The euro area housing market during the COVID-19 pandemic

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 7/2021.

1 Introduction

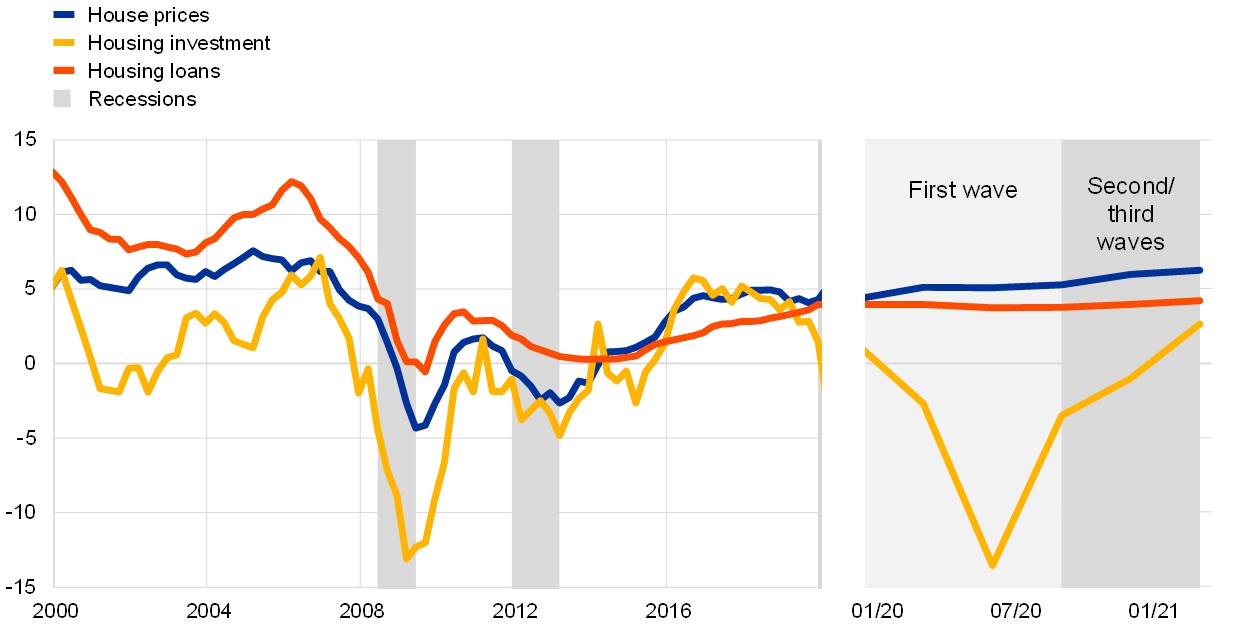

The euro area housing market was in a relatively long expansionary cycle before it entered the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis.[1] On the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, the euro area housing market was on solid ground. In the last quarter of 2019, house prices, housing investment and housing loans were on an upward trend, supported by robust income developments and bank lending rates for house purchases at historical lows (Charts 1 and 2).[2] Given the phase in which the housing cycle stood, an economic shock like the COVID-19 crisis might have been expected to turn the cycle.

Chart 1

House prices, housing investment and housing loans in the euro area

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB.

Note: Grey areas delimit recessions, as identified by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Euro Area Business Cycle Dating Committee.

However, the reaction of the euro area housing market to the COVID-19 crisis differed from that in previous crises owing to the different nature of the underlying shock.[3] The global financial crisis of 2008 originated in the US housing market and the sovereign debt crisis that started in 2010 stemmed primarily from financial shocks. Initially, the shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was unrelated to economic fundamentals and – especially in its early phases – afflicted the economy mainly through mandatory and voluntary restrictions on mobility aimed at containing the spread of the virus. These restrictions induced peculiar features compared with the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis, notably as a result of their diverse impact on real and nominal housing dynamics and differing housing developments across countries. The particular nature of the COVID-19 pandemic triggered vigorous monetary, fiscal and macroprudential policy responses.

This article explores the developments in the euro area housing market during the pandemic and compares them with those in previous crises, paying particular attention to the role of policy support measures. Throughout, the article takes a holistic approach that covers developments in and prospects for euro area housing investment, house prices and loans for house purchase. Section 2 focuses on the diverse impacts on the euro area housing market of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic from the first to the third quarter of 2020, when strict containment measures had the greatest effect on activity. Section 3 elaborates on the subsequent resilience of the housing sector through the second and the third waves of the pandemic up to the second quarter of 2021, amid more targeted containment measures and significant policy support measures. Section 4 provides a forward-looking perspective on the prospects and risks for the euro area housing market.

2 The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic – the diverse impacts of containment measures on the euro area housing market

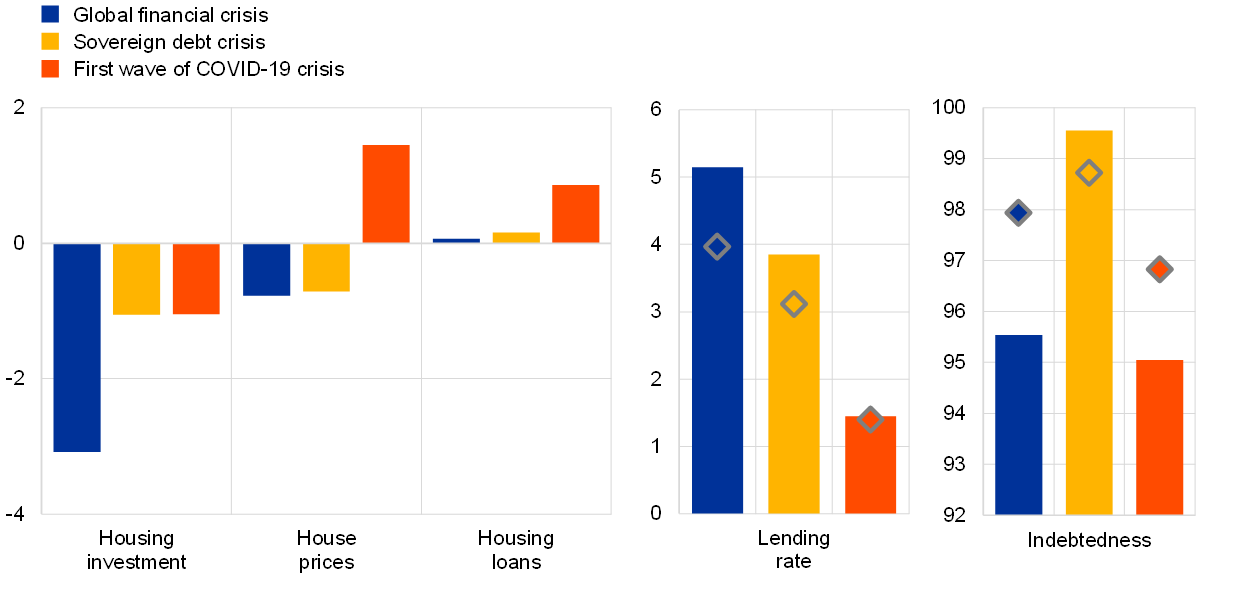

The containment measures in response to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic led to a divergence between real and nominal housing dynamics. The severe decline in mobility induced by containment measures and voluntary social distancing during the first wave of the pandemic had a negative impact on euro area housing investment, pushing it to 3.1% below its end-2019 level in the third quarter of 2020, broadly in line with the levels seen during the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis (Chart 2). However, while in the previous crises deteriorating economic fundamentals hampered growth in house prices and housing loans, the COVID-19 shock did not weigh on the upward trajectory of prices and loans, which surpassed their levels in the fourth quarter of 2019 by 4.3% and 2.6% respectively in the third quarter of 2020, supported by resilient housing demand amid policy support measures (Box 1).[4]

Chart 2

Euro area housing market developments in the global financial crisis, sovereign debt crisis and the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis

(percentage changes; lending rate and indebtedness as percentages)

Sources: Eurostat, ECB and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Lending rate refers to the composite lending rate on housing loans. Indebtedness refers to the ratio of housing loans to annual gross disposable income. All variables are computed as average percentage changes over the reference periods, except the lending rate and indebtedness, where the bars refer to their levels in the quarter before the reference periods and the diamonds refer to the level in the final quarter of the reference periods. The reference periods are defined in Section 1.

