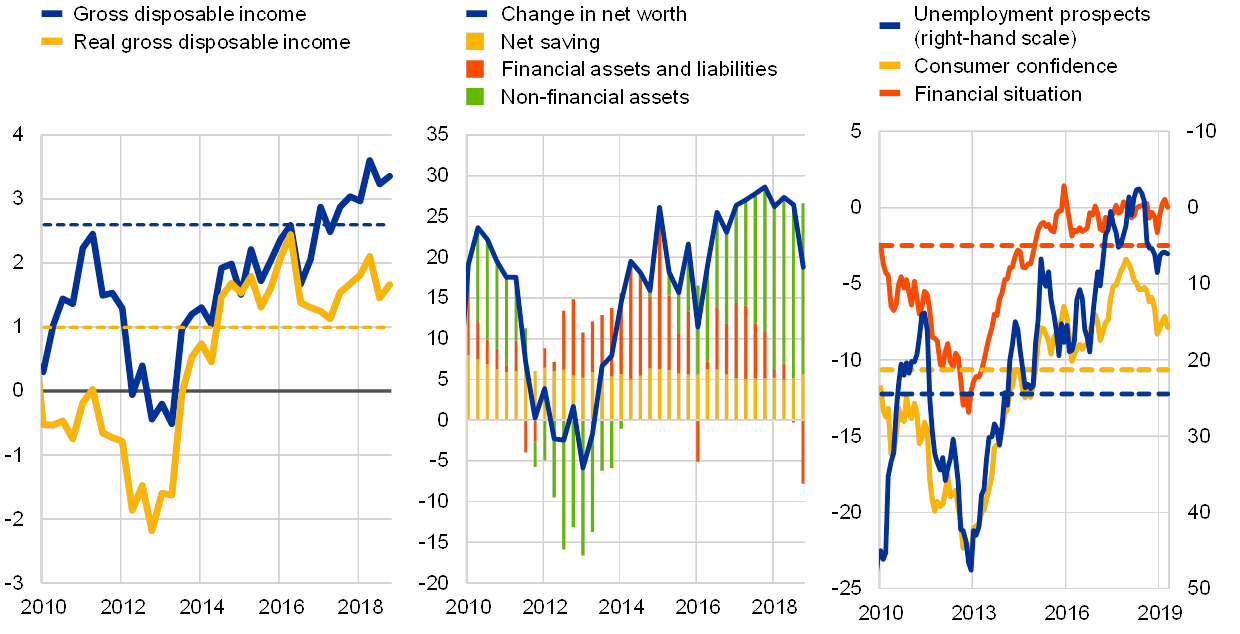

Euro area households’ income position has so far been fairly resilient to the slowdown in economic activity. Households’ real and nominal gross disposable income growth remained above long-term average rates in 2018 (see Chart 1.8, left panel) primarily bolstered by further improvements in labour market conditions and the related robust growth in labour income. Despite slowing towards the end of the year on account of losses on financial assets due to the correction in global stock markets, growth in household net worth remained solid throughout 2018 buttressed by valuation gains on property holdings amid sustained housing market momentum (see Chart 1.8, middle panel, and Section 1.5). Despite some deterioration over the course of 2018, households remain confident about their financial situation and unemployment prospects, consistent with the relatively robust consumer confidence (see Chart 1.8, right panel).

Chart 1.8

Income risks for euro area households have remained contained so far, while household confidence and sentiment started to recover in early 2019

Gross disposable income growth (left panel), change in the net worth of euro area households (middle panel), as well as consumer confidence and euro area households’ expectations about their financial situation and unemployment prospects (right panel)

(left panel: Q1 2010-Q4 2018, annual percentage changes; middle panel: Q1 2010-Q4 2018, four-quarter moving sums, percentage of gross disposable income; right panel: Jan. 2010-Apr. 2019, percentage balances)

Sources: European Commission, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the dashed horizontal lines represent the long-term averages, covering the period from Q2 2000 to Q4 2018. Middle panel: other flows in non-financial assets mainly include holding gains and losses on real estate (including land). Other flows in financial assets and liabilities mainly include holding gains and losses on shares and other equity, while changes in net worth due to net saving comprise net saving, net capital transfers received and the discrepancy between the non-financial and financial accounts. Right panel: unemployment prospects are presented using an inverted scale, i.e. an increase (decrease) of the indicator corresponds to more (less) optimistic expectations. The dashed horizontal lines represent the long-term averages covering the period from January 1985 to March 2019.

