Published as part of the Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area 2024

The EU FinTech industry has grown significantly since the mid-2010s. Broadly speaking, financial technology companies (FinTechs) are firms that use technology to provide innovative financial services solutions.[1] The FinTech industry has been growing in the EU at a very rapid pace since 2016, with more than twice as many new FinTechs being established in the EU since then than in the previous 15 years (Chart A). While FinTechs are located across the EU, the map in Chart A shows that they tend to cluster in larger financial centres.[2] This box identifies the EU locations in which FinTechs have tended to establish themselves and concludes that, while there are other possible factors at play, geographical proximity to financial centres supports FinTech activity in a number of ways. These include easier access to equity financing, opportunities to tap into a diversified pool of fundings tailored to FinTechs’ risk profiles and development stages and the availability of institutional support schemes.

Notwithstanding certain risks,[3] FinTechs can bring considerable benefits to both the financial sector and the broader economy, including consumers. FinTech firms can improve access to finance for businesses and households, which is vital for economic growth.[4] By introducing advanced technological solutions, FinTechs carry transformation risks but they can also enhance the quality and efficiency of financial services. In fact, many European banks maintain collaborations with FinTechs to enhance their service offerings.[5] This benefits FinTech customers by offering them a wider range of options and greater diversification of financial products and services, as well as lowering the costs associated with financial transactions and services, thereby enhancing competition.[6]

Chart A

Where Fintech choose to locate in the EU

Sources: Crunchbase, ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The sample included all FinTech firms reported in the Crunchbase database with a head office in the EU, excluding companies that self-identified as crypto-asset providers or insurance technology (InsurTech) firms over the period from 2000 to 2023. The left-hand chart is based on a sample of 7,811 companies over the period from 2000 to 2015. The right-hand chart is based on a sample of 19,548 companies over the period from 2016 to 2023.

In the light of the significant potential benefits of FinTech for the economy and consumers in general, the rapid growth of the EU FinTech industry has been accompanied by significant policy efforts. As part of the broader capital markets union (CMU) agenda, the European Commission launched a FinTech Action Plan[7] in 2018 to foster a more competitive and innovative European financial sector and to enhance integration. Furthermore, the launch of the EU Digital Finance Platform[8] and the adoption of additional legislation, such as the proposed financial data access and payments package[9], are deemed by the European Commission to be instrumental in fostering an environment conducive to FinTech growth. This includes efforts to develop an EU open finance framework and the Regulation on European Crowdfunding Service Providers[10], both of which are aimed at bolstering the European FinTech ecosystem.[11]

These initiatives at the EU level are complemented by numerous actions at national and subnational level that are aimed at encouraging the establishment and growth of FinTechs. Of particular note in this regard is the emergence of institutional support schemes in the form of regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs, as well as incubator and accelerator programmes, many of which are specifically designed for FinTechs. While such innovation hubs or sandboxes mainly provide a forum for exchange and advice, incubators and accelerators may also involve financial support to participating businesses.[12]