The different nature of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with previous crises is also visible in the larger degree of diversity in housing investment dynamics across countries. Losses in housing investment during the first three quarters of 2020 varied widely, with nine countries recording gains and two countries (Spain and Malta) incurring larger losses than during the global financial crisis (Chart 3). These heterogeneous dynamics can partly be explained by the timing and relative degree of restrictiveness of containment measures,[5] with construction activity being temporarily halted in some countries.[6] Other factors included the initial fiscal support measures, which varied considerably across countries in terms of scale and timing,[7] as well as the different demographic structures of the national housing markets.

Chart 3

Housing investment across euro area countries during the global financial crisis and the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis

(average percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and authors’ calculations.

Note: In the legend, variable “x” refers to the average percentage change in housing investment during the respective reference periods in each panel, as defined in Section 1.

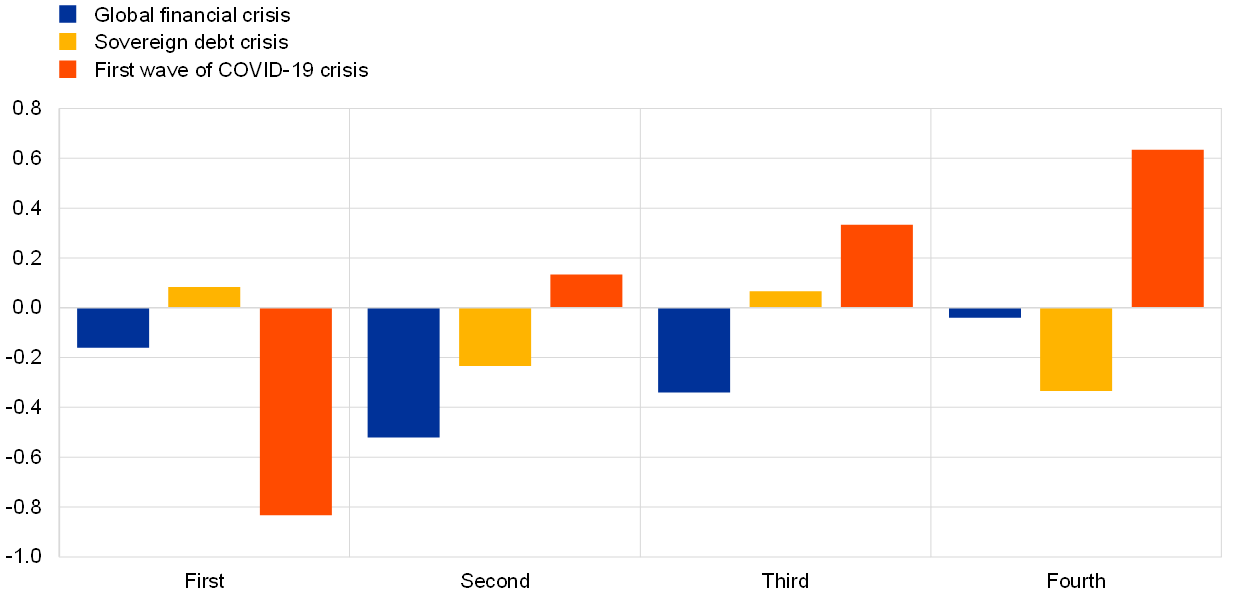

Demographic structures may also have induced diverse housing investment dynamics across countries, reflecting the differing impact of the first wave along the income distribution. Countries where a larger share of income is earned by poorer households experienced stronger declines in housing investment during the first wave of the pandemic.[8] Euro area survey data corroborates this, as lower-income households remained significantly less willing to purchase a house compared with pre-crisis levels by the end of the first wave of the pandemic in contrast to developments during the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis (Chart 4). Instead, the intentions of medium and higher-income households to purchase property increased. This most likely resulted from these income groups’ high levels of accumulated savings induced by restrictions on the consumption of high-contact services.[9]

Chart 4

Households’ intentions to purchase property across income quartiles in the global financial crisis, the sovereign debt crisis and the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis

(average changes; net balances)

Sources: European Commission and authors’ calculations.

Note: The reference periods are defined in Section 1.

Box 1

The impact of restrictions on mobility on the housing market – a structural approach

This box examines empirically the impact of mandatory and voluntary restrictions on economic agents’ mobility following the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on housing investment and house prices, accounting for several transmission mechanisms that are relevant for the housing market. On the basis of euro area aggregate data between the first quarter of 2000 and the first quarter of 2021, a Bayesian vector autoregression (BVAR) model exploits information from the dynamic interactions among seven endogenous variables: housing investment; real house prices; the composite lending rate on loans for house purchases; the stock of loans for house purchases; real GDP; consumer prices (HICP); and the shadow rate.[10] Following a large body of empirical literature,[11] the model identifies the main drivers of the housing market, imposing zero and sign restrictions on the co-movements among the endogenous variables upon the impact of various fundamental shocks.[12] To account for the specific characteristics of the COVID-19 crisis, the model includes – as an exogenous variable – a measure of the effective stringency of containment measures, namely the effective lockdown index. Conceptually, this index aims to isolate the economic impact of restrictions on mobility – accounting for both containment measures and voluntary social distancing – during the different waves of the pandemic.[13] In practice, the index acts as an augmented dummy variable, limiting the estimation problems induced by the abrupt and large fluctuations in economic developments observed since the start of the COVID-19 crisis.[14]

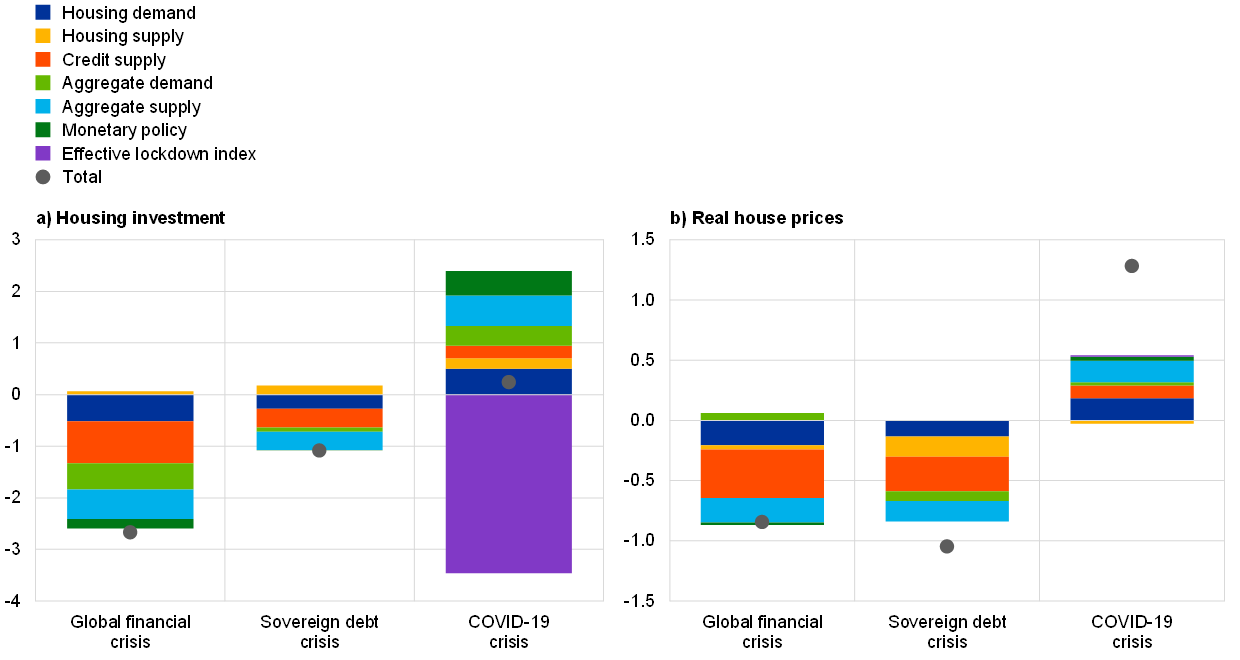

The historical decomposition of the drivers of housing investment and house prices highlights the peculiar effects of the COVID-19 crisis on the housing market (Chart A). During the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis, economy-wide shocks and housing market-related forces, such as housing demand and supply, as well as credit supply shocks, were behind the protracted decline in both housing investment and house prices. In contrast to the two preceding crises, economic fundamentals mostly supported both housing investment and house prices, on average, over the COVID-19 crisis. However, containment measures induced a dichotomy between real and nominal housing dynamics. In fact, effective restrictions on mobility significantly weighed on activity, while they left house prices relatively unaffected throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Over the COVID-19 crisis, the identified shocks can explain housing investment relatively well, but less so for house prices. The gap between actual and explained house prices is the result of unidentified factors, such as risk aversion and possible changes in preferences, and a positive average growth rate.