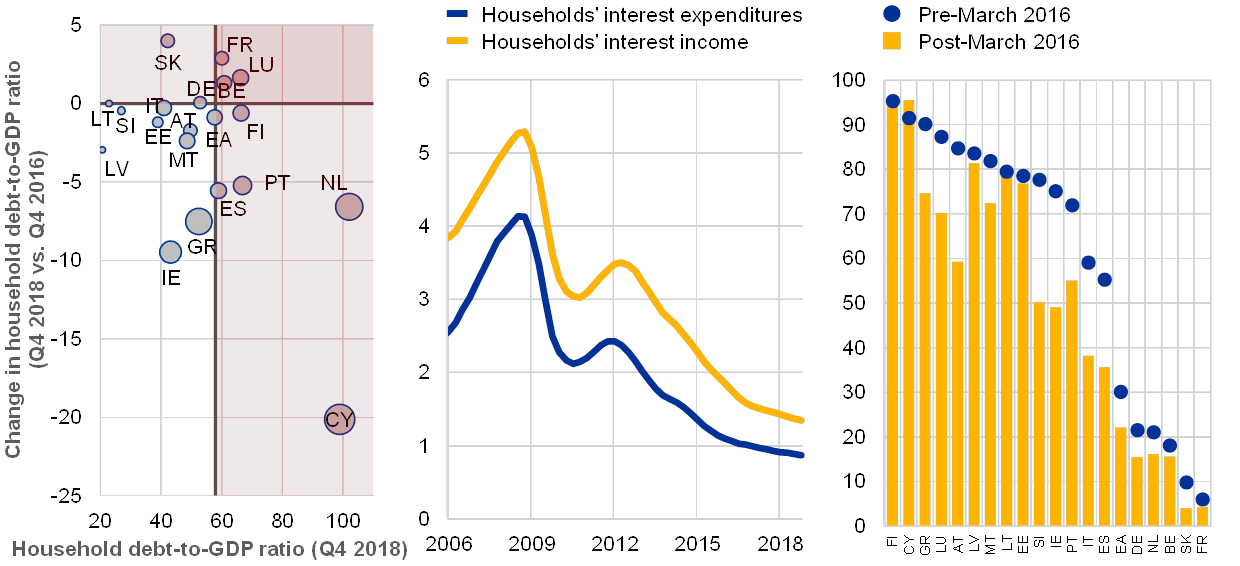

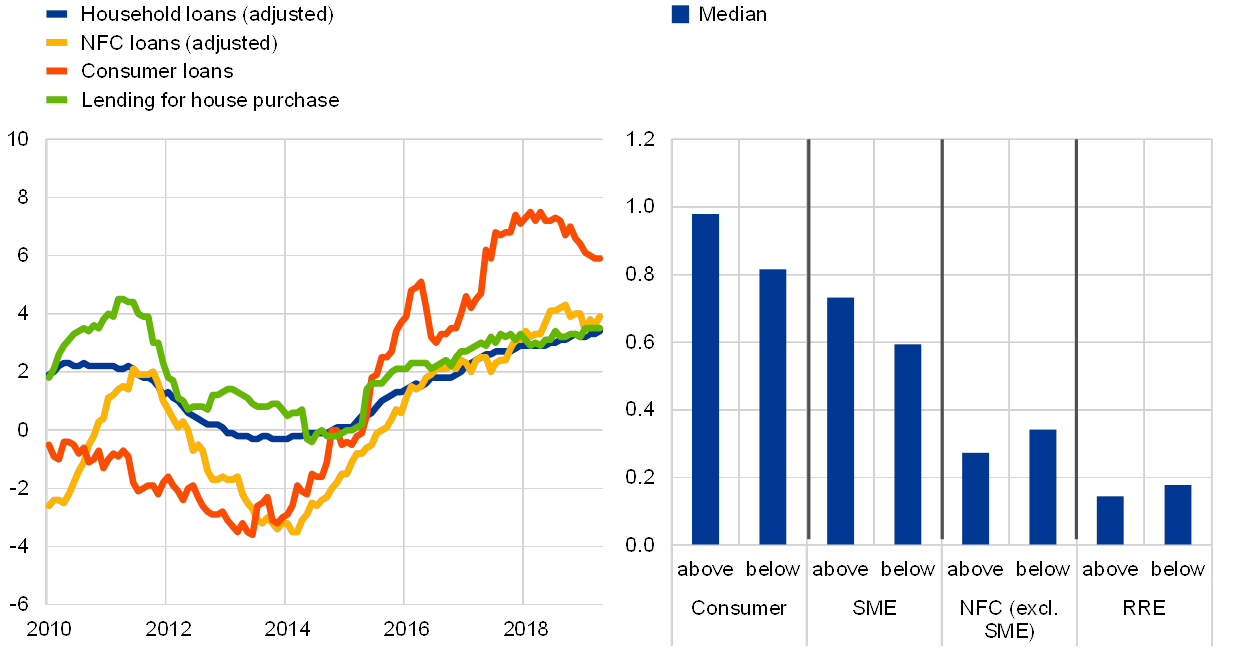

Household indebtedness has stabilised for the euro area as a whole, while remaining a cause for concern in some countries. On aggregate, the indebtedness of euro area households has stabilised at slightly below 58% of GDP in 2018 – a level that was last observed in early 2006 and is slightly below the estimated threshold associated with debt overhang based on the macroeconomic imbalance procedure. This figure is also relatively low by international standards. The euro area aggregate continues to mask a considerable degree of cross-country heterogeneity though, with the household debt-to-GDP ratio ranging from 21% in Latvia to slightly over 100% in the Netherlands. In terms of changes, there has been continued balance sheet repair (in both absolute and relative terms) in some euro area countries that were more affected by the crisis, e.g. Cyprus and Greece. Most other countries saw an increase in the absolute level of household debt over 2018, but only a few countries have seen debt grow faster than nominal GDP (see Chart 1.9, left panel).

Chart 1.9

While the interest payment burden remains low, elevated and rising household debt levels may represent a cause for concern in some euro area countries

Household debt-to-GDP ratios across the euro area (left panel), interest income and expenditure of euro area households (middle panel), as well as the share of new loans to households at a floating rate and with an interest rate fixation period of up to one year in total new loans (right panel)

(left panel: Q4 2018, Q4 2018 vs. Q4 2016, percentage of GDP, percentage point change in the debt-to-GDP ratio; middle panel: Q1 2006-Q4 2018, four-quarter moving sums, percentage of gross disposable income; right panel: percentages)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the size of the bubble indicates the country-specific debt service-to-income ratio. The bold vertical line represents