Economic and monetary developments

Overview

At its monetary policy meeting on 10 September 2020, the Governing Council decided to keep its accommodative monetary policy stance unchanged. Incoming information suggests a strong – though incomplete ‒ rebound in activity broadly in line with previous expectations, although the level of activity remains well below the levels prevailing before the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. While activity in the manufacturing sector has continued to improve, momentum in the services sector has slowed somewhat recently. The strength of the recovery remains surrounded by significant uncertainty, as it continues to be highly dependent on the future evolution of the pandemic and the success of containment policies. Euro area domestic demand has recorded a significant recovery from low levels, although elevated uncertainty about the economic outlook continues to weigh on consumer spending and business investment. Headline inflation is being dampened by low energy prices and weak price pressures in the context of subdued demand and significant labour market slack. Against this background, ample monetary stimulus remains necessary to support the economic recovery and to safeguard medium-term price stability. Therefore, the Governing Council decided to reconfirm its accommodative monetary policy stance at its meeting on 10 September 2020.

Economic and monetary assessment at the time of the Governing Council meeting of 10 September 2020

The coronavirus pandemic remains the main source of uncertainty for the global economy. After a temporary stabilisation around mid-May, which led to a gradual lifting of containment measures, the number of daily new cases started picking up again more recently which has fuelled fears of a strong resurgence in coronavirus infections. These fears have been weighing on consumer confidence. Incoming data confirm that global economic activity bottomed out in the second quarter and started to rebound in line with the gradual lifting of containment measures from mid-May onwards. The September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections envisage that world real GDP (excluding the euro area) will contract by 3.7% this year and expand by 6.2% and 3.8% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The contraction in global trade will be more severe given both its strong procyclicality, especially during economic downturns, and the peculiar nature of the coronavirus crisis, which has entailed disruptions in global production chains and increased trade costs because of the containment measures. Risks to the global outlook remain skewed to the downside given the persistent uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic, which may leave lasting scars on the global economy. Other downside risks relate to the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, the risk of a rise in trade protectionism, and longer-term negative effects on global supply chains.

Although financial conditions in the euro area have loosened somewhat further since the Governing Council’s meeting in June 2020, they have not yet returned to the levels seen before the coronavirus pandemic. Over the review period (from 4 June to 9 September 2020), the forward curve of the euro overnight index average (EONIA) shifted slightly downwards and, although mildly inverted at the short end, it does not signal firm expectations of an imminent rate cut. Long-term euro area sovereign bond spreads decreased over the review period amid a combination of monetary and fiscal support. Prices of risky assets increased somewhat, mainly against the backdrop of a generally more positive short-term earnings outlook. In foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated relatively strongly in trade-weighted terms and against the US dollar.

Euro area real GDP contracted by 11.8%, quarter on quarter, in the second quarter of 2020. Incoming data and survey results indicate a continued recovery of the euro area economy and point to a rebound in GDP in the third quarter although remaining below pre-crisis levels. Alongside a significant rebound in industrial and services production, there are signs of a clear recovery in consumption. Recently, momentum has slowed in the services sector compared with the manufacturing sector, which is also visible in survey results for August. The increases in coronavirus infection rates during the summer months constitute headwinds to the short-term outlook. Looking ahead, a further sustained recovery remains highly dependent on the evolution of the pandemic and the success of containment policies. While the uncertainty related to the evolution of the pandemic will likely dampen the strength of the recovery in the labour market and in consumption and investment, the euro area economy should be supported by favourable financing conditions, an expansionary fiscal stance and a strengthening in global activity and demand.

This assessment is broadly reflected in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. These projections foresee annual real GDP growth at ‑8.0% in 2020, 5.0% in 2021 and 3.2% in 2022. Compared with the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for real GDP growth has been revised up for 2020 and is largely unchanged for 2021 and 2022. Given the exceptional uncertainty currently surrounding the outlook, the projections include two alternative scenarios, a mild one and a severe one, corresponding to different assumptions regarding the evolution of the pandemic.[1] Overall, the balance of risks to the euro area growth outlook is seen to remain on the downside. This assessment largely reflects the still uncertain economic and financial implications of the pandemic.

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, euro area annual HICP inflation decreased to ‑0.2% in August, from 0.4% in July. On the basis of current and futures prices for oil and taking into account the temporary reduction in the German VAT rate, headline inflation is likely to remain negative over the coming months before turning positive again in early 2021. Moreover, in the near term price pressures will remain subdued owing to weak demand, lower wage pressures and the appreciation of the euro exchange rate, despite some upward price pressures related to supply constraints. Over the medium term, a recovery in demand, supported by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, will put upward pressure on inflation. Market-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations have returned to their pre-pandemic levels, but still remain very subdued, while survey-based measures remain at low levels.

This assessment is broadly reflected in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which foresee annual inflation at 0.3% in 2020, 1.0% in 2021 and 1.3% in 2022. Compared with the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for inflation is unchanged for 2020, has been revised up for 2021, and is unchanged for 2022. The unchanged projection for inflation in 2022 masks an upward revision to inflation excluding energy and food – in part reflecting the positive impact of the monetary and fiscal policy measures – which was largely offset by the revised path of energy prices. Annual HICP inflation excluding energy and food is expected to be 0.8% in 2020, 0.9% in 2021 and 1.1% in 2022.

The coronavirus pandemic has continued to influence significantly monetary dynamics in the euro area. Broad money (M3) growth continued to rise, reaching 10.2% in July 2020, after 9.2% in June. The strong money growth reflects domestic credit creation, the ongoing asset purchases by the Eurosystem and precautionary considerations which foster a heightened preference for liquidity in the money-holding sector. The narrow monetary aggregate M1, encompassing the most liquid forms of money, continues to be the main contributor to broad money growth. Developments in loans to the private sector continued to be shaped by the impact of the coronavirus on economic activity. The annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations remained broadly stable in July, standing at 7.0%, compared with 7.1% in June. These high rates reflect firms’ elevated liquidity needs to finance their ongoing expenditures and working capital and to further build liquidity buffers, although the rebound in economic activity has resulted in some recovery in their revenues. The annual growth rate of loans to households also remained stable at 3.0% in July. The Governing Council’s policy measures, together with the measures adopted by national governments and European institutions, will continue to support access to financing, including for those most affected by the ramifications of the pandemic.

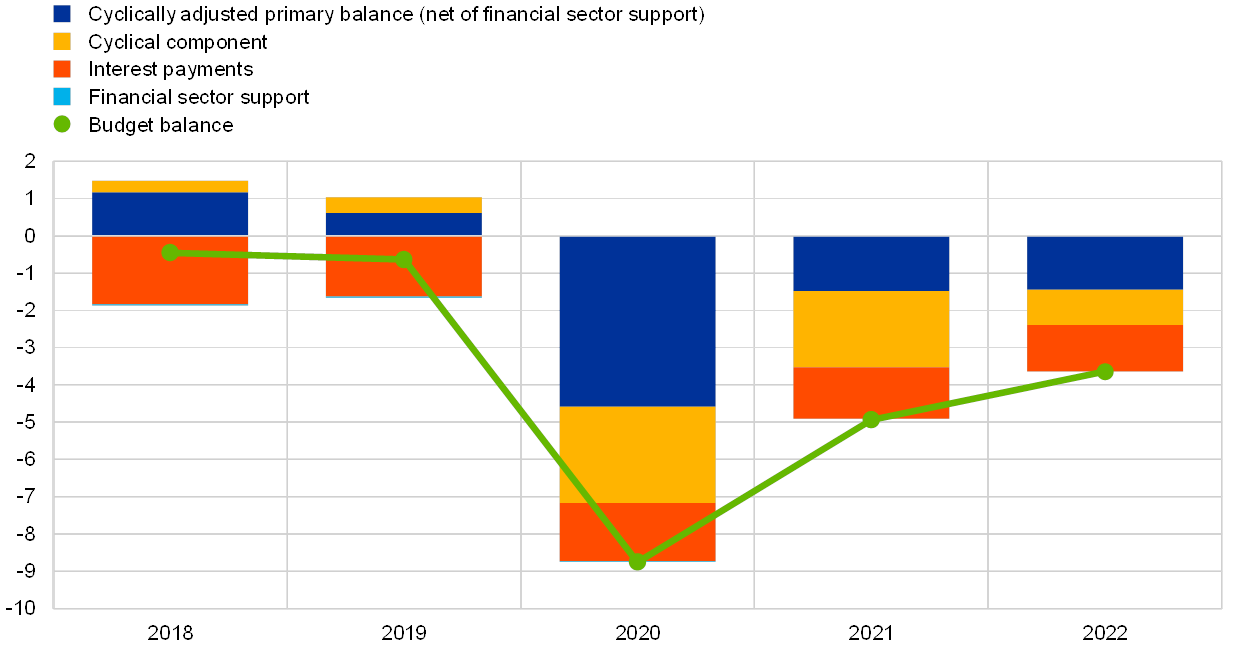

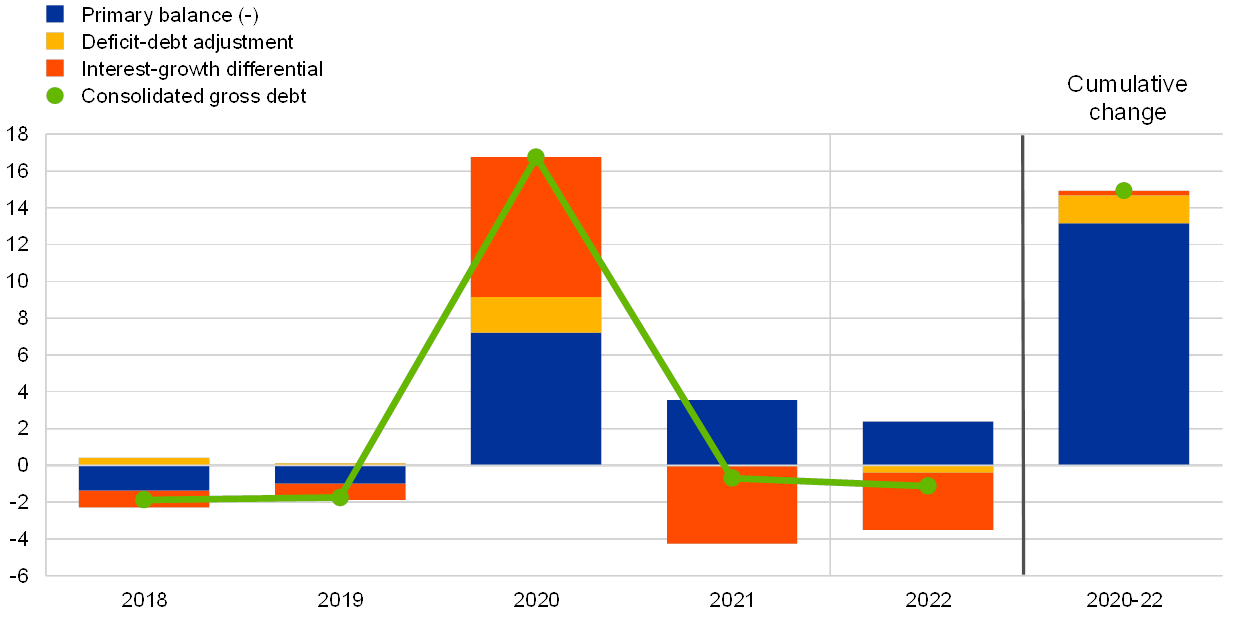

The coronavirus pandemic continues to have an extraordinarily large impact on public finances in the euro area. The fiscal cost of containment measures has been very substantial for all euro area countries, although both the burden and the capacity to respond vary across countries. As a result of the economic downturn and the substantial fiscal support, the general government budget deficit in the euro area is projected to increase significantly to 8.8% of GDP in 2020, compared with 0.6% in 2019. The deficit ratio is expected to decline to 4.9% and 3.6% of GDP in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The extensive fiscal measures in 2020 have led to a corresponding worsening of the cyclically adjusted primary balance, in addition to a negative cyclical component reflecting the deterioration in the macroeconomic situation. The subsequent improvement is expected to be led by the phasing-out of the emergency measures and a better cyclical situation. An ambitious and coordinated fiscal stance remains critical, in view of the sharp contraction in the euro area economy, although measures should be targeted and temporary. In this respect, both the €540 billion package of three safety nets endorsed by the European Council and the European Commission’s Next Generation EU package of €750 billion, which has the potential to significantly support the regions and sectors hardest hit by the pandemic, are strongly welcomed.

The monetary policy package

To sum up, a cross-check of the outcome of the economic analysis with the signals coming from the monetary analysis confirmed that an ample degree of monetary accommodation is necessary for the robust convergence of inflation to levels that are below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. Against this background, on 10 September 2020, the Governing Council reconfirmed the set of accommodative monetary policy measures in place.

- The Governing Council decided to keep the key ECB interest rates unchanged. These are expected to remain at their present or lower levels until the inflation outlook robustly converges to a level sufficiently close to, but below, 2% within the projection horizon, and such convergence has been consistently reflected in underlying inflation dynamics.

- The Governing Council decided to continue its purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) with a total envelope of €1,350 billion. These purchases contribute to easing the overall monetary policy stance, thereby helping to offset the downward impact of the pandemic on the projected path of inflation. The purchases will continue to be conducted in a flexible manner over time, across asset classes and among jurisdictions. This allows the Governing Council to effectively stave off risks to the smooth transmission of monetary policy. Net asset purchases will be conducted under the PEPP until at least the end of June 2021 and, in any case, until the Governing Council judges that the coronavirus crisis phase is over. In addition, reinvestments of the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the PEPP will be conducted until at least the end of 2022. In any case, the future roll-off of the PEPP portfolio will be managed to avoid interference with the appropriate monetary policy stance.