Chart A

Drivers of housing investment and real house prices during the global financial crisis, the sovereign debt crisis and the COVID-19 crisis

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes and percentage points)

Sources: Eurostat, Hale et al., op. cit., Lemke and Vladu, op. cit., Google residential mobility index, ECB, and authors’ calculations.

Notes: For comparability, the figures are reported as average quarter-on-quarter percentage changes and contributions over the reference periods, as defined in Section 1. The contribution of the constant term and other unidentified residuals (related for instance to risk aversion and possible changes in preferences) is not shown.

3 The second and the third waves – housing market resilience amid policy support measures

The housing market proved resilient during the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. In spite of the deterioration in the epidemiological situation that led to a tightening of restrictions in the fourth quarter of 2020, the euro area housing market gained further momentum. House prices remained on an upward trend, increasing in annual terms by around 6% in both the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, a pace not seen since mid-2007. Housing investment recovered further in the same reference period, settling close to its pre-crisis levels. These signs of significant resilience stemmed from both the supply side, as indicated by the momentum in value added and employment in construction and real estate, and the demand side, as suggested by the return of the number of transactions to pre-crisis levels in many euro area countries and the increased demand for mortgage loans. The milder impact of restrictions compared with the first wave and the significant stepping-up of fiscal and monetary policy measures, continuous favourable financing conditions, the increased attractiveness of housing for investment purposes – in view of forced savings – helped to strengthen housing investment and exert upward pressure on house prices.[15]

Fiscal policy measures were key in mitigating the negative effects of the second and the third waves of the pandemic on the housing market. These measures included short-time work schemes, targeted transfers to more vulnerable segments, cuts to personal income taxes, social contributions and indirect taxes. Policy interventions to support firms also contributed to mitigating the impact of the crisis on employment and income, and helped construction firms maintain housing supply.[16] These measures included direct support schemes for firms and the self-employed, partial compensation of losses, subsidies, tax deferrals and public guarantees on bank loans.[17] Other important policy tools were moratoria schemes, which provided households and firms with short-term relief through the suspension of principal and/or interest payments on loans, and very generous fiscal incentives for house renovation in some countries.

Monetary policy also provided key support to the euro area housing market by preserving favourable financing conditions for households and firms. First, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) announced in March 2020, by impacting yields especially at the long end of the maturity spectrum, exerted significant downward pressure on lending rates. This was particularly pronounced for mortgage rates, as they are typically linked to longer-term interest rates. Second, the negative interest rate policy continued to contribute to historically low lending rates, thereby supporting bank lending. Third, the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) offered attractive bank funding conditions, which banks passed on to firms and households, even for the non-targeted segment of the facility (i.e. housing loans).[18] Overall, according to the ECB bank lending survey (BLS), the ECB’s monetary policy measures contributed to an increase in housing lending volumes and an easing of bank lending conditions on new mortgages during the COVID-19 period.[19] As regards existing mortgages, households at the lower end of the income distribution seem to have benefited the most from the reduced interest rates via the so-called cash-flow effect of monetary policy, which increased their available resources for spending (Box 2).