the estimated macroeconomic imbalance procedure (MIP) benchmark of 58% of GDP for household debt. The 133% of GDP MIP benchmark for fully consolidated non-financial private sector debt is split between households and firms based on their average past shares in the stock of non-financial private debt. In the case of Ireland, GDP may not be the most representative scaling variable given the activities of foreign-owned multinational enterprises resident in the country. Alternative metrics that are more related to the domestic economy, such as modified gross national income (GNI*) or modified domestic demand, would yield considerably higher levels of household indebtedness. Right panel: loans to households comprise loans for house purchase, consumer lending and other lending. The pre-March 2016 period covers the three years before the last interest rate move by the Eurosystem (i.e. from April 2013 to March 2016), while the post-March 2016 period covers the time frame thereafter (i.e. from April 2016 to March 2019).

Debt sustainability concerns are mitigated by the low level of interest rates. A relatively resilient income position and improved net worth coupled with record low interest burdens bolster euro area households’ debt servicing capacity for the time being (see Chart 1.9, middle panel). The low interest rate environment has encouraged a shift towards longer rate fixation periods across countries. However, in the event of an interest rate shock without a commensurate boost to household income, more vulnerable households might be challenged going forward in countries where loans at floating rates or rates with rather short fixation periods predominate (see Chart 1.9, right panel). Continued balance sheet repair in countries with elevated levels of household debt should help mitigate the risks related to an eventual normalisation of interest rates and the ensuing rise in debt servicing costs, which are relatively high in some countries (see Chart 1.9, left panel).