- Net purchases under the asset purchase programme (APP) will continue at a monthly pace of €20 billion, together with the purchases under the additional €120 billion temporary envelope until the end of the year. The Governing Council continues to expect monthly net asset purchases under the APP to run for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of the ECB’s policy rates, and to end shortly before the Governing Council starts raising the key ECB interest rates. In addition, the Governing Council intends to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.

- Finally, the Governing Council will also continue to provide ample liquidity through its refinancing operations. In particular, the latest operation in the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) has registered a very high take-up of funds, supporting bank lending to firms and households.

The monetary policy measures that the Governing Council has taken since early March are providing crucial support to underpin the recovery of the euro area economy and to safeguard medium-term price stability. In particular, they support liquidity and funding conditions in the economy, help to sustain the flow of credit to households and firms, and contribute to maintaining favourable financing conditions for all sectors and jurisdictions. At the same time, in the current environment of elevated uncertainty, the Governing Council will carefully assess incoming information, including developments in the exchange rate, with regard to its implications for the medium-term inflation outlook. The Governing Council continues to stand ready to adjust all of its instruments, as appropriate, to ensure that inflation moves towards its aim in a sustained manner, in line with its commitment to symmetry.

1 External environment

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic remains the major source of uncertainty for the global economy. Around mid-May the number of new cases stabilised temporarily, which led to a gradual lifting of containment measures. However, thereafter the numbers picked up again – especially in the United States, as well as in Brazil and other emerging market economies – until new infections globally started to plateau in early August. But the infection rate remains high and numbers of new cases are rising in Europe and some other regions, fuelling fears of a strong resurgence in coronavirus infections. These fears have been weighing negatively on consumer confidence. Incoming data confirm that global economic activity bottomed out in the second quarter and started to rebound in line with the gradual lifting of containment measures from mid-May onwards. The September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections envisage that world real GDP (excluding the euro area) will contract by 3.7% this year and expand by 6.2% and 3.8% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The contraction in global trade will be more severe than the fall in real GDP given both its more pronounced procyclicality, especially during economic downturns, and also the distinctive nature of the COVID-19 crisis, which has entailed disruptions in global production chains and increased trade costs because of the containment measures. Risks to the global outlook remain skewed to the downside given the persistent uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic, which may leave lasting scars on the global economy. Other downside risks relate to the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, the risk of a rise in trade protectionism, and, relatedly, longer-term negative effects on global supply chains.

Global economic activity and trade

The global economy entered a deep, synchronised recession in the first half of 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The outbreak and the containment measures adopted to limit the spread of the virus weighed on economic activity causing an unprecedented and synchronised fall in global output, which reached its trough in April 2020. Global uncertainty soared to levels not seen since the global financial crisis. Incoming national accounts data for the second quarter confirm a sharp contraction in economic activity. The fall in global trade was even sharper, although less pronounced than envisaged in the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections. This suggests a lower global trade elasticity than previously assumed. At the same time, China was able to start lifting containment measures around late March and see its economy return to positive growth rates already in the second quarter.

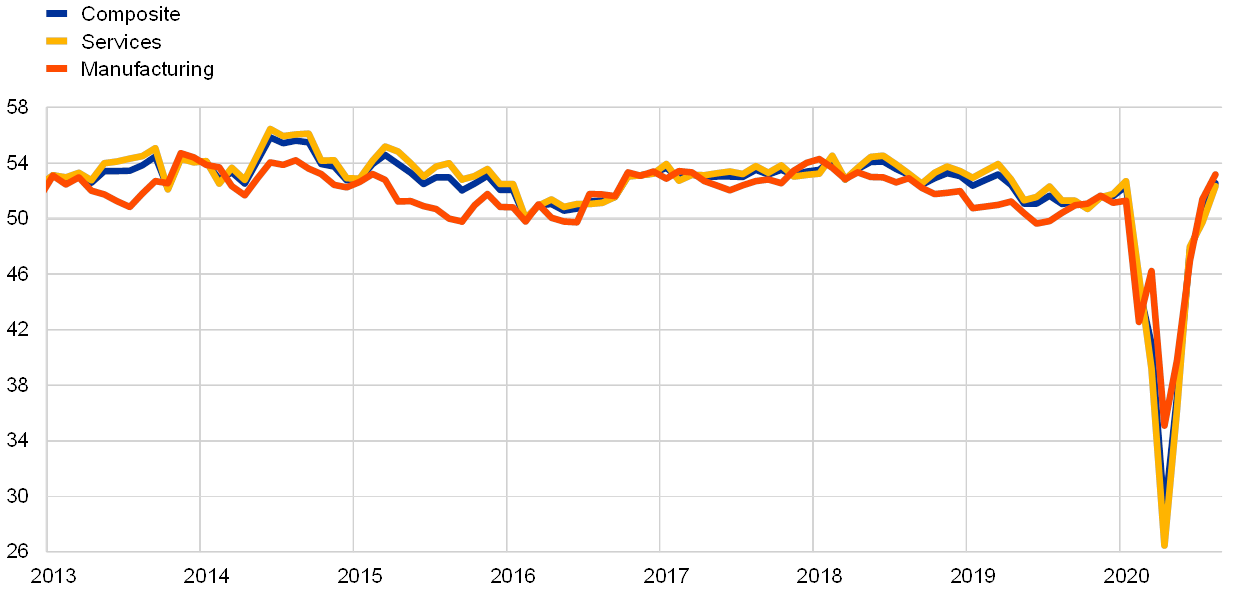

Once the spread of COVID-19 started to abate and containment measures started to be lifted, the global economy began to recover, as confirmed by survey data. With restrictions having been eased and production having started to normalise, global economic activity and trade are expected to rebound from the low levels of the second quarter. Global composite output Purchasing Managers Indices (PMIs; excluding the euro area) have been improving steadily since reaching the trough in April (see Chart 1). In August, the global composite output PMI (excluding the euro area) rose for a fourth consecutive month, up to 52.6 from 50 in July and from a low of 28.6 in April. The rebound is broad-based across both the manufacturing and service sectors. The recovery, however, appears uneven across countries. Among advanced economies, the composite output PMI continued growing in the United States and the United Kingdom, while it remained in contractionary territory in Japan. Among emerging economies, the composite output PMI increased further in China, Russia and Brazil but continued to show a contraction in India.

Chart 1

Global composite output PMI and sub-indices (excluding the euro area)

(diffusion indices)

Sources: Markit and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for August 2020.

Global financial conditions have eased significantly in recent months. During the summer, the recovery in financial markets that had started in late March continued, with seemingly undiminished momentum across major advanced market economies and some emerging ones. Equity markets rallied to new record levels in the United States and multi-year highs in China, and continued to quickly recover the bulk of their losses elsewhere. Other risky market segments, including corporate bonds, also benefited from the bullish market sentiment. With risk-free sovereign yields broadly unchanged at or close to historically low levels, indices of financial conditions reached an all-time high in advanced economies, and were not far off record levels in emerging market economies. The ongoing rally in risky assets was driven by a string of positive macroeconomic data surprises and a further rise in risk appetite, partly reflecting increasing optimism about the early delivery of a vaccine. However, financial markets remain in alert mode as the outlook hinges on the uncertain path of the pandemic. Volatility remains well above historical averages and market perceptions of risk remain skewed to the downside.

Global real GDP (excluding the euro area) will decline by 3.7% this year. According to the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, global real GDP growth (excluding the euro area) is assumed to edge into positive territory in the second half of 2020, as containment measures continue to be lifted gradually. However, the rebound is limited, as it is assumed that uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic weighs on firms’ and consumers’ sentiment, some forms of social distancing remain in place and an effective medical solution only becomes available by mid-2021. The projection baseline is therefore compatible with infections continuing in some countries, while it is assumed that renewed outbreaks are dealt with by means of targeted containment measures which are assumed to be less disruptive of economic activity than earlier lockdowns.

The lingering uncertainty about the evolution of the pandemic delivers an incomplete economic recovery by the end of the projection horizon. The COVID-19 crisis has been a triple shock for the global economy[2]. Unlike past crises, it hit private consumption particularly hard in the first half of 2020. Looking ahead, while the negative effects of containment measures will likely dissipate and global production will gradually recover, continued uncertainty about the health and economic outlook will continue to weigh on consumption, thus holding back a more vigorous recovery in economic activity. Compared to the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the trajectory for the level of economic activity is broadly unchanged, remaining below the pre-COVID-19 baseline projection throughout the forecast horizon. Therefore, world real GDP growth (excluding the euro area) is projected to grow at 6.2% in 2021 and 3.8% in 2022.

In the United States, economic activity is recovering in the third quarter on the back of income support measures. Real GDP contracted by 31.7% annualised (-9.1% quarter on quarter) in the second quarter, according to the second estimate. This contraction was slightly smaller than reported in the advance estimate (-9.5% quarter on quarter), reflecting upward revisions to private inventory investment and personal consumption expenditures. Recent data releases for the United States have been positive overall. After large increases in May and June, sales of retail goods and food services rose by a modest 1.2% in July, but still exceeded pre-pandemic levels. Total personal consumption expenditure, however, remains far below its pre-pandemic level, as spending on other services has fallen. Household spending had been supported by increased unemployment benefits and one-off direct income support. These payments largely expired in August, leading to a sizeable drop in income which could further undermine consumption. As lockdown measures were eased around May, workers started to return to their jobs, reversing more than half of the temporary lay-offs reported in April. However, the pace of employment creation slowed in July compared to May and June and the unemployment rate still remains at historically high levels. Annual headline consumer price index (CPI) inflation increased to 1.0% in July from 0.6% in June. Core inflation rose strongly to 1.6% in July from 1.2% in June, driven by rising prices for shelter and medical services. Various inflation expectations indicators have picked up recently, approaching their long-term averages again. Nonetheless, the outlook for inflation remains very subdued as the economy continues to operate below potential.

In China, the economy is recovering strongly but retail sales remain weak. China’s GDP increased in the second quarter by 11.5% quarter on quarter, returning to above its level at the end of 2019. Investment was the largest driver of growth, together with net exports, while consumption remained a drag on growth. Incoming data suggest that most of the Chinese economy has rebounded to pre-COVID-19 levels, but retail sales remain weak. While industrial production has recovered robustly (+4.9% year on year in July) retail sales continue to decline (-2.6% year on year in July) presumably due to subdued household employment expectations. Fiscal policy remains supportive of economic activity, as expanded unemployment insurance, higher investments and tax relief measures are aimed at stabilising employment and economic growth. Monetary policy is also supportive, though given the rebounding economy the authorities are mindful that further credit growth could pose risks to financial stability.

In Japan, economic activity is recovering in the third quarter but private consumption remains weak. Real GDP declined by 7.9% quarter on quarter in the second quarter, according to the second estimate, and is slightly revised downward compared to the first estimate (‑7.8% quarter on quarter). A nationwide state of emergency in April and May dampened activity, with double-digit contractions in private consumption of services and in exports accounting for the bulk of the decline in activity. The former reflects the impact of the domestic lockdown, while the latter reflects a slump in external demand. Recovery in foreign demand has contributed to a significant rebound in industrial production in July. But the pace of economic recovery remains subdued as indicated by the composite output PMI which, while increasing for the fourth consecutive month in August to 45.2, still remains in contractionary territory (i.e. below the 50 threshold). Private consumption of services remains weak. The consumption activity index published by the Bank of Japan indicates that consumption of durable and non-durable goods increased in June, pointing to pent-up demand playing an important role in the first full month after the lockdown, but it weakened again in July. Consumption of services, which accounts for 51% of household consumption, remained almost 20% below its first-quarter level in June. Although improved mobility trends for visits to restaurants, shopping centres and theme parks may suggest an ongoing recovery, consumption of services has remained broadly unchanged in July as compared with June. This, together with signals that the improvement in consumer sentiment stalled in August, points to a very gradual recovery in consumption, partly related to the resurgence of new COVID-19 infections during the months of July and August.

In the United Kingdom, after an unprecedented decline in the second quarter, the recovery in economic activity looks timid and incomplete. Real GDP declined by 20.4% quarter on quarter in the second quarter, reflecting a broad-based contraction in all expenditure components and especially domestic demand. A double-digit contraction in private consumption has been reflected in a sharp increase in the saving ratio. Business investment fell by almost a third in the second quarter in an environment of extreme uncertainty. While the composite output PMI points to a rebound in activity in the third quarter, the outlook seems rather uncertain as broader survey data suggest continued weakness in business confidence, together with growing fears of unemployment and concerns about future economic prospects. Government support for the widely used furlough scheme has been extended as of 1 August until October, but the amount of support is lower and a discontinuation of the scheme is planned thereafter. The CPI and core inflation each rose by 0.4 percentage points in July, to 1.0% and 1.4%, respectively. The increase in prices was broad-based across items and partly related to the additional costs for “COVID-proofing” as reported by the Office for National Statistics (i.e. widespread cost increases for firms across the private sector linked to social distancing).

In central and eastern European countries, economic activity is expected to gradually recover, reflecting the lifting of containment measures. Real GDP in these countries contracted substantially in the first half of 2020 because of the measures adopted to limit the spread of COVID-19. With these measures gradually being relaxed and production normalising, activity is expected to bounce back and gradually recover as of the third quarter, supported by robust fiscal and monetary measures. Looking ahead, activity is expected to remain below its pre-2019 levels until the end of 2021.