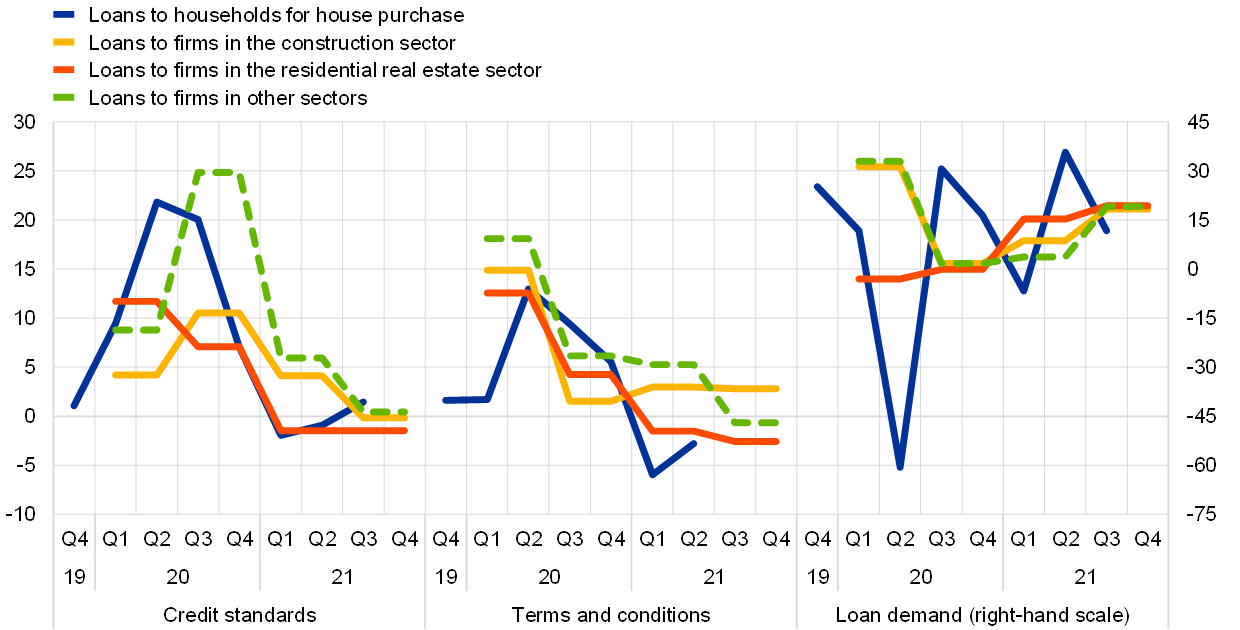

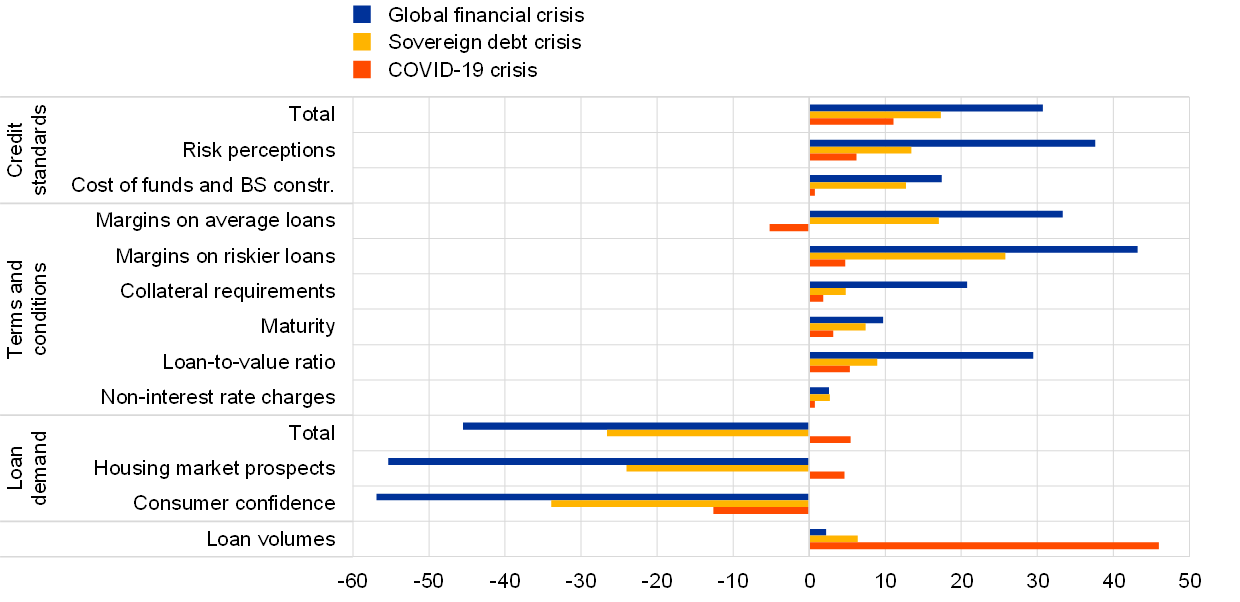

Financing conditions remained favourable, especially for less risky households, supporting the robust demand for housing. Apart from the first two months of 2020, flows of housing loans remained robust, with the annual growth rate of the loan stock reaching 4.2% in the first quarter of 2021, a rate not observed since 2008, significantly moving in tandem with house prices. Households’ demand for mortgages was met by historically low bank lending rates, which remained immune to the tightening in credit standards reported by banks in 2020 and to the increase in market rates in the first months of 2021. This muted response reflected favourable bank funding costs (buttressed by the policy support), but concealed a widening of lending margins for riskier borrowers and higher collateral requirements in the context of deteriorated perceptions of households’ creditworthiness. In the first half of 2021, tightening pressures on bank lending policies for housing loans vanished, primarily reflecting lower risk perceptions related to the improved economic outlook (Chart 5). The favourable developments observed during the second and third waves of the pandemic allowed households to experience a significantly smaller tightening of bank lending conditions during the COVID-19 period as a whole compared with previous crisis episodes (Chart 6).[20] The contribution of housing market prospects to loan demand was also strikingly different to that in previous crises in that it held up particularly well throughout the pandemic. Bank lending conditions for firms in the construction and the real estate sectors over the COVID-19 period were more favourable compared with those for firms in sectors that were hit harder by the containment measures.[21]

Chart 5

Bank lending conditions and loan demand for households and firms

(net percentages of banks)

Sources: ECB (BLS) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: The net percentages are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages for “tightened/increased considerably” and “tightened/increased somewhat” and the sum of the percentages for “eased/decreased somewhat” and “eased/decreased considerably”. “Loans to firms in other sectors” is the unweighted average of loans to firms in manufacturing, services, wholesale and retail trade and commercial real estate. For loans to firms by sector, the questions have a biannual frequency, hence banks report on two quarters at once instead of one. Q3 21 and Q4 21 denote expectations indicated by banks in the July 2021 BLS.

Chart 6

Bank lending conditions for housing loans, loan demand and loan volumes

(for BLS indicators: net percentages of banks, quarterly average over crisis episodes; for loan volumes: flows in EUR billions, quarterly averages over crisis episodes)

Sources: ECB (BLS), ECB (BSI) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: The net percentages are defined as the difference between the sum of the percentages for “tightened/increased considerably” and “tightened/increased somewhat” and the sum of the percentages for “eased/decreased somewhat” and “eased/decreased considerably”. “Risk perceptions” is the unweighted average of “general economic situation and outlook” and “housing market prospects, including expected house price developments”. “Cost of funds and BS constr.” stands for “Cost of funds and balance sheet constraints”.

In a context of low interest rates, high uncertainty and large savings, housing demand has also been supported by investment motives. The demand for housing for investment purposes has been a distinctive feature of the recovery in housing markets that started in 2013.[22] This factor seems to have strengthened during the COVID-19 period, reflecting a further increase in the relative attractiveness of housing as an investment class and a further expansion of the availability of savings amid considerable economic uncertainty.[23] [24] Moreover, flows into real estate funds, albeit declining slightly in 2020, remained at relatively high levels, also as a share of residential investment. Although some of these funds could also be directed to commercial real estate or outside the euro area, this evidence suggests that private and institutional investors searching for yield and safety may have contributed to additional housing demand during the COVID-19 period.

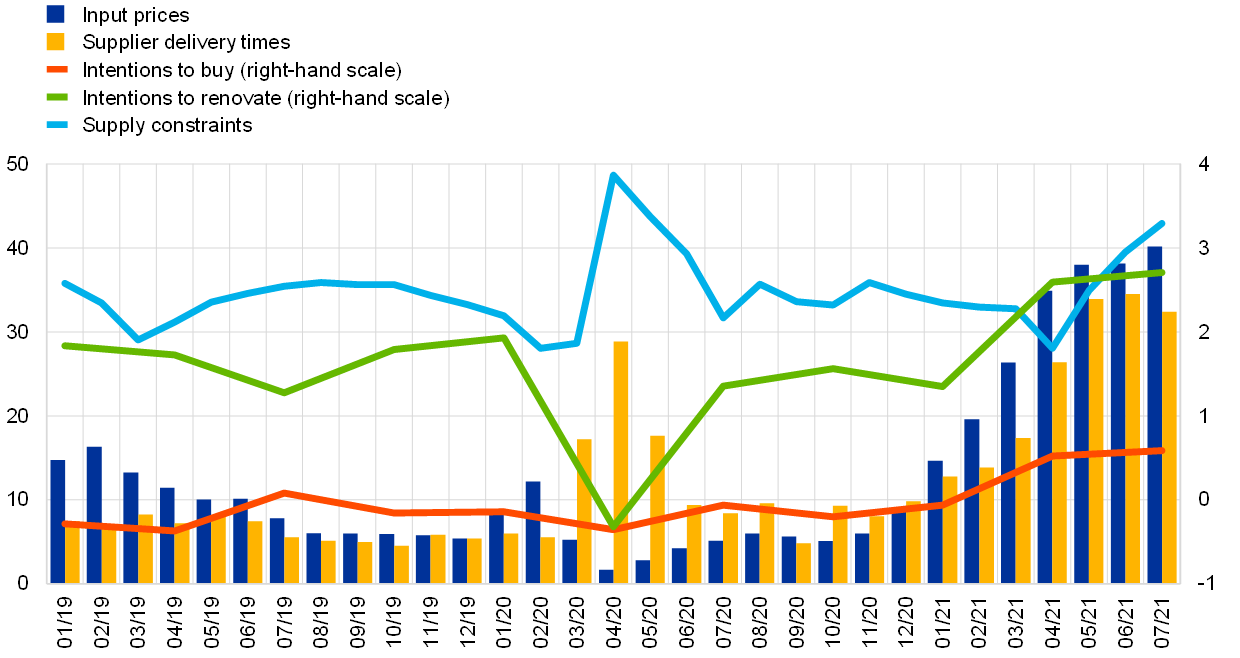

Supply-side constraints have also exerted upward pressures on house prices. Constraints on housing supply have been an important factor behind housing market dynamics over the 2013-19 period. Following the significant decline in building permits in the aftermath of the pandemic outbreak, supply bottlenecks were further aggravated during the different waves of the pandemic (Chart 7). While in the first wave financing conditions and other factors (notably, containment measures) particularly constrained production, in the second and third waves supply bottlenecks were mainly due to labour and material shortages. The lack of (especially high-skilled) workers was also a major factor limiting production before the COVID-19 crisis,[25] but the shortage of materials reflected global supply-chain disruptions and a reallocation of resources induced by the outbreak of the pandemic, leading to increases in supplier delivery times and input costs. Overall, survey data suggest that, for construction firms, supply-side constraints increased relative to demand constraints during the COVID-19 period.