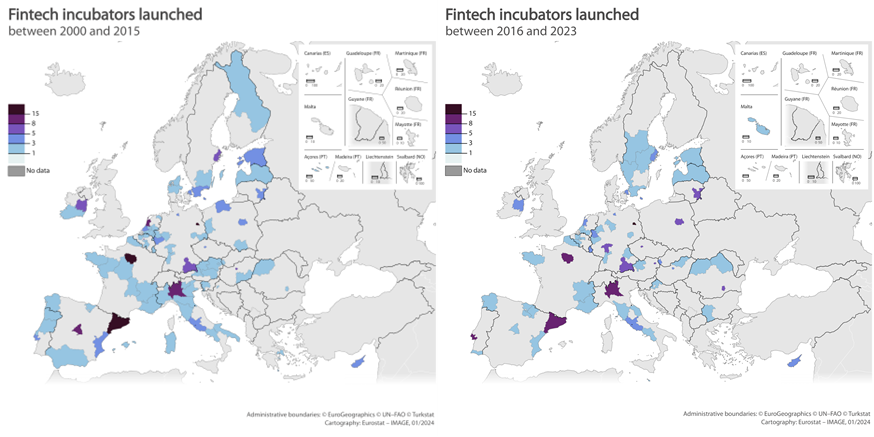

FinTech incubators have been launched across EU regions since the early 2000s, and increasingly so since the mid-2010s (Chart B). In line with the general trend in this segment, FinTech incubators are predominantly concentrated in financial centres such as Berlin, Milan, and Paris. However, the effectiveness of such incubators is hard to assess owing to the absence of centralised and verified information on their activities. Despite this, the available data show that many European FinTechs have received funding directly from incubators, although typically only small amounts.[13] Furthermore, the more extensive support provided by both incubators and accelerators not only assists with initial funding but also potentially enhances the visibility and credibility of FinTechs, facilitating their access to additional funding from third-party sources.[14]

Chart B

The FinTech incubator landscape in the EU

Sources: Crunchbase, ECB staff calculations.

Notes: A sample of 941 incubators in EU countries was compiled. Of this sample, 426 were further identified as FinTech incubators (excluding those that are crypto-focused) and are displayed on the maps above based on their launch date. The sample does not provide a comprehensive snapshot of FinTech incubators in the EU. The left-hand chart is based on a sample of 248 incubators over the period from 2000 to 2015. The right-hand chart is based on sample of 178 incubators over the period from 2016 to 2023.

FinTechs are not spread homogenously across the EU, but tend to cluster in financial centres. 53% of all the EU FinTechs in the sample are located in a financial centre (Chart A). This is consistent with evidence suggesting that countries with more developed financial centres experience higher relative rates of FinTech formation.[15] Additionally, research shows that FinTechs are geographically clustered and that the location of new FinTech startups is affected by the size of these clusters and the presence of incubators.[16] Larger clusters attract more new FinTech startups, and incubators are shown to amplify this effect.[17]

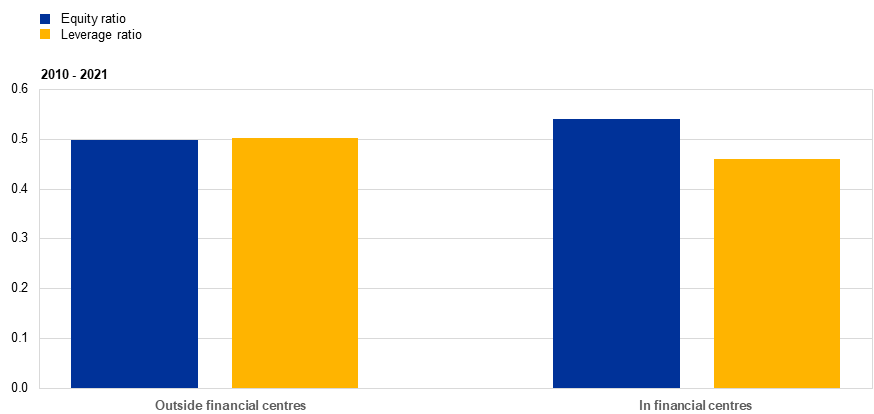

The analysis suggests that one of the reasons for the clustering of FinTechs close to financial centres may be easier access to equity finance. FinTechs are known to rely on equity funding[18] given their high level of intangibles and greater risk compared with established firms and business lines, and given their ambition to grow.[19] A desire to avoid debt in their early stages and the benefits of having investors as strategic partners are also likely to play a role. To check whether the choice of location may indeed correlate with differences in access to equity financing, we constructed a novel dataset of EU FinTechs[20] and assessed the changes in their average equity and debt financing (i.e. their funding mix) over time. We found that EU FinTechs do indeed rely heavily on equity funding and that those in the sample that were located close to financial centres generally had a higher share of equity financing than those that were not (Chart C). The underlying data further suggest that this difference has grown over time.