In large commodity-exporting countries the outlook for economic activity remains uncertain given the still high number of infections. In Russia, real GDP in the second quarter was hit by a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, the restrictions adopted to control domestic infections – which dampened private consumption and investment – and global oil market gyrations weakening the energy sector. Against this backdrop, fiscal and monetary policy support have been gradually increased. Economic activity is projected to start recovering in the third quarter, but the outlook remains subject to considerable uncertainty. Not only is the number of new COVID-19 cases still high, investment prospects are also subdued, given the oil production cuts maintained by OPEC+ as well as lower commodity prices. In Brazil, the contraction in real GDP in the second quarter (-9.7% quarter on quarter) was broad-based across all items, with the exception of exports of goods and services, which expanded by around 1.8% quarter on quarter. The COVID-19 crisis struck just as economic sentiment had started to brighten following a period of subdued growth. As Brazil is now one of the countries worst affected by the pandemic, the recovery in the second half of the year is likely to be shallow. Given limited fiscal space, the amount of fiscal support has been modest and this support is expected to cease in October. Monetary policy is also supportive and interest rates have reached the historical low of 2%.

In Turkey, economic activity was left relatively unscathed by the pandemic in the first quarter of 2020, though it contracted in the second quarter. Activity remained robust until late March when the COVID-19 outbreak arrived in the country. In the second quarter real GDP growth contracted by 11% quarter on quarter, mostly on account of the services sector and to a lesser extent industrial activity. Following the gradual easing of containment measures starting in mid-May, the economy started to partially recover, driven by the manufacturing sector. However, as the services sector remains subdued, especially due to the poor performance of the tourism sector, it will continue to be a drag on growth in the third quarter. In response to the crisis, the authorities have stepped up fiscal and monetary policy stimulus to stabilise the economy, but the weak external demand continues to weigh on the short-term outlook. Pressure on the Turkish lira has intensified recently, triggered by concerns about the decline in foreign exchange reserves and the national authorities’ ability to continue defending the currency.

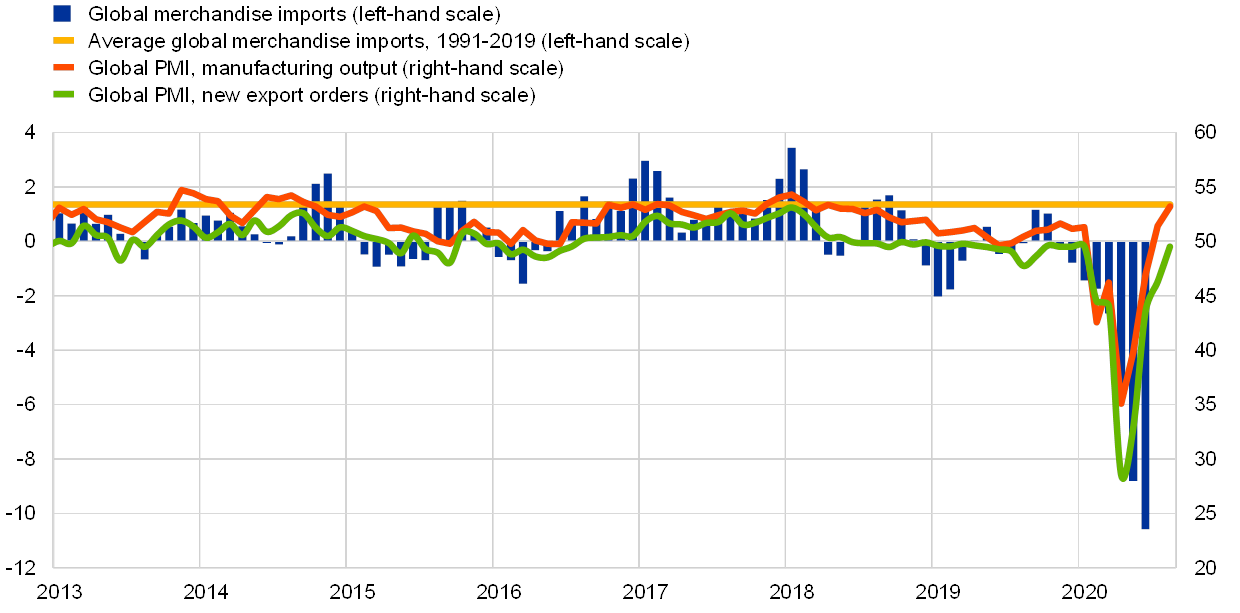

Global trade is expected to record a double-digit contraction in 2020. The sharp fall in global imports (excluding the euro area) in 2020 reflects both the strong procyclicality of trade, especially during economic downturns, and also the distinctive nature of the COVID-19 crisis. The fall in global demand, coupled with disruptions in global production chains and increased trade costs arising from the COVID-19-related containment measures have taken a toll on global trade. In the second quarter world merchandise imports (excluding the euro area) contracted by 10.5% quarter on quarter, though the downward momentum subsided somewhat in May, and a stronger rebound was recorded in June (+6.3% month on month). Survey data also point to a rebound in trade as the manufacturing PMI for new export orders rose in August for a fourth consecutive month, from 46.1 in June to 49.5 in August, and from a low of 27 in April (see Chart 2). Looking ahead, while global trade is expected to bounce back along with the gradual lifting of containment measures, some scarring effects may materialise. In the near term, as governments decide to keep selective travel restrictions in place, at least until a medical solution is found, this may further dampen trade by raising trade costs. Finally, as the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the dependence of several countries on external suppliers, this may result in new policies. Such policies might aim either to diversify global suppliers, so as to avoid mono-dependence, or to reshore production, thus negatively affecting complex global value chains. According to the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, global trade is projected to contract by 11.2% in 2020 and then expand by 6.8% and 4% in 2021 and 2022 respectively. Euro area foreign demand is projected to decline by 12.5% in 2020 and to grow by 6.9% in 2021 and 3.7% in 2022.

Chart 2

Surveys and global trade in goods (excluding the euro area) [replace]

(left-hand scale: three-month-on-three-month percentage changes; right-hand scale: diffusion indices)

Sources: Markit, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for August 2020 for the PMI data and June 2020 for global merchandise imports. The indices and data refer to the global aggregate excluding the euro area.

Uncertainty about the future evolution of the pandemic will continue to shape global economic prospects. Fears about a possible re-intensification of the pandemic, and the possible introduction of stricter containment measures, are weighing on firms’ investment and hiring decisions. This in turn is affecting consumer confidence and implies only a rather timid rebound in consumption. The more protracted such a situation is, the deeper the long-term scars the economy is likely to be left with. To illustrate the range of possible impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global economy, in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections the baseline is complemented by two alternative scenarios[3] – the mild and severe scenarios. These scenarios can be seen as providing an illustrative range around the baseline projection. The pandemic-related risks, in addition to other downside risks linked to the Brexit negotiations and a possible rise in trade protectionism, remain relevant. However, these other risks are themselves also probably conditional, to a degree, on the future course of the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy measures taken.

Global price developments

Oil prices have recovered amid the rebound in economic activity and falling oil supply due to production cuts agreed in early May. After having plunged below USD 20 per barrel in April, Brent crude oil prices had increased to around USD 45 per barrel as at the cut-off date for the September ECB staff macroeconomic projections. However, the simultaneous decline in the USD nominal effective exchange rate implies that, in many economies, the increase in oil prices was less pronounced in domestic currency terms. The partial recovery in oil prices appears to be driven by stronger than expected demand for oil because of the easing of lockdown measures, although overall, oil demand is still expected to remain subdued and below its 2019 levels throughout 2020 and 2021. On the supply side, in early May OPEC+ agreed on cutting production by almost ten thousand barrels per day, which, together with significant shut-ins of oil production in the United States and Canada, supported oil prices. The recovery in oil prices slowed down in August, after voluntary production cuts by Saudi Arabia expired and global oil demand stalled. Compared with the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the crude oil price assumptions in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections have been revised upward by 18.8%, 27.8% and 20.8% in 2020, 2021 and 2022, respectively. Since the cut-off date for the September staff projections, the price of crude oil has decreased, with Brent crude standing at around USD 40 per barrel on 9 September. Looking ahead, even though the oil price futures curve is only slightly upward sloping, crude oil prices are likely to remain volatile. This is a reflection of the fact that the economic outlook remains highly uncertain and storage capacity utilisation is exceptionally high.

Global inflation remains subdued even though the drag from energy prices has lessened recently. Annual consumer price inflation in the OECD has increased gradually from 0.7% in May to 1.2% in July (see Chart 3). The downward drag from annual energy price inflation has lessened in recent months. Energy prices declined by 8.4%, which was less than in June (-9.5%). At the same time, food price inflation decreased to 3.8% in July compared to June’s reading of 4.6%. Annual OECD CPI inflation, excluding food and energy, ticked up slightly to 1.7% in July. Across advanced economies, annual headline consumer price inflation increased in the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan while it decreased to 0.1% in Canada in July (compared with 0.7% in June). Annual headline inflation rose moderately in all major non-OECD emerging market economies in July.

Chart 3

OECD consumer price inflation

(year-on-year percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: OECD and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for July 2020.

Global inflation is expected to remain relatively weak amid low oil prices and weak demand. Weak demand, a sharp deterioration in labour markets and greater slack are likely to dampen underlying inflation pressures globally. Lower oil prices explain much of the downward revision to euro area competitors’ export prices (in national currency) in 2020. As the price of crude oil is expected to gradually increase over the projection horizon, this impact will dissipate and euro area competitors’ export prices are projected to return to their long-term averages towards the end of 2021.

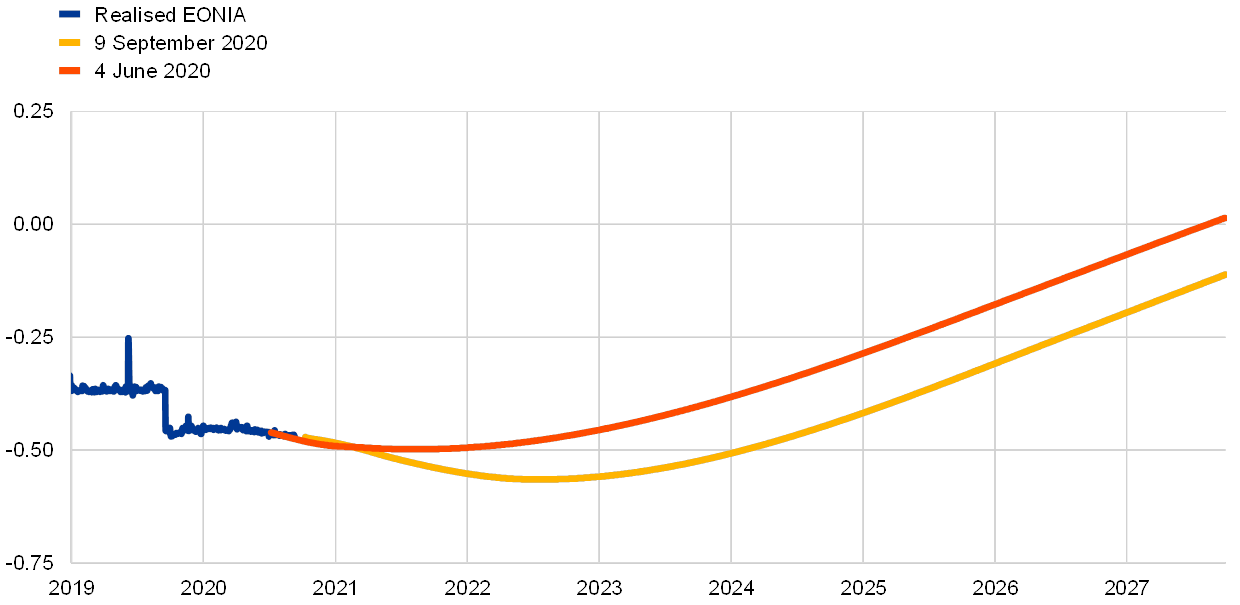

2 Financial developments

Over the review period (4 June 2020 to 9 September 2020) the forward curve of the euro overnight index average (EONIA) shifted downwards. Although mildly inverted at the short end, the curve does not signal firm expectations of a rate cut in the very near term. In a continuation of developments over the summer, long-term euro area sovereign bond spreads decreased over the review period amid a combination of monetary and fiscal support. Prices of risk assets increased somewhat, mainly against the backdrop of a generally more positive short-term earnings outlook. In foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated strongly in trade-weighted terms.

The EONIA and the new benchmark euro short‑term rate (€STR) averaged -46 and -55 basis points, respectively, over the review period.[4] Excess liquidity increased by €807 billion to around €2,982 billion. This change mainly reflects the take-up of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III), as well as the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), and the asset purchase programme (APP).[5]

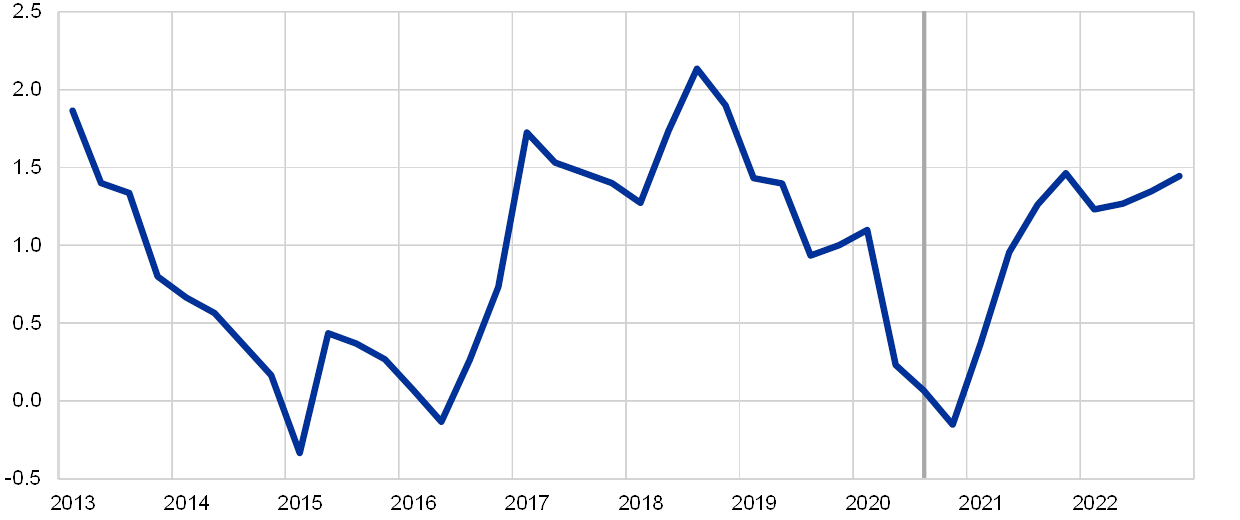

The EONIA forward curve shifted downwards over the review period, especially at medium and long-term horizons, and the curve has become mildly inverted (see Chart 4). Despite the inversion, the curve does not suggest firm market expectations of an imminent rate cut. Overall, EONIA forward rates remain below zero for horizons up to 2028, reflecting continued market expectations of a prolonged period of negative interest rates.