Box 2

Monetary policy and the cash-flow effect on households via mortgages

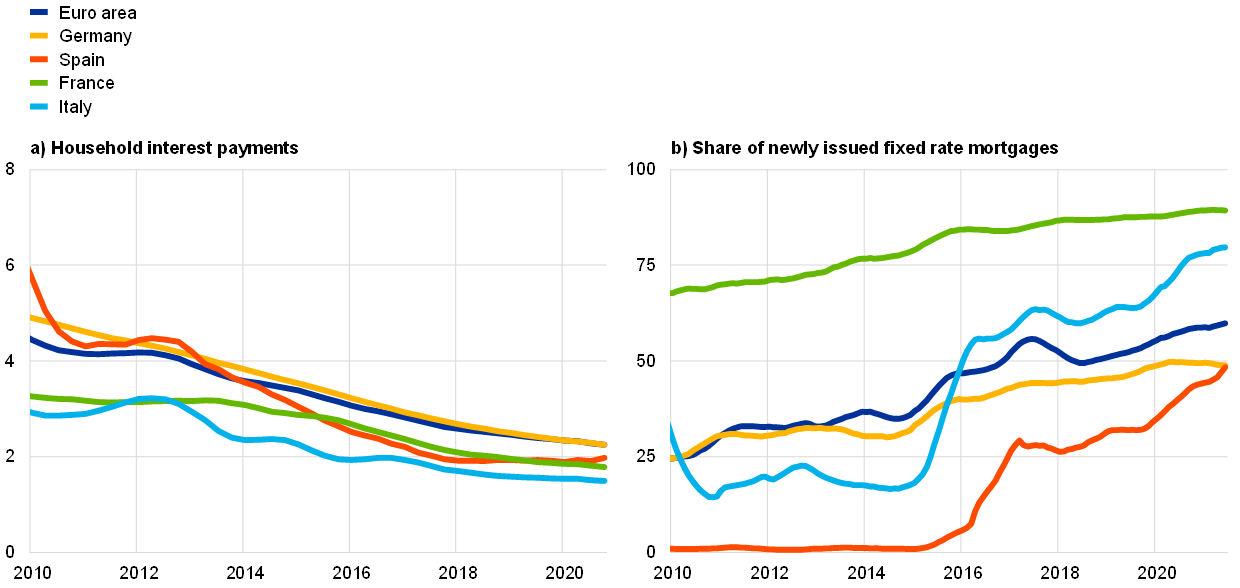

This box assesses the benefit households received from lower interest payments on their existing mortgage debt since the beginning of the ECB’s unconventional monetary policy in 2015. This so-called cash-flow effect of monetary policy contributed to the decrease in interest payments of the aggregate euro area household sector, which overall reached a record low of 2.2% of disposable income at the end of 2020 (Chart A, panel a). This positive effect helped households deal with the COVID-19 shock.

Chart A

Household interest payments and fixed rate mortgages

(panel a): percentages of gross disposable income; panel b): percentages)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB quarterly sectoral accounts (QSA) and ECB monthly data on euro area interest rates on loans and deposits (MIR).

Notes: Panel a): actual gross interest payments, i.e. including FISIM (financial intermediation services indirectly measured). Panel b): 12-month moving average of the share of new loans for house purchase with initial fixation period above ten years in total new loans for house purchase.

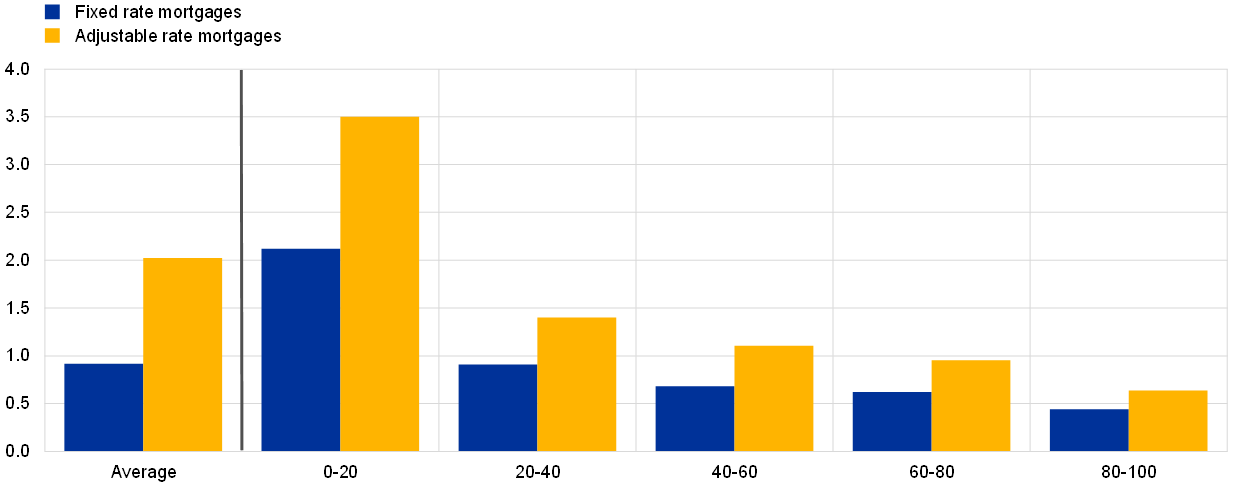

To investigate the distributional impact of this monetary policy transmission channel, we calculate the size of the advantage across the income distribution of households with a mortgage. Furthermore, we differentiate between the impact via adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs), which are relinked periodically to the change in short-term rates, and fixed rate mortgages (FRMs), which are affected by the change in long-term rates if households engage in refinancing their mortgage. Given the relatively large decrease in long-term rates since 2015 and the rising share of FRMs (Chart A, panel b), the advantage obtained via this channel is likely to have increased.

We calculate the benefit across the joint income distribution of households with a mortgage in the five largest euro area economies, combining household-level information on mortgages and income with country-level information on interest rates. Considering all households with a mortgage in 2014 (based on the second wave of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS)), we calculate the income gain they booked at the end of 2020 compared with their initial situation in 2014 as a result of lower interest payments on their mortgages. For ARMs, calculations are based on developments in the short-term rate (EURIBOR 3-month), while for FRMs,[26] they take into account developments in long-term interest rates and refinancing volumes. In general, the latter increase with the size of the interest advantage, i.e. with the gap between long-term rates on new mortgages and the rate on outstanding ones.

Chart B

Income gain through lower interest payments on mortgages by income percentile

(percentages of household gross income)

Sources: ECB (HFCS, MIR) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: The chart shows, for the households with a mortgage in 2014 in Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the Netherlands and grouped according to the aggregate income quintiles over those countries (x-axis), the average income gain booked at the end of 2020 compared with the initial situation in 2014 as a result of lower interest charges on adjustable (ARMs) and fixed rate mortgages (FRMs). For ARMs, this is calculated by the change in the short-term rate (EURIBOR 3-month) times the value of the outstanding ARMs in 2014. The gain due to lower interest rates on FRMs is calculated by the product of three components: the outstanding amount of FRMs in 2014, the average share of households that renegotiated their loans over the period 2015-20, and the average interest advantage they booked computed as the average difference between renegotiated rates and the rates on new mortgages five years earlier.

The cash-flow effect benefited all households with a mortgage and was on average around 0.9% of gross income via FRMs and 2% via ARMs (Chart B), supporting – all else being equal – household balance sheets, including during the COVID-19 period.[27] In the latter period, the income gain might have taken the form of extra savings, contributing to the resilience of the housing market.[28] Furthermore, the cash-flow effect benefited low income households in particular, which were most exposed to labour income losses during the COVID-19 period.[29] As such, lower interest payments might have mitigated the overall negative impact on the income of debtors, thereby also dampening inequality forces,[30] the likelihood of payment arrears and the need to make extensive and prolonged recourse to moratoria.[31] Finally, lower long-term rates encouraged both refinancing and a higher share of FRMs, so that households have been able to lock in the low interest rates, enhancing their debt sustainability and reducing their interest sensitivity in the event that monetary policy tightens.

4 Prospects and risks for the euro area housing market

Several factors are likely to support housing market prospects in the near term. The expected recovery in economic activity – sustained by a successful vaccination campaign in the euro area – should hold up households’ income and employment prospects, including when fiscal support gradually recedes. Financing conditions are likely to remain favourable, reflecting the policy support and the expected improvements in borrowers’ creditworthiness. Recent lending dynamics and indications from the BLS, which tend to display good leading properties in around two to three quarters in terms of house prices and housing investment, point to continued dynamism in the housing market in the coming quarters. Housing investment is likely to continue its positive trend observed since the third quarter of 2020, reinforced by resilient house prices relative to construction costs, improving real disposable incomes and buoyant intentions to buy and renovate properties (Chart 7). In addition, a part of the savings accumulated during the pandemic could be redirected into the housing market amid a low-yield environment and the increased relative attractiveness of housing for investment purposes. The share of residential property in real estate portfolios is likely to increase since it is perceived as a safer asset in times of uncertainty (housing is a primary need) entailing stable income streams (rents).