Chart C

Leverage and equity ratios for FinTechs domiciled in financial centres and non-financial centres

Sources: Bureau Van Dijk Orbis, Crunchbase, ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The analysis covered EU-based FinTechs that offer solutions in the areas of payments, digital banking, credit and capital raising, investment, advisory and asset management, or that provide technology solutions to financial and non-financial firms. FinTechs providing services that foster the development of a FinTech-enabling environment (i.e. insurance technology (InsurTech), regulatory technology (RegTech) companies) also fell within the scope of this analysis. Crypto-asset providers, BigTechs offering financial services and banking institutions developing technology solutions were not covered by the analysis. This chart shows the FinTechs captured in both the Crunchbase and Bureau van Dijk Orbis databases for which the balance sheet data required for the analysis was available. Consequently, this chart does not represent a full population sample of EU FinTechs. The equity ratio is measured as the ratio of total equity over total assets. The leverage ratio is measured as total debt over total assets. The ratios given are averages. Financial centre denotes a city qualifying as one of the top 50 global financial centres according to the Global Financial Center Index.

Regression analysis further suggests that FinTechs in a financial centre may generally be subject to less scrutiny by equity investors than those located at a greater physical distance from financial hubs. Pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were performed on the unbalanced panel dataset, further dividing the sample between FinTechs located in financial centres and those that were not. In the sample, a firm’s performance, measured as the return on assets (RoA), only played a significant role in FinTech equity and leverage financing for companies located outside financial centres (Table A). This suggests that FinTechs closer to financial centres generally have easier access to equity funding, possibly owing to the synergies that come from being located in larger clusters, such as a concentration of investors and a reduction in the risk of failure.[21] The results suggest that FinTechs outside financial centres need to rely more on their performance as a signalling device to potential funding providers. Moreover, the academic literature suggests that the risk of failure is significantly lower for FinTech startups that have been developed in an incubator, and incubators tend to be located disproportionately in financial centres.[22]

Table A

Impact of past performance on FinTech funding mix depending on location

(estimates)

Financial centres: | Financial centres: | Non-financial centres: equity ratio | Non-financial centres: leverage ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

RoA(t-1) | 0.000511 (0.000545) | -0.000471 (0.000545) | 0.00175*** (0.000568) | -0.00175*** (0.000568) |

Overall R2 | 0.0987 | 0.106 | 0.101 | 0.101 |

Number of observations | 556 | 549 | 558 | 558 |

Sources: Bureau Van Dijk Orbis, Crunchbase, ECB staff calculations.

Notes: RoA stands for return on assets. R2 stands for R squared. The estimates result from ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions run for firms located in financial centres and non-financial centres across the sample of firms with matched Crunchbase and Bureau van Dijk Orbis data. The dependent variables were the equity and leverage ratios (expressed in percentage points), while independent variables included RoA (income based and in percentage points), total assets (in real terms and log scale), firm age and cash ratio (cash and cash equivalents divided by current liabilities), as well as the GDP growth in the previous year for the country concerned. The estimation also included firm and year-based fixed effects. Sample: 2010-2021 for the Member States of the EU. Standard errors in parenthesis. * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.001.

Overall, the analysis highlights the importance of financial centres for FinTechs and points to the need for further examination of the role and effectiveness of institutional support schemes. The findings underline the importance of completing the CMU agenda, in particular as regards policy efforts to grow European equity markets, in terms of both liquidity and depth. Institutional support schemes could complement this agenda by further bolstering targeted financing for innovation, in particular by facilitating, inter alia, FinTech access to financing at the early stages of their development and later developing a sustainable business model.

While precise definitions differ, the Financial Stability Board has, for instance, defined FinTech as "technology-enabled innovation in financial services that could result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on the provision of financial services” – Financial Stability Board, FinTech and market structure in financial services: Market developments and potential financial stability implications, 4 February 2019.