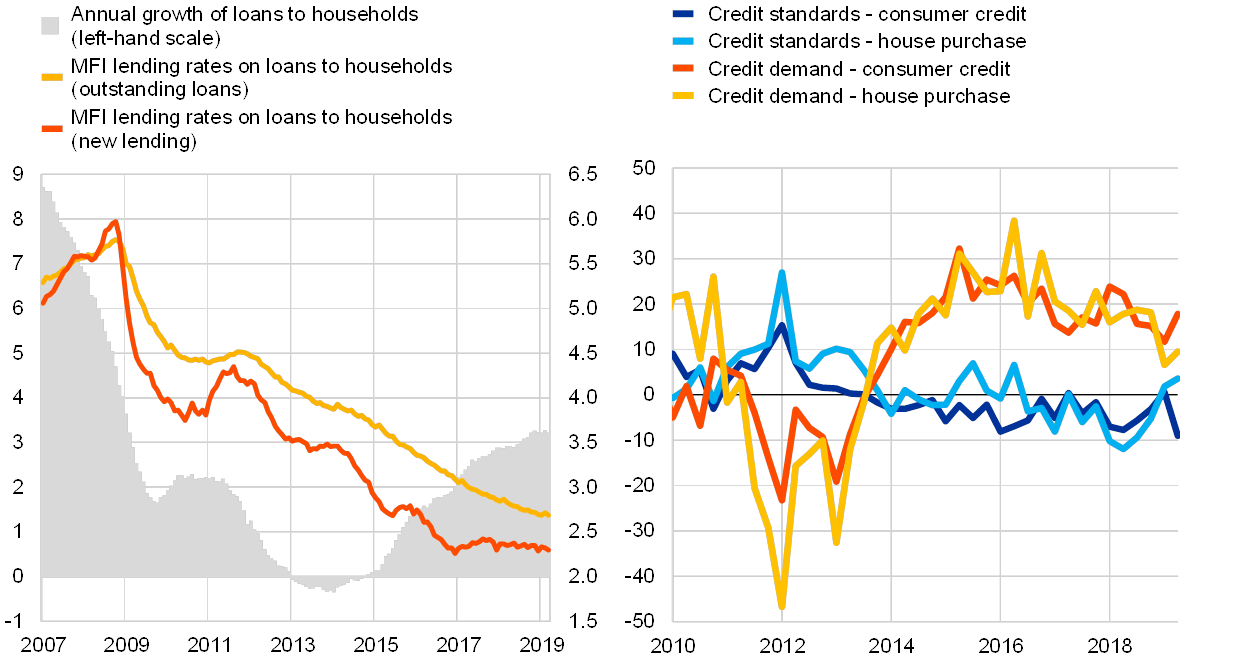

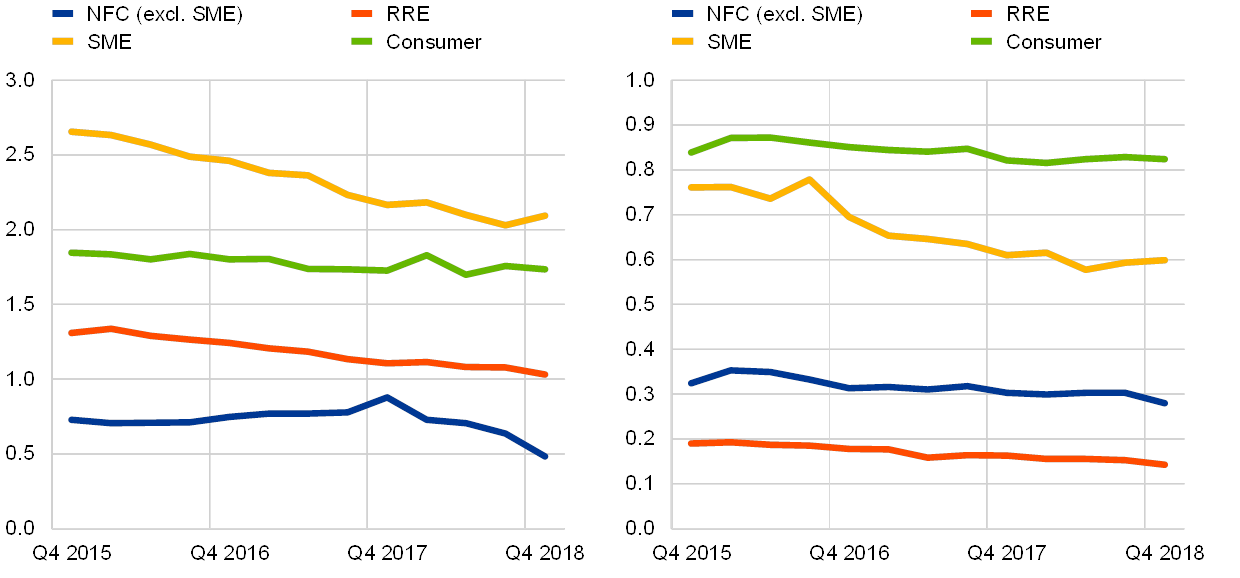

Lending flows to households stabilised at moderate levels, but underlying dynamics vary across countries and according to the purpose of lending. Overall, lending to euro area households continues to be supported by borrowing costs close to historical lows (see Chart 1.10, left panel), further improvements in labour market conditions and mature housing markets. At the country level, lending growth remained lacklustre in some countries (e.g. Cyprus, Greece and Latvia), while in others, such as Slovakia, Malta and Lithuania, household credit expanded briskly. Looking at the different lending types, consumer credit remains the most dynamic component of loans to households, but its pace of expansion has decelerated as consumption of (highly cyclical) durables has slowed and supervisory scrutiny has increased. Loans to households for house purchase continued to expand at a moderate pace. Going forward, banks expect weaker demand and tighter supply conditions for loans for house purchase than for consumer credit (see Chart 1.10, right panel).

Chart 1.10

Bank lending to euro area households is supported by lending rates close to historical lows, but demand and supply conditions have tightened more recently

Annual growth in household loans and MFI lending rates on new lending and outstanding loans to euro area households (left panel), as well as credit standards and demand for household loans by type of credit (right panel)

(left panel: Jan. 2007-Mar. 2019, annual percentage changes, percentages; right panel: Q1 2010-Q2 2019, weighted net percentages, three-month expectations)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