Chart 4

EONIA forward rates

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

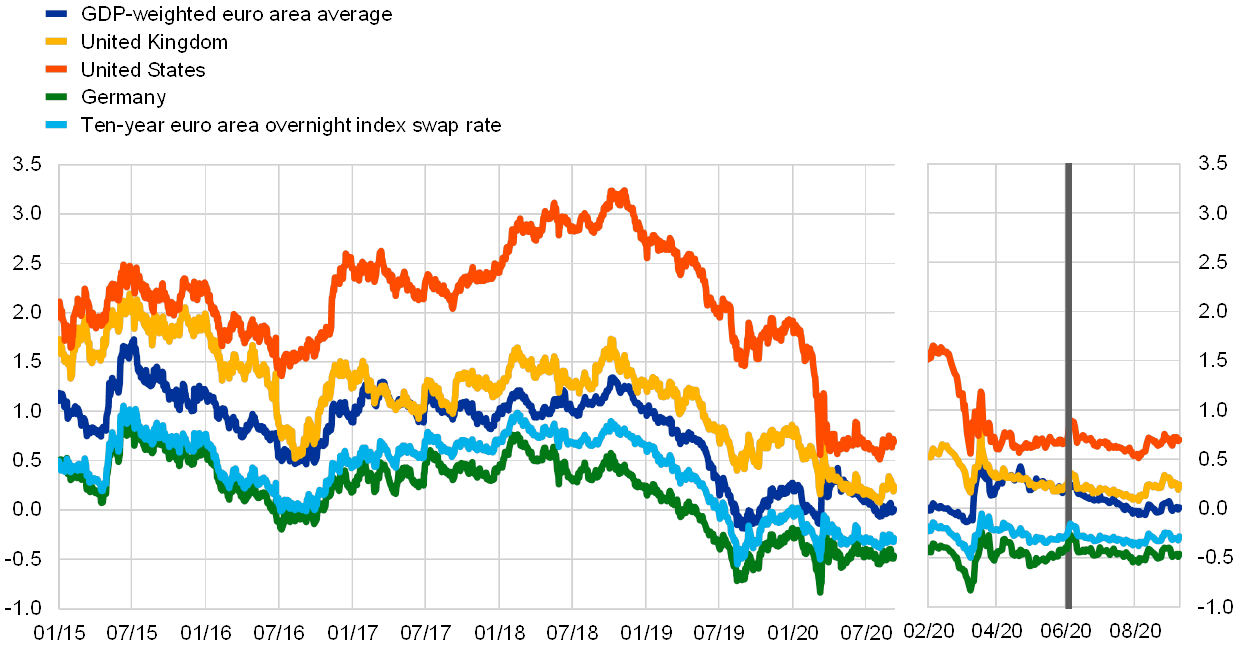

Long-term sovereign bond yields decreased across major jurisdictions in the period under review (see Chart 5). The GDP-weighted euro area ten-year sovereign bond yield declined by 23 basis points to 0.01%, owing to a combination of slightly lower risk-free rates and tightening sovereign spreads (see Chart 6). Ten-year sovereign bond yields in the United States and the United Kingdom decreased by 5 and 4 basis points respectively, bringing both close to historical lows.

Chart 5

Ten-year sovereign bond yields

(percentages per annum)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 4 June 2020. The latest observations are for 9 September 2020.

The spreads of euro area sovereign bonds relative to overnight index swap rates narrowed further amid monetary and fiscal support (see Chart 6). A combination of monetary and fiscal policy measures put in place to support the economy (including the Next Generation EU instrument) helped sovereign spreads to decline further throughout the review period. The ten-year German, French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese sovereign spreads decreased by 6, 12, 41, 22 and 17 basis points to reach -0.18, 0.12, 1.37, 0.63 and 0.65 percentage points respectively. Consequently, the GDP-weighted euro area ten-year sovereign spread decreased by 17 basis points to reach 0.29 percentage points, thereby standing only slightly above its level at the beginning of the year.

Chart 6

Ten-year euro area sovereign bond spreads vis-à-vis the overnight index swap rate

(percentage points)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The spread is calculated by subtracting the ten-year overnight index swap rate from the ten-year sovereign bond yield. The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 4 June 2020. The latest observations are for 9 September 2020.

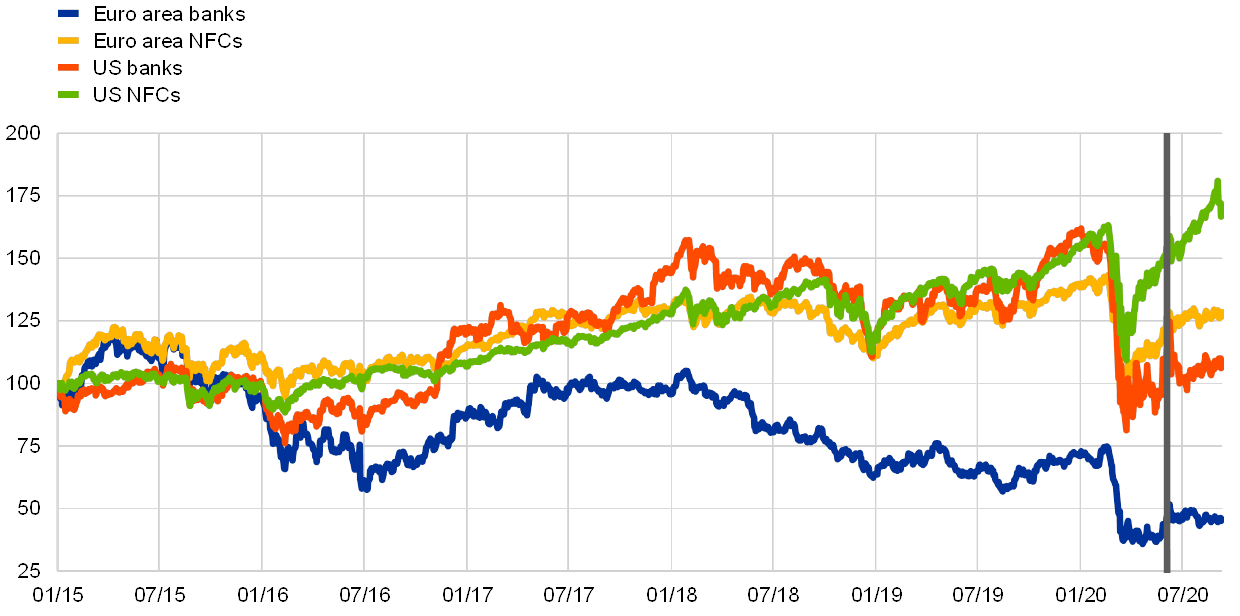

Equity price indices for euro area and US non-financial corporations (NFCs) increased as the short-term earnings outlook improved significantly (see Chart 7). With the increased optimism on the economic outlook, the earnings expectations of euro area firms have improved markedly from extremely low levels, and earnings are consequently expected to grow throughout the remainder of the year. This had a positive influence on the equity prices of euro area NFCs in the review period, which increased by around 2%. An even stronger increase of around 10% was visible in the United States, where NFC prices are close to record highs. By contrast, bank equity prices in the euro area and the United States decreased by 2% and 5% respectively, as the still uncertain outlook and potential for rising corporate defaults continued to weigh on the sector’s profit expectations.

Chart 7

Euro area and US equity price indices

(index: 1 January 2015 = 100)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

Notes: The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 4 June 2020. The latest observations are for 9 September 2020.

Euro area corporate bond spreads continued to narrow (see Chart 8). Spreads on investment-grade NFC bonds and financial sector bonds (relative to the risk-free rate) decreased by 38 and 37 basis points respectively. Overall, the decrease largely reflects a decline in the excess bond premium, i.e. the component of corporate bond spreads that is not explained by credit fundamentals (as measured by ratings and expected default frequencies), which have remained largely stable. Despite the significant compression since March, corporate bond spreads remain somewhat above levels prior to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, which may reflect market expectations of a rise in corporate defaults over the next few quarters.

Chart 8

Euro area corporate bond spreads

(basis points)

Sources: Markit iBoxx indices and ECB calculations.

Notes: Spreads are calculated as asset swap spreads to the risk-free rate. The indices comprise bonds of different maturities (but at least one year remaining) with an investment-grade rating. The vertical grey line denotes the start of the review period on 4 June 2020. The latest observations are for 9 September 2020.

In foreign exchange markets, the euro appreciated strongly in trade-weighted terms (see Chart 9). The nominal effective exchange rate of the euro, as measured against the currencies of 42 of the euro area’s most important trading partners, appreciated by 2.8% over the review period. Regarding bilateral exchange rate developments, the effective appreciation of the euro was very broad-based across the currencies of almost all major trading partners of the euro area. In particular, the euro appreciated strongly against the US dollar (by 4.6%) reflecting a broader weakening of the US dollar amid improving risk sentiment in the context of the ongoing global recovery. The euro also strengthened against the Japanese yen (by 2.1%), the pound Sterling (by 1.7%) and the Chinese renminbi (by 0.6%) and appreciated strongly against the currencies of most major emerging market economies, in particular the Russian rouble, the Turkish lira and the Brazilian real. Regarding the currencies of non-euro area EU Member States, the euro appreciated against the Hungarian forint, whereas it weakened against most others as these recovered some of the losses recorded during the intensification of the coronavirus pandemic in March and April this year.

Chart 9

Changes in the exchange rate of the euro vis-à-vis selected currencies

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Notes: EER-42 is the nominal effective exchange rate of the euro against the currencies of 42 of the euro area’s most important trading partners. A positive (negative) change corresponds to an appreciation (depreciation) of the euro. All changes have been calculated using the foreign exchange rates prevailing on 9 September 2020.

3 Economic activity

Euro area real GDP dropped by 11.8% quarter on quarter in the second quarter of 2020 due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic that hit the global economy. While this sharp contraction was essentially driven by the collapse in activity observed in March and April, incoming data since May have signalled that the economy is recovering. Both hard data and surveys are consistent with a significant rebound in GDP growth in the third quarter. Alongside the rebound in industrial and services production, there are signs of a recovery in consumption in line with expectations. Recently, momentum has slowed in the services sector compared with the manufacturing sector, which is also visible in survey results for August. The increases in coronavirus infection rates during the summer months constitute headwinds to the short-term outlook. Looking ahead, a further sustained recovery remains highly dependent on the evolution of the pandemic and the success of containment policies. While the uncertainty related to the evolution of the pandemic will likely dampen the strength of the recovery in the labour market and in consumption and investment, the euro area economy should be supported by favourable financing conditions, an expansionary fiscal stance and a strengthening in global activity and demand. This assessment is broadly reflected in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. These projections foresee annual real GDP declining by 8.0% in 2020, before increasing by 5.0% in 2021 and 3.2% in 2022. Compared with the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for real GDP growth has been revised up by 0.7 percentage points for 2020, and revised down by 0.2 and 0.1 percentage points for 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Economic activity in the euro area experienced an unprecedented fall in the second quarter of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the related containment measures. Real GDP fell by 11.8% quarter on quarter in the second quarter of 2020 against the backdrop of lockdown measures at their strictest in April before being eased gradually over the following months. Compared with the fourth quarter of 2019, real GDP thus decreased by 15.1% overall in the first half of 2020, bringing it back to levels last seen in the first quarter of 2005.

The contraction caused by the pandemic was spread broadly across countries and sectors. GDP declined in all euro area countries in the second quarter of 2020, with the size of the fall reflecting the impact of the pandemic and the timing and stringency of lockdown measures in each country. Among the larger euro area economies, GDP declined by 18.5% in Spain, 13.8% in France, 12.4% in Italy, 9.7% in Germany and 8.5% in the Netherlands quarter on quarter.