We define EU financial centres as cities (and their associated regions, based on the nomenclature of territorial units for statistics: level 2 (NUTS2)) that were classified as being among the global top 50 cities in the 33rd edition of the Global Financial Centres Index, published by the Z/Yen Partners in collaboration with the China Development Institute. The EU cities falling into this category are Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Copenhagen, Dublin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Helsinki, Luxembourg, Madrid, Milan, Munich, Paris, Stockholm and Stuttgart.

While this box highlights the manifold potential benefits of FinTech that have prompted support schemes, including those with public-sector involvement, any innovation, including FinTech, clearly also entails risks. For example, for FinTech, the risks may relate to consumer protection and privacy, regulatory arbitrage, operational risk linked, among others, to digitalisation and outsourcing, and potentially also risks to financial stability, if FinTechs eventually became significant in size and scale.

There are different strands of literature that document the benefits of FinTech. First, the literature that focuses on the potential of FinTech to transform banking business models (see Bertsch, C. and Rosenvinge, C. J., “Fintech credit: Online lending platforms in Sweden and beyond,” Economic Review, Issue 2, Sveriges Riksbank, 2019, pp. 42-70; Buchak, G., Matvos, G., Piskorski, T. and Seru, A., “Fintech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 130, Issue 3, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 453-483). Second, the literature showing the benefits of FinTech in boosting the real economy; for example, FinTech lenders increased their lending to small businesses after the 2008 global financial crisis and played an important role in the recovery (see Gopal, M. and Schnabl, P., “The rise of finance companies and fintech lenders in small business lending“, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 35, Issue 11, Oxford Academic, November 2022, pp. 4859-4901; Berg, T., Fuster, A. and Puri, M., “FinTech Lending”, Annual Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 14, November 2022, pp. 187-207).

Beck, T. et al., “Will video kill the radio star? – Digitalisation and the future of banking”, Reports of the Advisory Scientific Committee, European Systemic Risk Board, No 12, January 2022.

The literature highlighting the potential for innovation includes, for example, Chen, M. A., Wu, Q. and Yang, B., “How valuable is FinTech innovation?”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 32, Issue 5, Oxford Academic, May 2019, pp. 2062-2106.

See the European Commission communication of 8 March 2018 entitled “FinTech Action plan: For a more competitive and innovative European Financial sector” (COM(2018) 109 final).

“The EU Digital Finance Platform is a collaborative space bringing together innovative financial firms and national supervisors to support innovation in the EU’s financial system. This platform offers practical tools designed to facilitate the scaling up of innovative financial firms across the EU. […] [It] features a Data Hub, cross-border services, a fintech mapping, an overview of the latest policy news, calls to action and events. […] [The] Data Hub will make available to participating firms specific sets of non-public, non-personal data, with a view to enable them to test innovative products and train AI/ML models”– see the page entitled “EU Digital Finance Platform" on the European Commission website.

For more information, see the European Commission Financial data access and payments package website.

Regulation (EU) 2020/1503 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 October 2020 on European crowdfunding service providers for business, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 and Directive (EU) 2019/1937 (OJ L 347, 20.10.2020, p. 1).

Other notable initiatives include the EBA include the EBA's FinTech Knowledge Hub established in 2018.

Innovation hubs are schemes through which entities can interact with competent authorities and seek “guidance on the conformity of innovative financial products, services, business models or delivery mechanisms with licensing, registration and/or regulatory requirements” (see EBA, EIOPA and ESMA, Report – FinTech: Regulatory sandboxes and innovation hubs, 9 January 2019), whereas regulatory sandboxes are schemes in which participating businesses can test within a controlled environment innovative services, products or business models, subject to monitoring by the competent authority. By contrast, incubators or accelerators tend to be private-led initiatives, possibly with government support, and provide a much wider range of services to participating entities, ranging from infrastructure over contacts to financing. The terms incubators and accelerators are often used interchangeably, although incubators tend to be geared towards early-stage start-up firms while accelerators tend to focus on later stage firms. For more details on the functioning of innovation facilitators, innovation hubs and sandboxes, see EBA, EIOPA and ESMA, Report – Update on the functioning of innovation facilitators – innovation hubs and regulatory sandboxes, 11 December 2023.