Nevertheless, the outlook for the housing market remains highly dependent on uncertainties related to the pandemic. Adverse developments related to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the possible spread of new variants, might weigh on housing market prospects, and particularly on housing demand, as observed at the beginning of the pandemic. Amid high uncertainty, the withdrawal of policy support measures is an additional factor that could possibly limit prospects for the housing market if such policies were to be phased out before the recovery is on track. In addition, the overall increase in risk-free interest rates observed since the beginning of 2021 may exert upward pressure on mortgage rates. Moreover, the developments in shortages of raw materials and the associated increases in supplier delivery times and input costs could negatively affect construction activity and exert strong upward pressure on prices in the near term (Chart 7). This would contribute to keeping house prices in the euro area at an elevated level,[32] thus possibly increasing the importance of and need for macroprudential measures (Box 3).

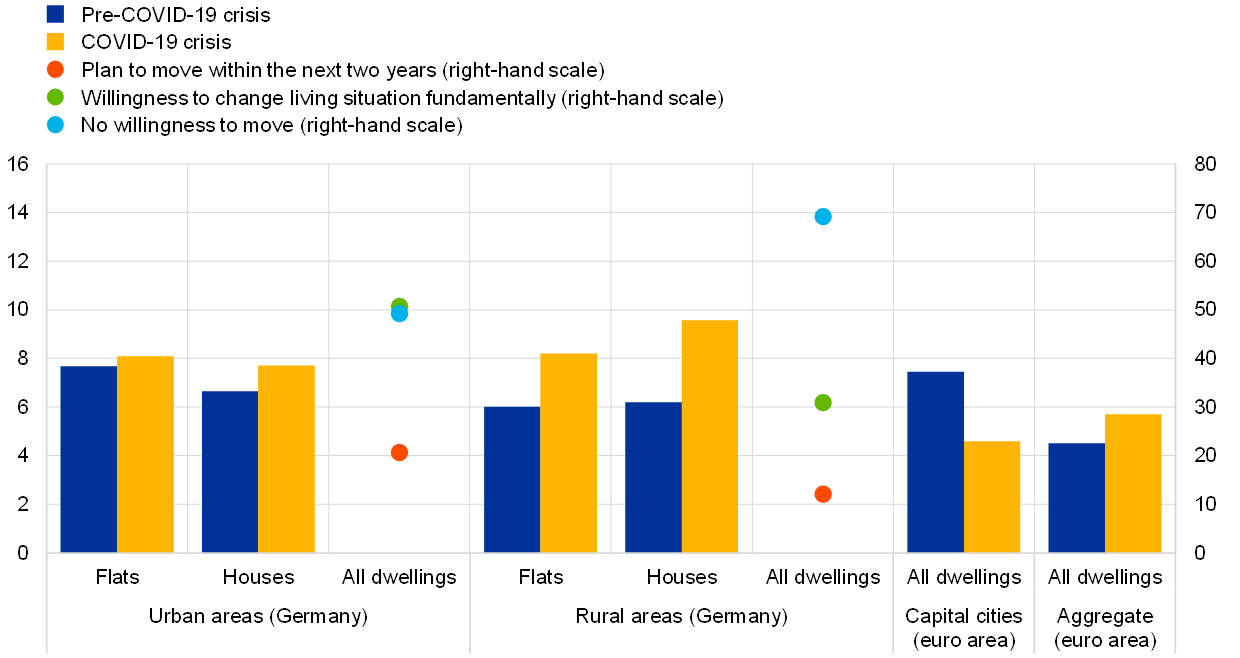

Chart 7

Euro area supply constraints, construction input prices, supplier delivery times and intentions to buy and renovate

(input prices and supplier delivery times: deviation from baseline (50); intentions to buy and renovate: standardised levels; supply constraints: levels)

Sources: European Commission, IHS Markit and own calculations.

Changes in housing preferences may also affect the housing market going forward. The COVID-19 pandemic may bring changes in preferences and behaviour that could influence housing demand over the medium-to-long term. Should work-from-home arrangements become more prevalent, housing demand may partly shift away from city centres towards suburban and rural areas, as the opportunity costs associated with peripheral working places would decrease in tandem with commuting time.[33] This could contribute to limiting upward pressure on rent and house prices in large cities characterised by limited housing supply. As observed in other advanced economies,[34] preliminary evidence for some euro area countries tends to corroborate this narrative, hinting, for example, at buoyant house prices in rural areas in Germany and softening house price increases in capital cities in the euro area compared with the pre-pandemic period (Chart 8).[35] [36] The accelerated introduction of remote working arrangements slowed down the demand for commercial office and retail spaces, potentially opening up the possibility to convert some of these properties into residential housing in areas where supply is limited.[37] Both climate change and climate policies could also affect the housing market going forward. Investment in the energy efficiency of buildings could boost housing investment – also helped by fiscal incentives in some countries – thus lowering household spending on energy. In addition, properties meeting enhanced energy credentials could command higher prices, thus posing additional challenges for housing affordability.

Chart 8

Households’ plans to move and price developments in urban areas vis-à-vis rural areas

(average growth rates; percentages)

Sources: ECB, DESTATIS, ifo Institute, Eurostat, national sources and own calculations.

Notes: Residential property prices for urban areas in Germany are calculated as average growth rates of metropolis, cities not attached to a district and urban districts, and for rural areas, as average growth rates of densely and sparsely populated rural districts. The pre-COVID-19 period spans from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2019, and the COVID-19 crisis period runs from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. The “willingness to move” of households living in urban areas is calculated as the average of households’ responses from urban areas, suburban areas and small cities expressed as a percentage to a survey by the German ifo Institute. The “plan to move within the next two years” is calculated as the sum of percentages of households planning to move within the next six months, six to twelve months and within the next two years. The euro area aggregate series is a weighted average based on GDP weights, which includes Belgium, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Slovenia and Finland.

Box 3

Macroprudential policy for residential real estate before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic

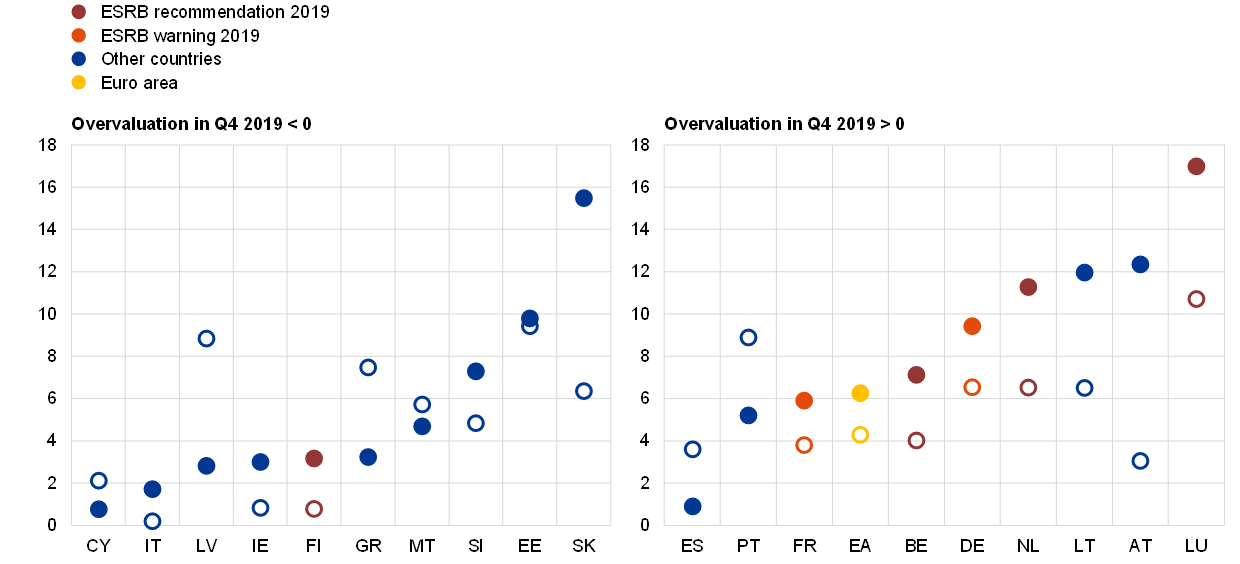

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many euro area countries had activated macroprudential measures to address the build-up of residential real estate (RRE) vulnerabilities or to act as a prudent backstop. At the beginning of 2020, 14 euro area countries had in place borrower-based macroprudential measures (BBMs), such as loan-to-value (LTV), debt-service-to-income (DSTI), debt-to-income (DTI) or maturity limits.[38] In addition, seven euro area countries had activated macroprudential risk weight policies to increase the amount of capital banks need to hold against mortgage loans.[39] BBMs were put in place by many countries to act as a prudent backstop for lending standards, affecting only a small fraction of mortgage loan origination at the time of implementation, but providing an automatic limit to a potential widespread loosening of lending standards in the future. However, in some countries RRE vulnerabilities had been building up over preceding years, leading the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) to issue warnings and recommendations to six euro area countries in September 2019.[40] In some countries, macroprudential measures were therefore put in place to more actively contain the build-up of RRE vulnerabilities and increase bank resilience against associated systemic risks.