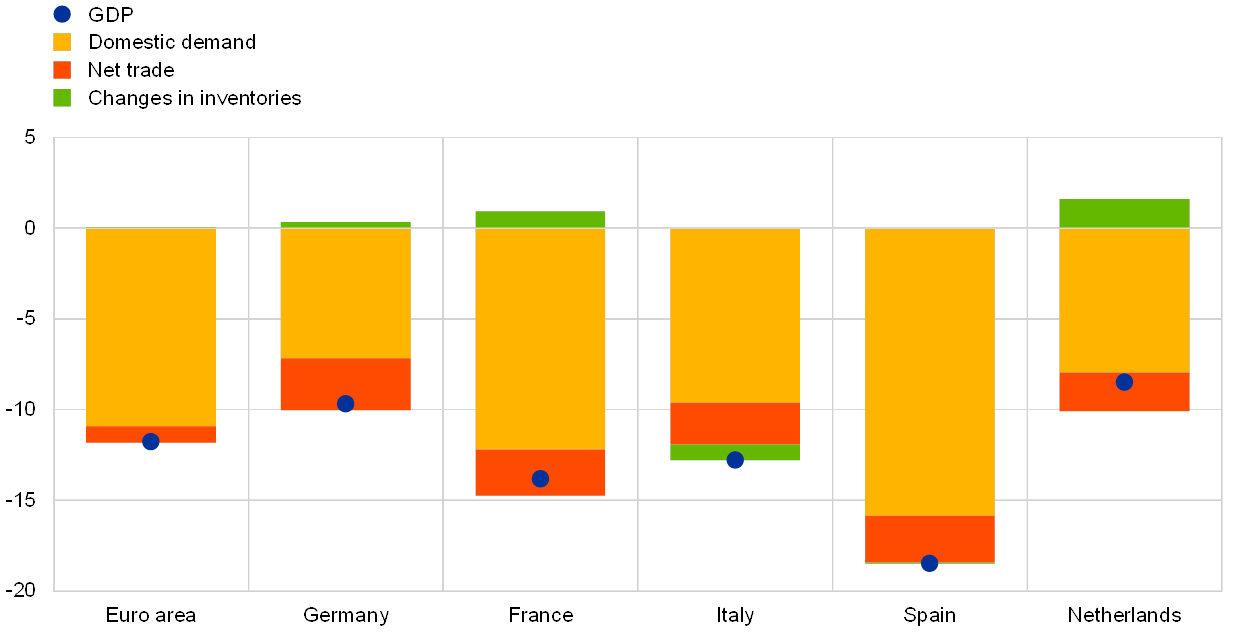

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented drop in domestic demand and services activity. As the expenditure-side breakdown of GDP (Chart 10) suggests, the fall in activity in the second quarter of 2020 was driven by a strong decline in domestic demand (-10.9%). Unlike during past recessions (such as the global financial crisis of 2007-08), it is activity in the services sector that has been hit hardest, due to the nature of social distancing measures. Net exports also contributed negatively to growth, albeit to a much lesser extent (-0.9%). Finally, the contribution from changes in inventories was marginally positive (+0.1%).

Chart 10

Changes in real GDP and contributions of expenditure components in the second quarter of 2020

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes)

Source: Eurostat.

Euro area labour markets have been severely affected by COVID-19 containment measures. Employment decreased by 2.9% in the second quarter of 2020, following a decline of 0.3% in the first quarter. This implies that, in the second quarter of 2020, there were 5.1 million fewer people employed than in the last quarter of 2019. Policy support measures, such as job retention schemes and similar arrangements aimed at preventing redundancies and supporting self-employed workers, mostly explain the smaller decline in employment compared with economic activity. These schemes preserve employment relationships and limit dismissals while helping firms to reduce their payroll costs during a cyclical downturn, so that the workers are available and the firms ready to resume activity once lockdown measures are lifted.[6] As such, short-time work schemes limit increases in unemployment while allowing the labour market to deal flexibly with cyclical fluctuations, for instance through a substantial reduction in hours worked per person employed for a predetermined length of time. Average hours worked declined by 10.2% in the second quarter of 2020, following a quarterly decrease of 3.8% in the first quarter. This implies that the fall in average hours worked accounts for more than 75% of the adjustment in total hours worked. The rest is attributable to employment. The decline in employment recorded during the second quarter is therefore smaller than the decline in GDP, implying a marked 12.1% decline in labour productivity per person employed in that period. By contrast, total hours worked declined by more than GDP, with labour productivity per hour worked increasing by 1.2% in the second quarter of 2020 on a quarterly basis.

Labour market indicators point towards continued job losses in the third quarter. The euro area unemployment rate increased to 7.9% in July 2020 from 7.7% in June. Between February and July 2020, the unemployment rate increased by 0.7 percentage points, which is less than the 1.3 percentage point increase observed between September 2008 and February 2009 following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. This increase does not fully capture the impact of the pandemic, as it is eased by the labour market policies adopted to bolster employment and prevent permanent lay-offs. It is also linked to transitions from employment and unemployment into inactivity due to the economic effects of lockdowns and the continued difficulties faced by workers looking for jobs as the containment measures were gradually phased out. Recent survey-based indicators continue to point towards job losses in the third quarter, despite the effect of the labour market policies currently in place (Chart 11).

Chart 11

Euro area employment, PMI assessment of employment and unemployment

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes; diffusion index; percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat, Markit and ECB calculations.

Notes: The Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) is expressed as a deviation from 50 divided by 10. The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2020 for employment, August 2020 for the PMI and July 2020 for the unemployment rate.

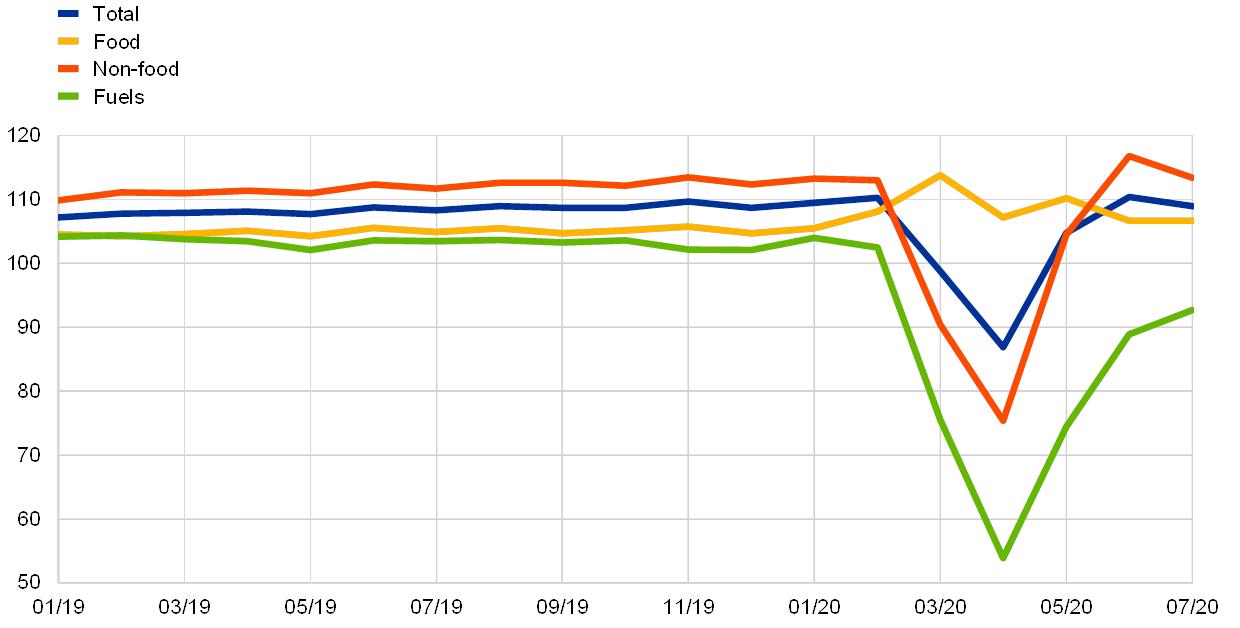

Consumer spending increased significantly in June and July, but its recovery remains far from complete. Consumer confidence edged up in August (to -14.7), but remained well below its pre-pandemic level (-8.8 in the first quarter of 2020). The volume of retail sales experienced a month-on-month decline of 1.3% in July (see Chart 12). Due to the exceptionally strong monthly increases in May and June of 20.6% and 5.3% respectively, however, sales in July stood 8.2% above the average reading in the second quarter and close to pre-pandemic levels. Sales of food products rose at the beginning of the outbreak (reflecting their nature as essential items, the substitution of restaurant spending and hoarding), while sales of automotive fuels plummeted before recovering. At the same time, sales of non-food products contracted sharply at first, now standing again at pre-pandemic levels in July. Despite the sharp rebound in retail trade, the remaining weakness in consumer spending is largely reflected in consumer services, notably in accommodation, entertainment and transport services.

Chart 12

Euro area retail trade

(index: 2005 = 100)

Source: Eurostat.

Looking forward, there is little sign of buoyancy in the demand for consumer goods. This can be seen in the assessment of the order books of consumer goods producers, the business expectations of retail firms and consumer intentions to make major purchases. While the drop in household incomes has been limited, the saving rate is expected to have risen sharply in the second quarter before declining again thereafter. This reflects forced or involuntary saving due to the constraints imposed by lockdown measures, while there is also evidence that standard channels, such as (countercyclical) precautionary savings, are also playing a significant role.[7]

Business investment rebounded to some extent as the economy reopened, but low demand and financial risks continue to weigh on the outlook for the coming quarters. Severe supply-side disruptions related to the COVID-19 outbreak caused the production of capital goods in the euro area to shrink by 21.3% quarter on quarter in the second quarter of 2020. At the same time, non-construction investment dropped by 20.9% quarter on quarter. These quarterly contractions do, however, mask a partial recovery in business investment from May onwards. In the course of May and June, the production of capital goods rose by 29.9%, albeit to a level that is still significantly below that seen in February this year. Survey indicators confirm the picture of a partial rebound, as highlighted by a recent improvement in the production expectations of capital goods producers for the months ahead and the assessment of their order books. In addition, the latest euro area bank lending survey[8] shows that the strong demand for loans and credit lines from euro area firms seen in the second quarter is expected to abate in the third quarter, indicating an improvement in business expectations. Nevertheless, still weak demand and the possibility of banks tightening credit standards for enterprises amid higher credit risk are expected to limit the rebound in investment demand in the coming quarters.

Housing investment plummeted by almost 14% over the first half of the year, while a gradual and partial recovery is likely to have started in the last months of the second quarter and continued thereafter. In the third quarter, short-term indicators are consistent with a strong – yet incomplete – rebound in construction activity. Despite the marked improvement in the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) for construction output in July and the European Commission’s confidence index for construction companies in August from their troughs in April, both indices still stood at historically low levels. This weakness may be related to binding constraints on construction production due to fewer building permits being issued and more stringent containment measures being imposed following the resurgence of COVID-19 cases in the summer months. At the same time, some stronger signs of recovery came from the PMI for construction business expectations and firms’ assessment of order books. These dynamics were associated with relatively unscathed demand for housing, as shown by the European Commission’s indicators of households’ intentions to build and renovate and the ECB’s bank lending survey, which shows resilient demand for housing loans in several countries, thanks in part to debt relief measures for household loans.

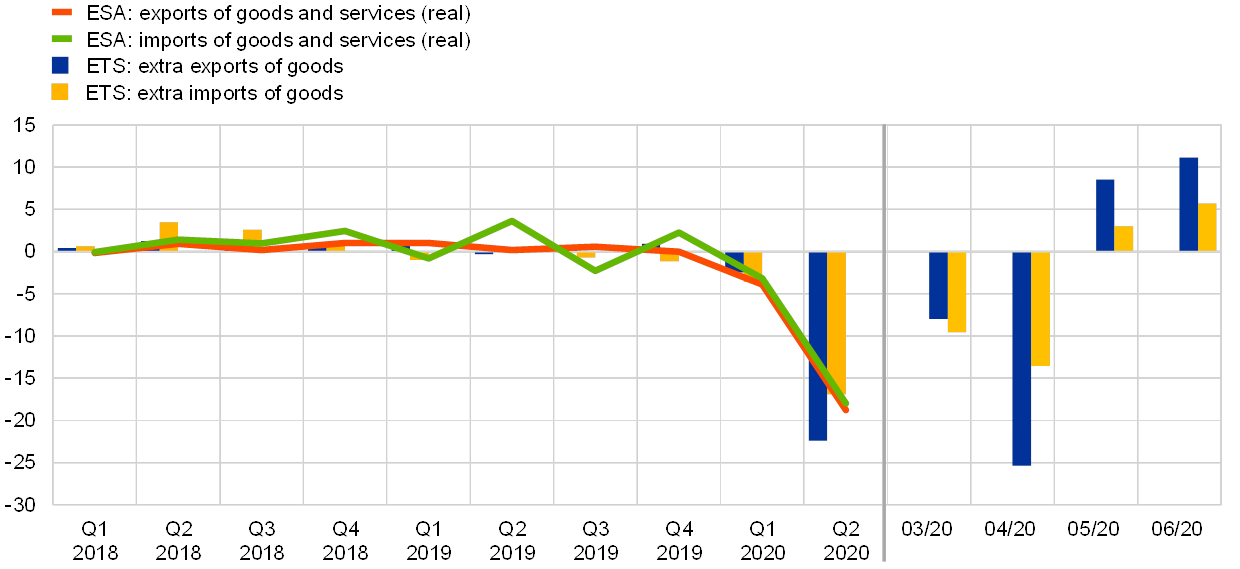

After the April trough, euro area trade rebounded at the end of the second quarter of 2020, albeit to a substantially lower level than before. Following on from a strong contraction in the first quarter, total euro area exports and imports fell by 18.8% and 18% respectively in the second quarter (Chart 13). Monthly data covering nominal trade in goods in May and June show that euro area exports and imports recovered about half of the losses suffered since the start of the pandemic, in a context where some containment measures were being eased. Intra euro area trade, which had contracted more than external trade in previous months, rebounded to a larger extent as the easing of pandemic-related restrictions was relatively more pronounced in Europe. The collapse in trade in services was even more pronounced, at 21.1% for exports and 25.4% for imports. Tourism, in particular, has been hit hard by travel bans and other lockdown measures, as evidenced by the sharp drop in airline capacity. Looking forward, the outlook for euro area exports is expected to improve to some extent. The PMI on euro area manufacturing new export orders confirms expansion in August (52). The European Commission’s assessment of export order book levels and the ECB’s industrial new orders indicators have improved for two consecutive months. As regards shipping indicators, those for maritime trade point to a gradual recovery, whereas those for air transport remain well below their levels of last year. All in all, the data point to a rebound in the coming months which, however, is not complete. On the services side, the PMI on euro area services new export orders still signals contraction and airline capacity indices flag a partial rebound for travel in the third quarter of 2020, especially to tourist destinations.