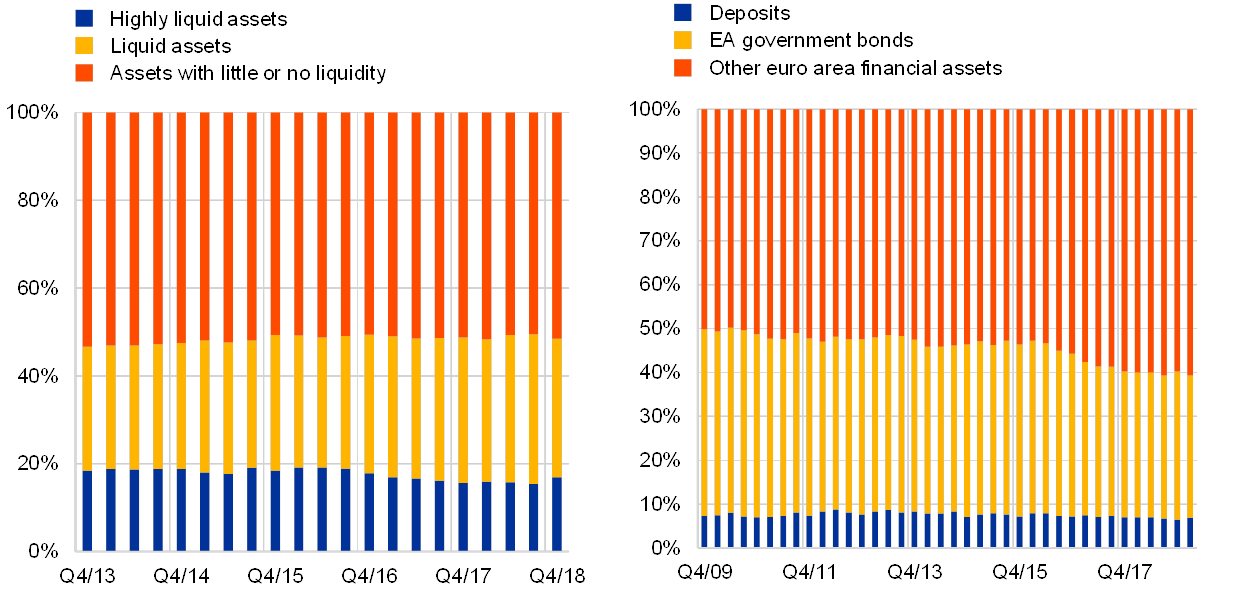

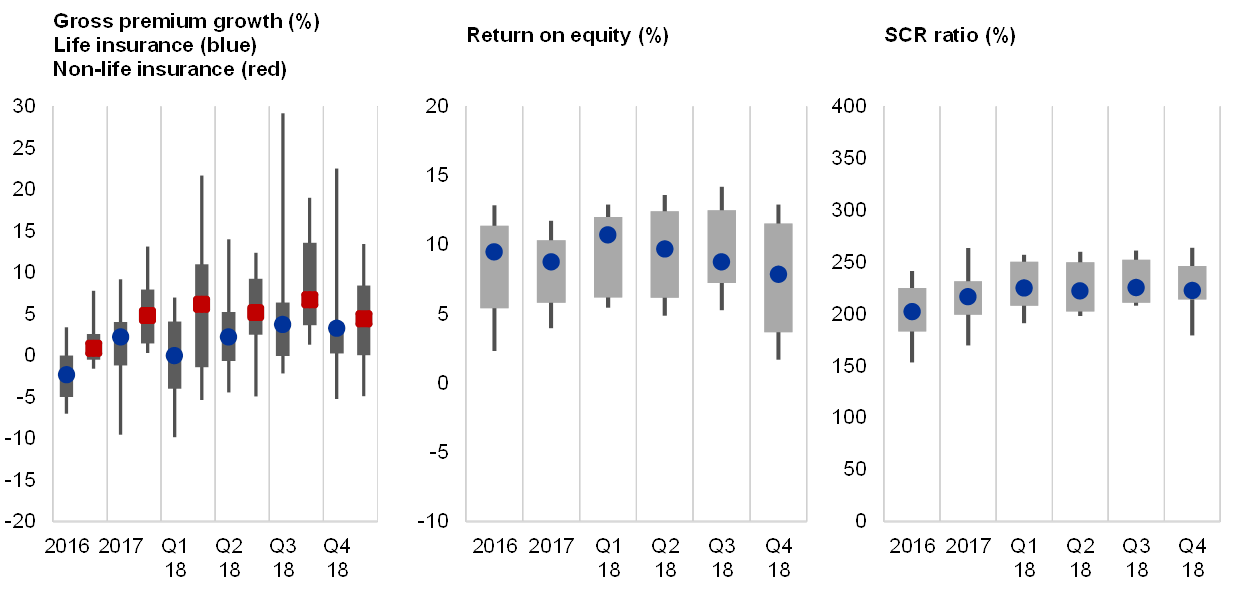

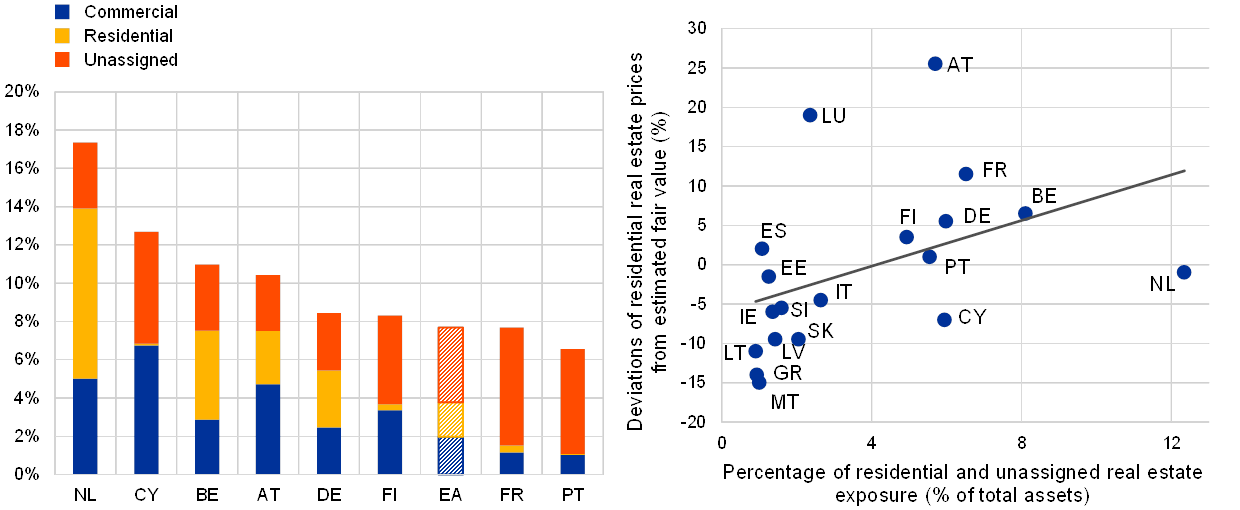

Notes: Left panel: loans are adjusted for loan sales and securitisation. Right panel: credit demand indicates the net percentage of banks reporting a positive contribution to demand, while credit standards refer to the net percentage of banks contributing to a tightening of credit standards. A negative (positive) number for credit standards represents an easing (tightening).