Following the outbreak of the pandemic, in line with the countercyclical nature of macroprudential policy, some national authorities eased macroprudential measures for RRE in order to limit the possible amplification effects of a tight macroprudential stance. In Malta, Portugal, Slovenia and Finland, national authorities adjusted existing BBMs at the height of the pandemic in spring 2020, fearing that the pandemic shock could constrain market access for solvent borrowers facing temporary income and liquidity shocks.[41] Two countries provided some capital headroom to absorb losses and meet credit demand. In the Netherlands, the planned implementation of an LTV-dependent risk weight floor for mortgage loans was postponed, and, in Finland, the existing risk weight floor for IRB mortgage loans was not extended beyond 2020. All of the above measures provided relief to new borrowers and banks alike and complemented other support measures, such as loan repayment moratoria or short-term working schemes (Section 3).

In most euro area countries, authorities did not adjust the BBMs that were already in place, as they were considered to be prudent back-stops for which adjustment had not been foreseen throughout the cycle. In addition, depending on the legal basis, there was a possibility that adjusting BBMs might involve lengthy processes compared with capital measures. However, Belgium and Estonia extended the application of risk weight measures on mortgages (under Article 458 of the CRR) in 2021 to retain bank resilience for accumulated RRE risks. Since existing risk weight measures affect minimum requirements or sectoral buffers, they might need to be released in the event that risks and losses in the RRE market materialise.

Chart A

Macroprudential measures should be considered in countries where vulnerabilities continue to build up as short-term downside risks recede

a) Annual RRE price growth in the fourth quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2021

(panel a): percentages; panel b): current policy considerations for RRE macroprudential measures)

b) Current policy considerations for RRE macroprudential measures

Sources: ECB and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Panel a): Hollow dots refer to the values in the fourth quarter of 2019; coloured dots refer to the values in the first quarter of 2021 (the fourth quarter of 2020 for Cyprus and Finland). Average overvaluation denotes the average of the price-to-income ratio and the results of an econometric model in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Going forward, as pandemic risks recede, further macroprudential measures for RRE should be considered in countries where RRE vulnerabilities continue to build up. Robust house price and mortgage loan growth continued throughout the pandemic, particularly in countries with pre-existing RRE vulnerabilities (Chart A, panel a). Nevertheless, the divergence between the RRE and economic cycles during the COVID-19 pandemic can imply downside risks in adverse growth scenarios, especially if government support is scaled back too early. In this context, macroprudential measures should be used in countries where vulnerabilities continue to build up as short-term downside risks recede (Chart A, panel b). In this regard, Luxembourg activated BBMs at the end of 2020, while in spring 2021 the Netherlands confirmed its intention to activate the LTV-dependent risk weight floor for mortgage loans.[42] These actions notwithstanding, further macroprudential measures could be needed in some euro area countries if current trends in RRE markets continue.

5 Conclusion

This article discussed developments in the euro area housing market since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The mandatory and voluntary restrictions on economic agents’ mobility in response to the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic had a strong impact on activity without significantly impairing the upward trend in prices and loans, in contrast to the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis. Moreover, the first wave of the pandemic induced greater diversity in housing investment across countries compared with previous crises, which is partly explained by the varying impact of restrictions along the income distribution.

Several factors supported the housing sector throughout the pandemic. The resilience of the housing market originated in part from the declining impact of restrictions after the first wave. Other factors included fiscal, monetary and macroprudential policy measures, continuously favourable financing conditions, the increased attractiveness of housing for investment purposes, as well as supply-side bottlenecks exerting upward pressure on house prices without significantly weighing on activity.

Overall, pandemic-related uncertainties and associated structural changes will continue to influence the prospects for the housing market. The broad-based economic recovery and the use of the large stock of accumulated savings are likely to support housing market prospects going forward. However, the outlook remains uncertain and depends on how the pandemic develops and the timing of the withdrawal of policy support. Changes in housing preferences may also lead to a reallocation within the housing market, away from commercial and urban residential properties and towards suburban and rural residential real estate. Heterogeneous developments across households are likely to persist and possibly intensify.

- For an assessment of the state of the euro area housing market before the COVID-19 pandemic, see the article entitled “The state of the housing market in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB, 2018.

- Throughout this article, unless otherwise indicated, house prices refer to the nominal house price index, housing investment to real investment in residential construction and housing loans to loans to households for house purchases in nominal terms.

- Throughout the article, in line with the chronology of euro area business cycles established by the CEPR Euro Area Business Cycle Dating Committee, unless otherwise stated, we refer to the COVID-19 crisis as the period between the fourth quarter of 2019 (pre-crisis peak) and the latest available quarter (since no end date has yet been set). The global financial crisis refers to the period between the first quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2009, while the sovereign debt crisis refers to the period between the third quarter of 2011 and the first quarter of 2013.

- For an analysis of developments in euro area house prices and their relation to macroeconomic conditions along different dimensions, see the box entitled “Euro area house price developments during the coronavirus pandemic”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2021.

- The stringency of containment measures, proxied by the Oxford stringency index, explains around 25% of the total cross-country variation in housing investment levels over the first three quarters of 2020. For the Oxford stringency index, see Hale, T., Angrist, N., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Kira, B., Majumdar, S., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Tatlow, H. and Webster, S., “Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker,” Blavatnik School of Government, 2020.

- See the study entitled “Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on EU industries”, European Parliament, March 2021; the box entitled “The impact of containment measures across sectors and countries during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2021; the box entitled “The heterogeneous economic impact of the pandemic across euro area countries”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2021, and the references therein.

- See, for example, “The initial fiscal policy responses of euro area countries to the COVID-19 crisis”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2021.

- This is obtained controlling for time- (quarterly-) fixed effects and the stringency of containment measures, as proxied by the Oxford stringency index based on the first three quarters of 2020 for euro area countries.

- Indeed, the strong rebound of intentions to purchase property for medium and higher-income households (in contrast to lower-income households) in response to the easing of containment measures at the end of the first wave of the pandemic followed the large increase in savings in the early phases of the pandemic, in line with evidence from the Consumer Expectations Survey (CES). See the box entitled “COVID-19 and the increase in household savings: an update”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2021. According to CES data, higher-income homeowners reported less pressing financial concerns and more buoyant house purchases in the third quarter of 2020. See Christelis, D., Georgarakos, D., Jappelli, T. and Kenny, G., “The COVID-19 crisis and consumption: survey evidence from six EU countries”, Working Paper Series, No 2507, ECB, December 2020.

- All the variables are quarter-on-quarter percentage changes, except for the lending and the shadow rates, which are quarter-on-quarter changes. The shadow rate is taken from Lemke, W. and Vladu, A. L., “Below the zero lower bound: a shadow-rate term structure model for the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 1991, ECB, January 2017.

- Among studies that include the euro area, see Smets, F. and Jarociński, M., "House prices and the stance of monetary policy", Working Paper Series, No 891, ECB, April 2008; Bijsterbosch, M. and Falagiarda, M., “Credit supply dynamics and economic activity in euro area countries: A time-varying parameter VAR analysis” , Working Paper Series, No 1714, ECB, August 2014; Gambetti, L. and Musso, A., “Loan Supply Shocks and the Business Cycle”, Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 32, Issue 4, 2017, pp. 764-782; Nocera, A. and Roma, M., “House prices and monetary policy in the euro area: evidence from structural VARs”, Working Paper Series, No 2073, ECB, June 2017; and Altavilla, C., Darracq Pariès, M. and Nicoletti, G., “Loan supply, credit markets and the euro area financial crisis”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 109, December 2019.