Chart 13

Euro area trade based on national accounts data (ESA) and external trade statistics (ETS)

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, month-on-month percentage changes for March, April, May, and June 2020)

Source: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: National accounts (ESA) data and external trade statistics (ETS) data are seasonally and working day adjusted. Differences in seasonal adjustment and other methodological differences can result in discrepancies between ESA and ETS data.

In the near term, a strong rebound in euro area growth is expected in the third quarter of 2020. The sharp contraction in the second quarter reflects the strong declines in activity seen in March and April. However, incoming data signal that the economy has been on a recovery path from May onwards. The improvement in surveys since May coincides with the easing of lockdown measures. The July and August readings of the composite output PMI and the European Commission’s Economic Sentiment Indicator (ESI) both stand well above the average levels in the second quarter. The PMI averaged 53.4 in July-August after 31.3 in the second quarter, while the ESI averaged 85.0 and 69.4 respectively over the same time periods. While activity in the manufacturing sector has continued to improve, momentum in the services sector has slowed somewhat recently.

Looking ahead, the rebound in euro area economic activity is expected to continue in the remainder of 2020, provided there is no major resurgence of the pandemic. Euro area activity is projected to rebound by 8.4% in the third quarter. Thereafter, the baseline projection rests on the key assumption of a partial success in containing the virus, with some resurgence in infections over the coming quarters leading to continued containment measures, albeit less strict than in the initial wave, until a medical solution becomes available by mid-2021. These containment measures, together with elevated uncertainty and worsened labour market conditions, are expected to continue to weigh on supply and demand. Nevertheless, substantial support from monetary, fiscal and labour market policies, all of which have been strengthened since the June 2020 Eurosystem staff projections, should maintain incomes and limit the economic scars which may follow the resolution of the health crisis. Such policies are also assumed to be successful in averting large financial amplification channels. Under these assumptions, real GDP in the euro area is projected to fall by 8.0% in 2020 and to rebound by 5.0% in 2021 and by 3.2% in 2022. By the end of the projection horizon, real GDP would stand 3½% below the level foreseen in the December 2019 Eurosystem staff projections, the last pre-pandemic projection exercise. The level of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2019 will be reached by the second half of 2022 (Chart 14). Against the background of the uncertainty around the trajectory of the pandemic, two alternative scenarios have been prepared. The mild scenario sees the pandemic shock as temporary, with the swift implementation of a medical solution allowing a further loosening of the containment measures. In this scenario, real GDP would decline by 7.2% this year, then rebound strongly in 2021. By the end of the horizon, real GDP would slightly exceed the level expected in the December 2019 Eurosystem staff projections. In contrast, the severe scenario with a strong resurgence of the pandemic implies a return to stringent containment measures, with substantial and permanent losses to activity. In this scenario, real GDP falls by 10% in 2020. By the end of the horizon, it stands around 9% below the level envisaged in the December 2019 Eurosystem staff projections.

Chart 14

Euro area real GDP (including projections)

(chain-linked volumes, million euro)

Sources: Eurostat and the article entitled “ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, September 2020”, published on the ECB’s website on 10 September 2020.

4 Prices and costs

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, euro area annual HICP inflation decreased to -0.2% in August, from 0.4% in July. On the basis of current and futures prices for oil and taking into account the temporary reduction in German VAT rates, headline inflation is likely to remain negative over the coming months before turning positive again in early 2021. Moreover, in the near term, price pressures will remain subdued owing to weak demand, lower wage pressures and the appreciation of the euro exchange rate, despite some upward price pressures related to supply constraints. Over the medium term, a recovery in demand, supported by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, will put upward pressure on inflation. This assessment is broadly reflected in the September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, which see annual HICP inflation at 0.3% in 2020, 1.0% in 2021 and 1.3% in 2022. Compared with the June 2020 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, the outlook for inflation is unchanged for 2020, has been revised up for 2021 and is unchanged for 2022. The unchanged projection for inflation in 2022 masks an upward revision to inflation excluding energy and food – in part reflecting the positive impact of the monetary and fiscal policy measures – which was largely offset by the revised path of energy prices. Annual HICP inflation excluding energy and food is expected to be 0.8% in 2020, 0.9% in 2021 and 1.1% in 2022.

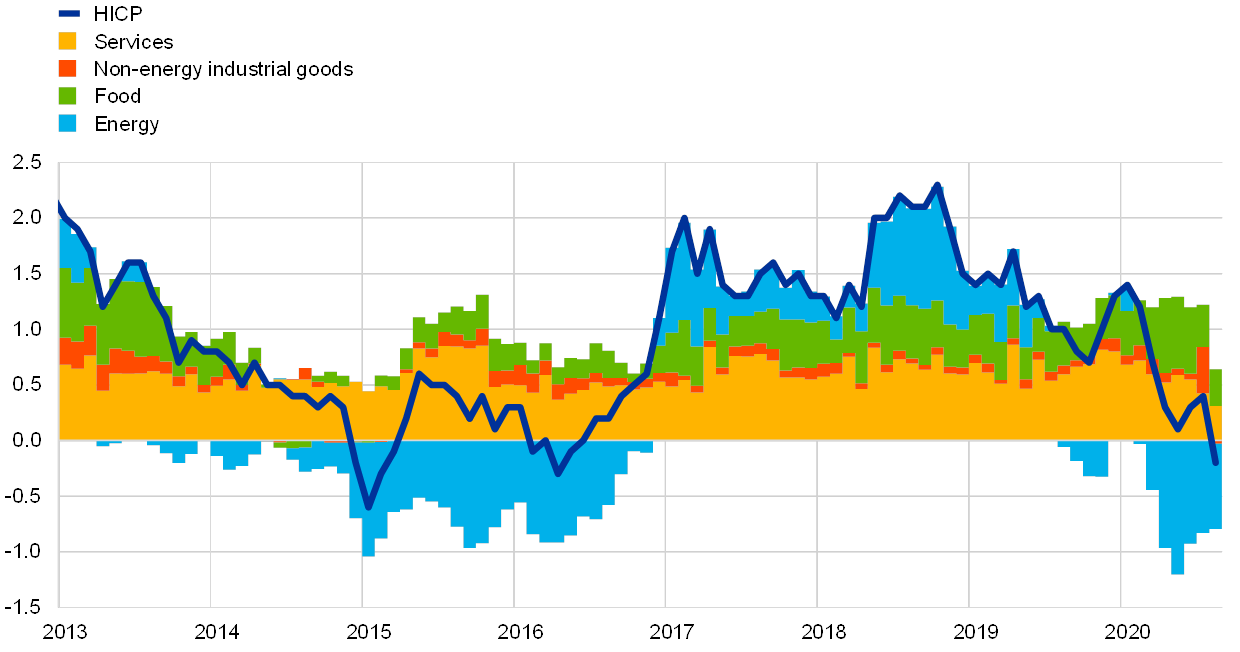

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, HICP inflation fell into negative territory in August. The decrease, from 0.4% in July to -0.2% in August, reflected a drop in HICP inflation excluding energy and food (HICPX) and lower food inflation, which were partially offset by less negative energy inflation (see Chart 15). Energy price inflation continued to rise, although the annual rate remains firmly negative reflecting the sharp drop in oil prices after the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Also pointing to some normalisation, food inflation returned to pre-pandemic levels in July and August, declining to 2.0% and further to 1.7% over the two consecutive months. According to Eurostat, HICP price collection difficulties due to the COVID-19 pandemic have continued to ease, with imputation rates now essentially back to normal levels.

Chart 15

Contributions of components of euro area headline HICP inflation

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for August 2020 (flash estimates). Growth rates for 2015 are distorted upwards owing to a methodological change (see the box entitled “A new method for the package holiday price index in Germany and its impact on HICP inflation rates”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2019).

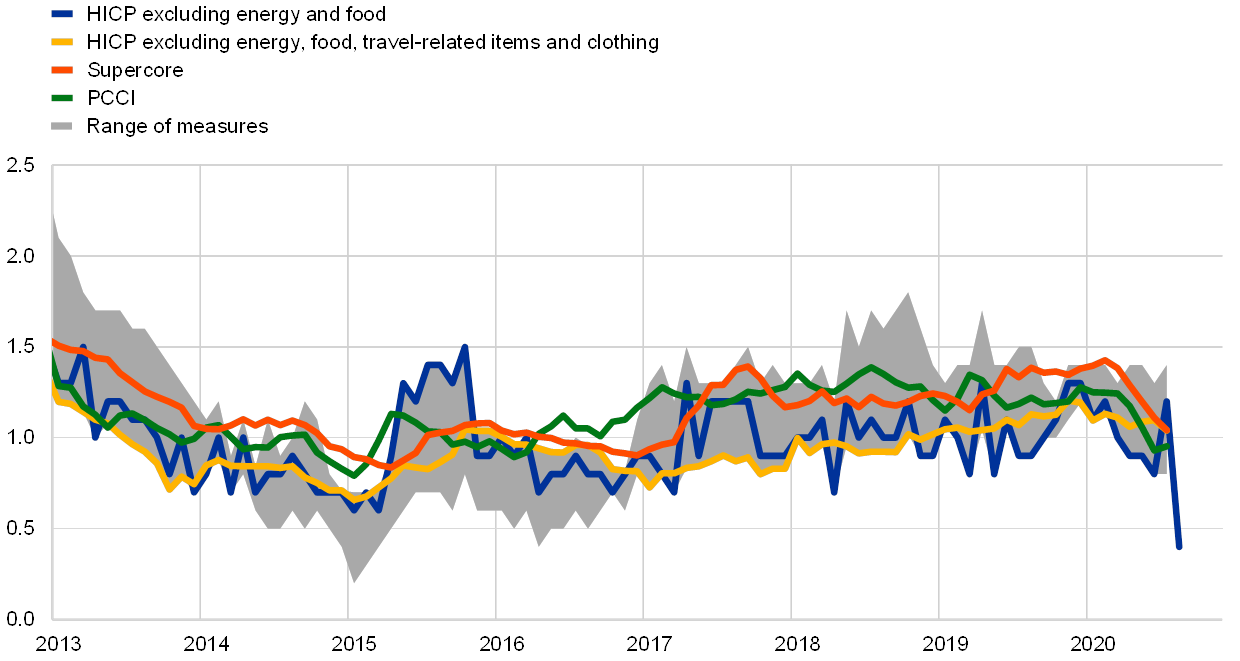

Despite a strong decline in HICPX inflation recently, overall, measures of underlying inflation point to a moderate weakening since the onset of the pandemic. HICPX inflation decreased to 0.4% in August, from 1.2% in July, due to declines in both non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation and services inflation. The sharp movements in HICPX inflation during July and August are mainly explained by temporary factors. NEIG inflation was -0.1% in August, after 1.6% in July and 0.2% over previous months. The recent volatility in NEIG inflation reflects, to a large degree, the impact of a postponement in seasonal sales of clothing and footwear in some euro area countries. This exerted strong upward pressure in July, which unwound in August. The latest movements in HICPX inflation also reflect the temporary reduction in German VAT rates since July 2020. Other measures of underlying inflation have shown a more moderate weakening (data are mainly available up to July; see Chart 16). HICP inflation excluding energy, food, travel-related items and clothing, the Persistent and Common Component of Inflation (PCCI) indicator, excluding energy, and the Supercore indicator[9] were all slightly down.

Chart 16

Measures of underlying inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for August 2020 for the HICP excluding energy and food (flash estimate) and for July 2020 for all other measures. The range of measures of underlying inflation consists of the following: HICP excluding energy; HICP excluding energy and unprocessed food; HICP excluding energy and food; HICP excluding energy, food, travel-related items and clothing; the 10% trimmed mean of the HICP; the 30% trimmed mean of the HICP; and the weighted median of the HICP. Growth rates for the HICP excluding energy and food for 2015 are distorted upwards owing to a methodological change (see the box entitled “A new method for the package holiday price index in Germany and its impact on HICP inflation rates”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2019).

Pipeline price pressures for the HICP non-energy industrial goods component have been strengthening moderately. Producer price inflation for domestic sales of non-food consumer goods, which is an indicator of price pressures at the later stages of the supply chain, edged up to 0.7% in July (an increase of 0.1 percentage points), slightly above its long-term average of 0.6%. The corresponding annual rate of import price inflation decreased slightly, however, to -0.7% in July, down by 0.2 percentage points from its June level, which may in part reflect some downward pressure from the recent appreciation of the euro effective exchange rate. Earlier in the domestic pricing chain, intermediate goods price inflation increased marginally despite the stronger euro. For intermediate goods, producer price inflation increased to -2.0% in July, from -2.5% in June, while import price inflation was broadly unchanged at -2.7%.