FinTech incubators were identified based on the sectoral categories used in the Crunchbase database. In addition, Incubators matched as FinTech investors in the Bureau Van Dijk Orbis sample were also taken into consideration. Of the 425 FinTech incubators in EU countries (excluding those with a cryptographic focus) identified in the Crunchbase database, 144 incubators participated in at least one funding round for one of the FinTechs in the sample for this analysis.

For an overview on the role of incubators and accelerators for FinTech financing, see Griol-Barres, I. and Morant-Martinez, O., “The Role of Incubators and Accelerators in Entrepreneurial Fundraising”, in Sendra-Pons, P., Garzon, D. and Revilla-Camacho, MÁ. (eds), New Frontiers in Entrepreneurial Fundraising. Contributions to Finance and Accounting, Springer International Publishing, 2023.

See Laidroo, L. and Avarmaa, M., “The role of location in FinTech formation”, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, Vol. 32, Issue 7-8, 2020, pp. 555-572, in which the authors measure FinTech formation rates relative to the size of the labour force.

See, for example, Gazel, M. and Schwienbacher, A., “Entrepreneurial fintech clusters”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 57, Springer International Publishing, 26 March 2021, pp. 883-903.

Ibid.

The literature on the financing of FinTechs provides a mixed picture, depending, among others, on the stage of development, asset structure and type of FinTech activity. For example, Cornelli et al., “Regulatory Sandboxes and Fintech Funding: Evidence from the UK”, Review of Finance, Vol. 28, Issue 1, January 2024, pp. 203–233, show that FinTechs benefit from regulatory sandboxes in accessing venture capital financing in the early stages of their development. Looking at the types of financing used in the three years following incorporation, the literature finds that unregulated FinTech start-ups are more likely to be financed with long-term debt and that FinTechs that receive equity financing receive less long-term debt funding – see Giaretta, E. and Chesini, G., “The determinants of debt financing: The case of fintech start-ups”, Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, Vol. 6, Issue 4, Science Direct, October-December 2021, pp. 268-279.

For a review of the literature on FinTech financing channels and conditions, see Bollaert, H., Lopez-de-Silanes, F. and Schwienbacher, A., “Fintech and access to finance”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 68, Elsevier, June 2021, pp. 101941. The funding gap is highlighted in Wilson, N., Wright, M. and Kacer, M., “The equity gap and knowledge-based firms”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 50, Elsevier, June 2018, pp. 626-649. More specifically, seed funding is scarce, translating into large funding gaps for startups and later-stage ventures (ibid). In addition, the traditional equity and debt funding channels have proven to have substantial challenges, leaving small firms with insufficient finance (Lopez-de-Silanes, F., McCahery, J., Schoenmaker, D. and Stanisic, D., “Estimating the Financing Gap of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises”, Journal of Corporate Finance Research, Vol. 12, No. 2, July 2018, pp. 7-130).

A sample of FinTechs was identified through data made available by the Crunchbase platform. Data from the Bureau Van Dijk Orbis database – a global dataset containing company information – was used to obtain firm-by-firm annual balance sheet information for those FinTechs, excluding those entities classified as banks or non-bank financial intermediaries. This sample was further refined by excluding information and communication technology (ICT) service providers and traditional financial service providers. Given that there are no official statistics on the size of the EU FinTech sector and no harmonised definition, the actual proportion of the total EU FinTech universe captured in the sample could not be ascertained nor could it be determined the extent to which the sample is representative of the EU FinTech sector as a whole.

See, for example, Gazel, M. and Schwienbacher, A., “Entrepreneurial fintech clusters“, Small Business Economics, Vol. 57, Springer International Publishing, 26 March 2021, pp. 883-903.

The analysis was aimed at checking whether FinTechs close to financial centres were similar in type to those located further away and therefore whether the funding differed for firms with similar prospects.