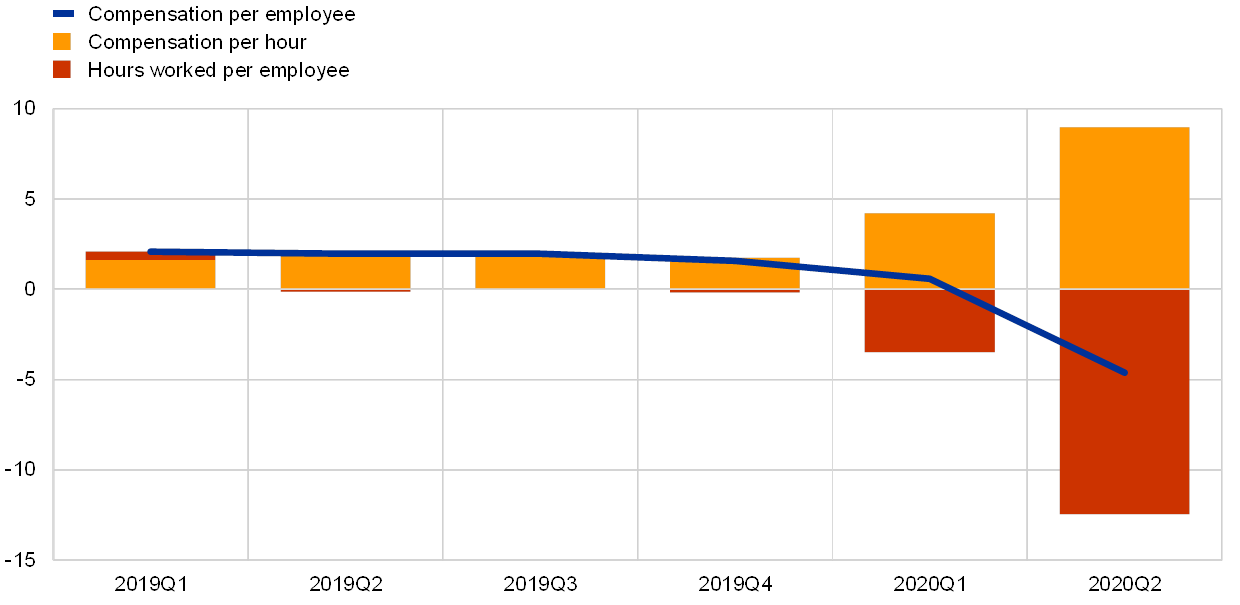

Growth in compensation per employee continued to show a pronounced decline in the second quarter of 2020, largely reflecting the fall in hours worked. Annual growth in compensation per employee fell to -4.6% during the second quarter, from 0.6% in the first quarter (see Chart 17). The decline was broad-based across sectors (with the exception of agriculture and fishing) and countries. The continued deceleration in euro area compensation per employee essentially reflects the significant reduction in hours worked per employee after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the related lockdown and containment measures. Annual growth in compensation per hour rose to 9.0% in the second quarter, from 4.2% in the previous quarter, owing to the significant reduction in actual hours worked per employee. These contrary developments reflect the impact of short-time work and temporary lay-off schemes in buffering labour income. Negotiated wages grew by 1.7% in the second quarter of the year, with the latest developments in compensation per employee implying a strong downward impact in the wage drift. Nevertheless, the deceleration in compensation per employee has exaggerated the loss in labour income, as a number of countries record government support, for statistical purposes, under transfers rather than compensation.

Chart 17

Decomposition of compensation per employee into compensation per hour and hours worked

(annual percentage changes; percentage point contributions)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2020.

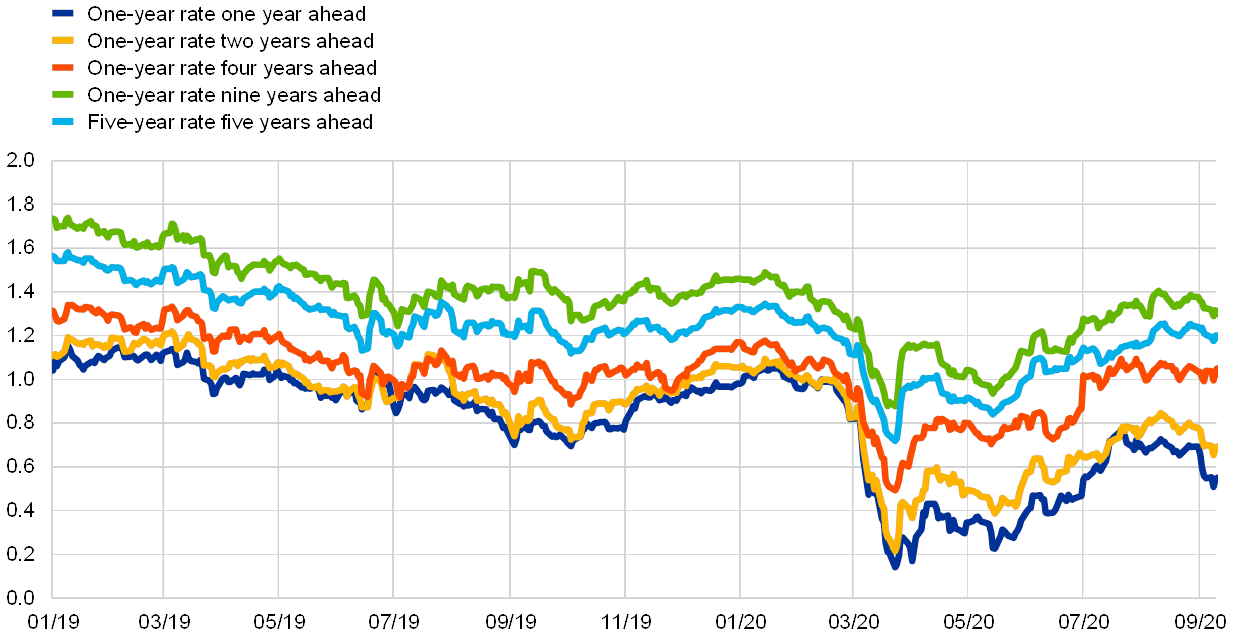

After falling to historical lows around mid-March, market-based indicators of longer-term inflation expectations have continued to recover, returning to their pre-pandemic levels albeit at still low levels (see Chart 18). This development reflects improvements in the global macroeconomic outlook and risk sentiment, as well as sizeable monetary and fiscal support. In a continuation of this trend, the five-year forward inflation-linked swap rate five years ahead rose further by around 10 basis points to stand at 1.20% on 4 September 2020, i.e. almost 50 basis points above its historical (mid-March) low of 0.72%. At the same time, the forward profile of market-based indicators of inflation expectations continues to indicate a prolonged period of low inflation. Inflation options markets also still signal considerable downside risks in the near term, as underlying deflation probabilities remain around historically elevated levels. According to the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters for the third quarter of 2020, conducted in the first week of July 2020, as well as the latest releases from Consensus Economics and the Euro Zone Barometer, survey-based longer-term inflation expectations remained at or close to historically low levels in July, reflecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, mitigation measures and continuing uncertainties.

Chart 18

Market-based indicators of inflation expectations

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Thomson Reuters and ECB calculations.

Note: The latest observations are for 9 September 2020.

The September 2020 ECB staff macroeconomic projections foresee an increase in headline inflation over the projection horizon. The baseline projections point to headline HICP inflation averaging 0.3% in 2020, 1.0% in 2021 and 1.3% in 2022 (see Chart 19). Compared with the June 2020 Eurosystem staff projections, the projection for HICP inflation is unchanged for 2020, revised up by 0.2 percentage points for 2021 and remains unchanged for 2022.In the short term, the previous collapse in oil prices, the appreciation of the euro and a temporary reduction in the VAT rates in Germany imply that euro area headline HICP inflation is likely to remain negative over the coming months. In 2021, base effects in the energy component and, to a lesser extent, the expected reversal of the VAT rate cut in Germany subsequently cause a mechanical rebound.[10] HICP inflation excluding energy and food is projected to decline until the end of 2020. Disinflationary effects are expected to be broad-based across the services and goods sectors, as demand remains weak. However, continued upward cost pressures related to supply-side limitations are expected to partly offset these effects. Over the medium term, inflation is projected to increase: oil prices are assumed to pick up and demand should recover, despite diminishing upward pressures from adverse supply effects linked to the pandemic and despite the appreciation of the euro. HICP inflation excluding energy and food is expected to be 0.8% in 2020 and 0.9% in 2021, before increasing to 1.1% in 2022.

Chart 19

Euro area HICP inflation (including projections)

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and the article entitled “ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, September 2020”, published on the ECB’s website on 10 September 2020.

Notes: The vertical line indicates the start of the projection horizon. The latest observations are for the second quarter of 2020 (data) and the fourth quarter of 2022 (projection). The cut-off date for data included in the ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area, September 2020, was 27 August 2020.

5 Money and credit

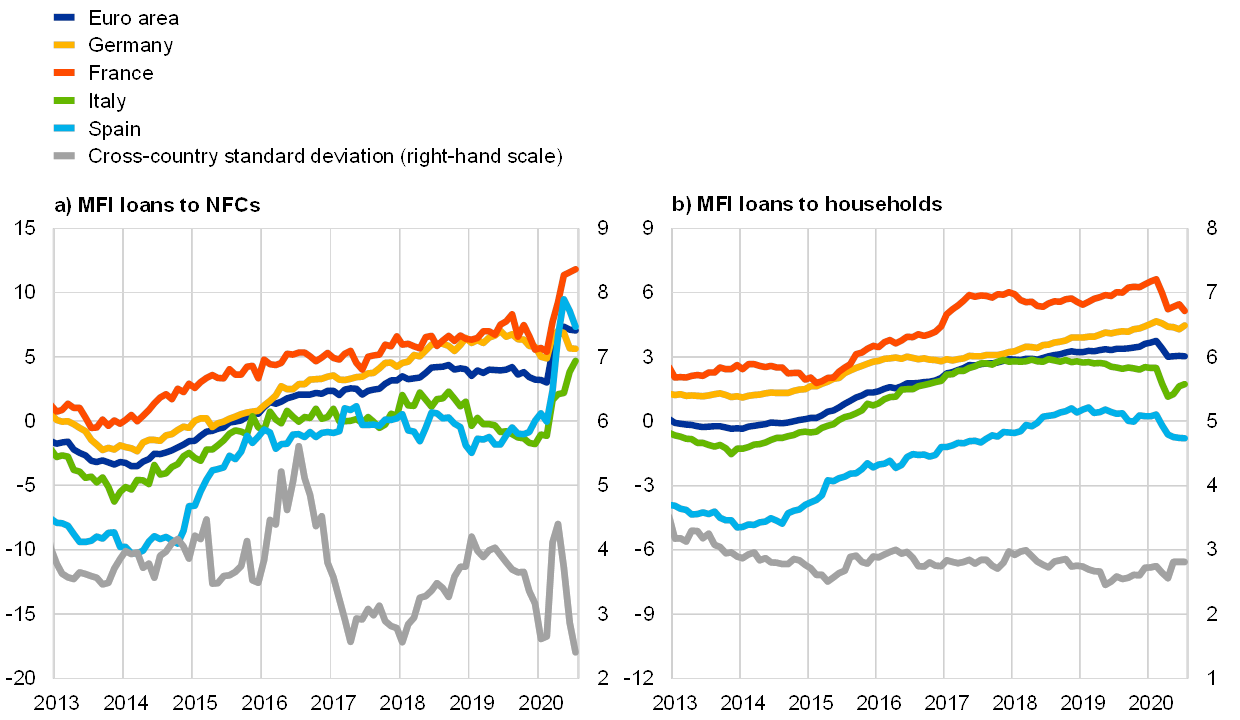

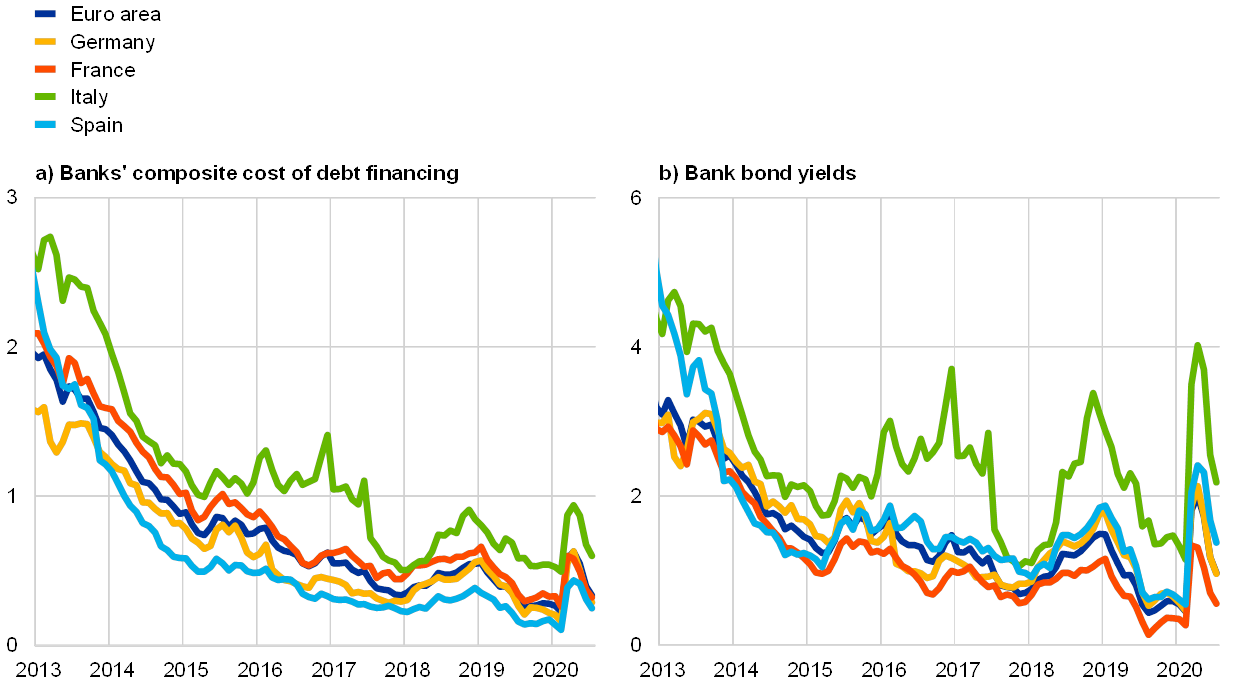

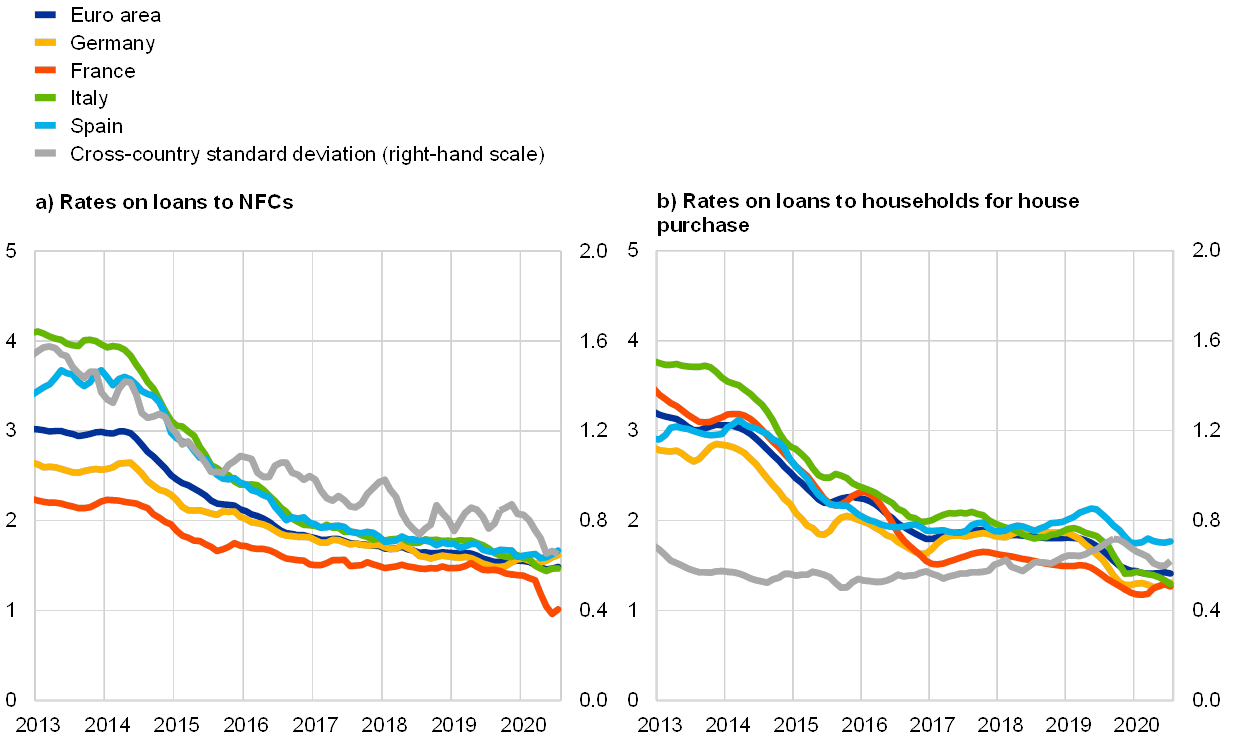

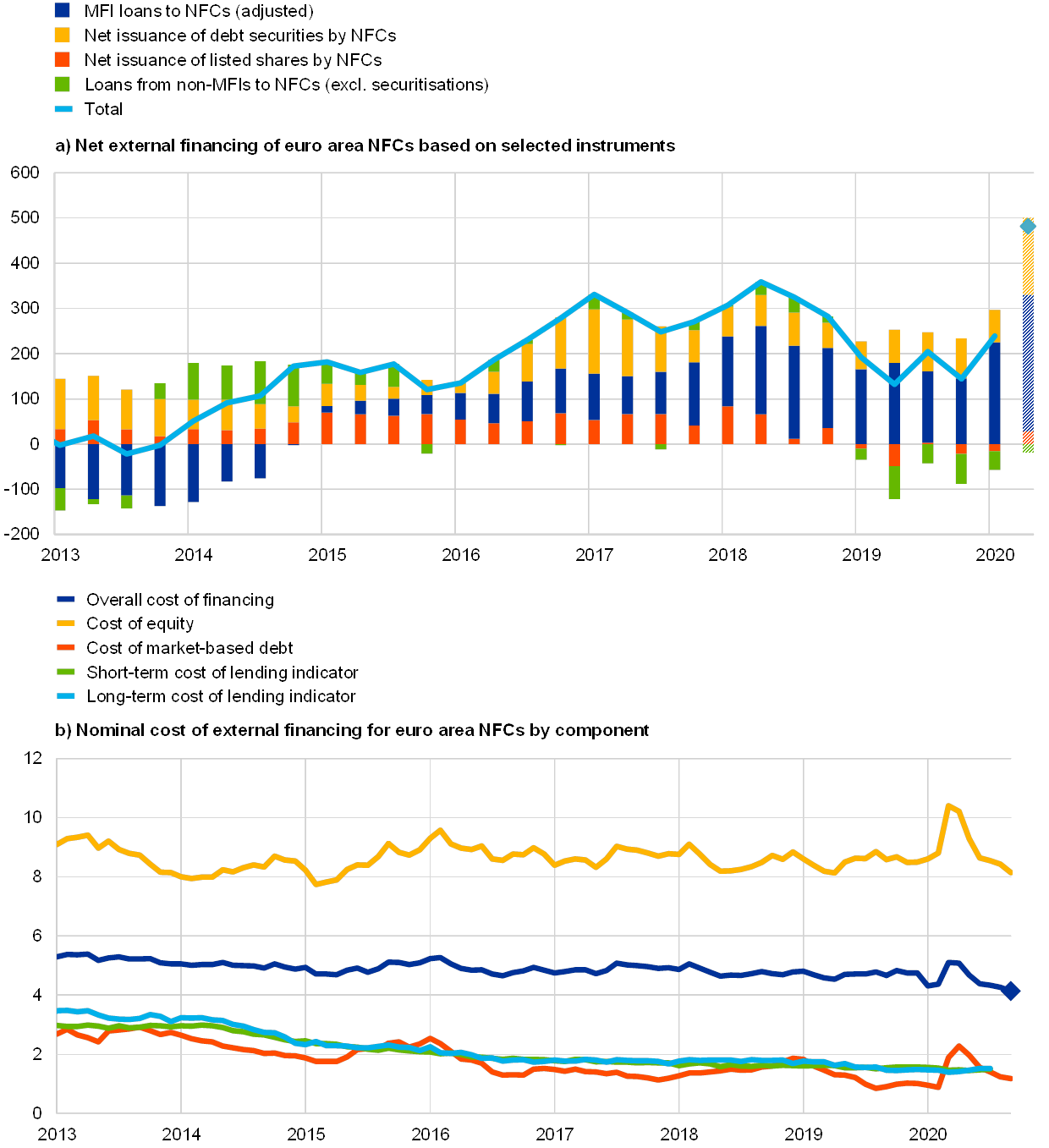

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has continued to bear a significant influence on monetary dynamics in the euro area. Domestic credit has remained the main source of money creation, driven by loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) and the Eurosystem’s net purchases of government bonds. The timely and sizeable measures taken by monetary, fiscal and supervisory authorities have supported the extension of bank credit on favourable terms to the euro area economy. This also buoyed euro area firms’ total external financing in the second quarter of 2020, as issuance of debt securities and bank lending to firms increased substantially. Firms’ overall cost of debt financing has remained favourable, as the cost of market-based debt has continued to moderate and bank lending rates have remained close to their historical lows.

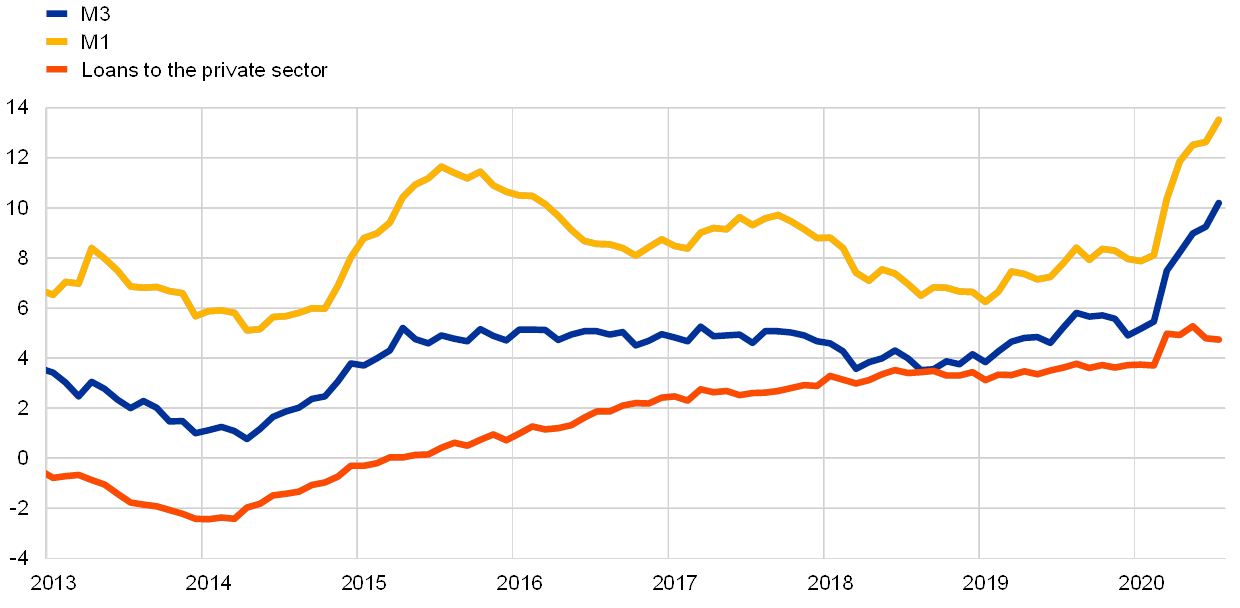

Broad money growth accelerated further in July. On account of a very large monthly flow, the annual growth rate of the broad monetary aggregate (M3) rose further in July, to 10.2%, from 9.2% in June. The shock from the pandemic significantly influenced monetary dynamics, as illustrated by M3 growth being around 5 percentage points higher than before the COVID-19 outbreak (see Chart 20). In an environment of elevated uncertainty, the demand for liquidity by economic agents was bolstered by the considerable liquidity needs of firms and the precautionary motives of all economic agents. Money demand models identify special factors related to firms’ and households’ liquidity needs during the pandemic as having made a significant contribution to broad money growth. The increase in money growth was also the result of sizeable support measures by monetary and fiscal policymakers, as well as actions taken by regulatory and supervisory authorities, to ensure sufficient liquidity in the economy to deal with the economic consequences of the pandemic. Moreover, the annual growth rate of the most liquid monetary aggregate, M1, which comprises overnight deposits and currency in circulation, rose to 13.5% in July, after 12.6% in June, and thus strongly contributed to M3 growth.

Chart 20

M3, M1 and loans to the private sector

(annual percentage changes; adjusted for seasonal and calendar effects)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Loans are adjusted for loan sales, securitisation and notional cash pooling. The latest observations are for July 2020.

Overnight deposits have seen a further upswing given the elevated uncertainty. The annual growth rate of overnight deposits, which was the main contributor to money growth, increased to 14.1% in July, from 13.1% in June. The growth in deposits was mainly driven by deposit holdings of firms. Money holders’ preference for overnight deposits continued to reflect precautionary motives and the very low level of interest rates, which reduces the opportunity cost of holding such instruments, especially when compared with other less liquid deposits. Furthermore, deposit holdings of firms varied across jurisdictions. This was partly related to the uneven and lagged spread of the pandemic across countries, which led to differences in the extent to which the liquidity needs of firms materialised. Differences in the size of support measures across countries also contributed to the uneven pace. Currency in circulation increased at a high, although broadly stable annual rate of 9.8% in July, reflecting a tendency to hoard cash given the substantial uncertainty. Other short-term deposits and marketable instruments made a small but increasing contribution to annual M3 growth in July, despite the low level of interest rates.

Domestic credit has remained the main source of money creation. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, credit growth to the private sector has remained at an elevated level (see the blue portion of the bars in Chart 21). Since 2018 this component has been the main driver of M3 growth from the counterpart perspective, with loans to non-financial corporations providing most of the momentum more recently. In addition, the Eurosystem’s net purchases of government securities under the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP) and the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) increased their sizeable contribution to M3 growth in July (see the red portion of the bars in Chart 21). The ECB’s non-standard monetary policy measures are providing enhanced monetary policy support to stabilise financial markets and to alleviate risks to monetary policy transmission and the euro area macroeconomic outlook during the pandemic. Furthermore, the annual growth rate of credit from the banking sector (excluding the Eurosystem) to the public sector remained strong in July (see the light green portion of the bars in Chart 21). Euro area banks (excluding the Eurosystem) acquired large amounts of government bonds, mainly issued in the euro area. It partly reflected the sizeable increase in net issuance of government debt to cope with the pandemic, which continued despite the announcement of additional measures at the EU level (such as the Next Generation EU package). After positive readings in May and June, monetary outflows from the euro area were moderate in July and reflected (net) sales of euro area sovereign bonds by non-residents (see the yellow portion of the bars in Chart 21). Furthermore, longer-term financial liabilities and other counterparts exerted a slightly negative impact on money growth (see the dark green portion of the bars in Chart 21).

Chart 21

M3 and its counterparts

(annual percentage changes; contributions in percentage points; adjusted for seasonal and calendar effects)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Credit to the private sector includes MFI loans to the private sector and MFI holdings of debt securities issued by the euro area private non-MFI sector. As such, it also covers purchases by the Eurosystem of non-MFI debt securities under the corporate sector purchase programme. The latest observations are for July 2020.