- The housing demand and supply shocks are identified based on the contemporaneous reaction by housing investment and house prices, which are assumed to move in the same direction for housing demand shocks and in opposite directions for housing supply shocks. Housing demand and credit supply shocks differ, as they imply opposite reactions in the lending rate, while housing investment and house prices co-move positively in response to both shocks. Expansionary aggregate demand shocks induce an increase in real GDP, consumer prices and the shadow rate, while expansionary aggregate supply shocks lead to an increase in real GDP and a decline in consumer prices. A monetary policy loosening induces a decline in the lending and the shadow rates and puts upward pressure on housing investment, house prices, real GDP and consumer prices. Housing-related shocks are assumed to have no contemporaneous impact on aggregate variables, i.e. real GDP, consumer prices and the shadow rate. The model includes one unidentified shock to capture the effects of any further remaining disturbances. For technical details on the implementation, see Arias, J. E., Rubio-Ramírez, J.F. and Waggoner, D. F., “Inference Based on Structural Vector Autoregressions Identified With Sign and Zero Restrictions: Theory and Applications”, Econometrica, Vol. 86, Issue 2, 2018, pp. 685-720.

- The effective lockdown index is constructed multiplying the Oxford stringency index (Hale et al., op. cit.) by the Google residential mobility index, which closely reflects the dynamics in footfall related to work-from-home arrangements, identified as being among the main drivers of the process of learning by economic agents, and explaining the cross-sectoral heterogeneity in the impact of containment measures over the different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. See the box entitled “The impact of containment measures across sectors and countries during the COVID-19 pandemic”, op. cit. Results are qualitatively robust to the use of alternative Google mobility measures.

- See Lenza, M. and Primiceri, G., “How to estimate a VAR after March 2020”, Working Paper Series, No 2461, ECB, August 2020.

- For more details, see “The impact of containment measures across sectors and countries during the COVID-19 pandemic”, op. cit.

- Under short-time work schemes, firms experiencing economic difficulties could temporarily reduce the hours worked while providing their employees with income support from the government for the hours not worked.

- For more details on the fiscal policy measures implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, see “The initial fiscal policy responses of euro area countries to the COVID-19 crisis”, op. cit. and “Public loan guarantees and bank lending in the COVID-19 period”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2020.

- Moreover, from a microprudential policy perspective, ECB Banking Supervision provided important capital relief for banks, which created further space for bank balance sheet expansion.

- See Section 3 of the April 2021 ECB bank lending survey (BLS).

- Previous crises had a more direct impact on the banking sector, which went through a process of significant balance sheet adjustment. This process constrained banks’ intermediation capacity, resulting in tighter lending policies.

- As with other sectors, firms in the construction and real estate sectors reduced their recourse to bank financing in the second half of 2020 on account of abated emergency liquidity needs and the significant precautionary buffers built up in the early stages of the pandemic (see Falagiarda, M. and Köhler-Ulbrich, P., “Bank lending to euro area firms – What have been the main drivers during the COVID-19 pandemic?”, European Economy: Banks, Regulation, and the Real Sector, Vol. 1, 2021, pp. 119-143). Moreover, during this period, loan demand continued to be dampened by high uncertainty, especially for the financing of fixed investment. In the first half of 2021, firms in the construction and real estate sectors started to significantly increase their demand for bank borrowing (Chart 6) owing to the improved economic outlook and robust demand for housing.

- See the article entitled “The state of the housing market in the euro area”, op. cit.

- The impact of the forced accumulation of savings associated with the pandemic is discussed in the box entitled “The recovery of housing demand through the lens of the Consumer Expectations Survey” of this issue of the Economic Bulletin.

- Estimates of the return on housing-related investment point to an increase in the relative attractiveness of investment in residential property vis-à-vis government bonds and deposits during the COVID-19 period. Increased housing returns may have in turn fuelled higher house price expectations, thereby further boosting the demand for housing.

- See, for instance, the KfW-ifo Skilled Labour Barometer for German construction in June 2021.

- We consider all housing loans with an initial rate fixation period over ten years as FRMs, although these may allow for rate changes after this period which resemble ARM properties (e.g. rate changes every five years after the first ten years).

- Note that the part of these gains related to unconventional monetary policy would require the identification of the monetary policy shock. Such exercises confirm the larger effect via ARMs than via FRMs. See, for example, Pietrunti, M. and Signoretti, F. M., “Unconventional monetary policy and household debt: The role of cash-flow effects”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Vol. 64, No 103201, June 2020. Similar to the methodology used here, Ehrmann, M. and Ziegelmeyer, M., “Mortgage choice in the euro area: Macroeconomic Determinants and the effect of monetary policy on debt burdens”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 49, March-April 2017, pp. 469-494 find that the largest impact is via ARMs, although these results date back to the period before the existence of unconventional monetary policy.

- Given forced savings, marginal propensities to consume have been relatively low during the COVID-19 pandemic. See the box entitled “COVID-19 and the increase in household savings: precautionary or forced?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, ECB, 2020; and Christelis, D., Georgarakos, D., Jappelli, T. and Kenny, G., “The COVID-19 crisis and consumption: survey evidence from six EU countries”, op. cit.

- See Schnabel, I., “Unequal scars – distributional consequences of the pandemic”, speech at the panel discussion “Verteilung der Lasten der Pandemie” (“Sharing the burden of the pandemic”), Deutscher Juristentag 2020, Frankfurt am Main, 18 September 2020 and the references therein.

- See the article entitled “Monetary policy and inequality”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2021.

- The positive impact of the cash-flow effect via mortgages on households goes hand-in-hand with a negative effect on banks’ balance sheets. However, positive effects on banks’ balance sheets also arise as a result of the improved creditworthiness of households. For a study on the overall impact of monetary policy on banks’ profitability, see Altavilla, C., Bouchina, M. and Peydró, J.L., “Monetary policy and bank profitability in a low interest rate environment”, Economic Policy, Vol. 33, Issue 96, October 2018, pp. 531-586.

- For further details, see the ECB’s Financial Stability Review May 2021.

- According to a survey by the German ifo Institute “Wie beeinflusst die Corona-Pandemie die Wohnortpräferenzen?”, ifo Schnelldienst, Vol. 74, No 08, 2021, around 20% of households living in urban areas plan to move within the next two years in contrast to a share of 12% of households living in rural areas planning to move (Chart 8). For almost half of these respondents (46%), their decision was influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- For further details, see “How Covid Has Reshaped Real Estate From New York to Singapore”, Bloomberg, May 2021 and “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Demand for Density: Evidence from the U.S. Housing Market”, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, August 2020,, which show that in the United States the pandemic has led to a shift in housing demand away from neighbourhoods with high population density.

- For further details, see the box entitled, “Euro area house price developments during the coronavirus pandemic”, op. cit.

- In March 2021 Ireland launched a plan to create a network of more than 400 remote working hubs, introducing tax breaks for individuals and companies which support work-from-home arrangements and launching a Rural Development Policy for the period 2021-25.

- For further details, see “Brick by Brick”, OECD, May 2021.

- The only euro area countries without BBMs in place at the beginning of 2020 were Germany, Greece, Spain, Italy and Luxembourg. Details on the BBMs implemented across countries can be found in Section 4 of Lang, J.H, Pirovano, M., Rusnák, M. and Schwarz, C., “Trends in residential real estate lending standards and implications for financial stability”, Special Feature A, Financial Stability Review, European Central Bank, May 2020.

- Risk weight policies affect capital ratios by increasing risk weights on banks’ exposures to residential real estate. This generally results in higher risk-weighted exposures and implies that additional capital is needed to meet capital requirements. Belgium, Estonia and Finland had activated risk weight multipliers, add-ons and floors under Article 458 of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) for domestic residential mortgage loans of banks using the internal ratings-based approach (IRB) to determine risk weights. Ireland, Malta and Slovenia had activated risk weight floors under Article 124 of the CRR for mortgage loans of banks using the standardised approach (STA) to determine risk weights. Luxembourg had recommendations in place regarding risk weight floors for mortgages under both the STA and IRB approaches.

- Germany and France were subject to a warning by the ESRB, while Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Finland received ESRB recommendations. See ESRB Press Release, “ESRB issues five warnings and six recommendations on medium-term residential real estate sector vulnerabilities”, 23 September 2019.

- In Portugal, in April 2020, it was decided that personal credit with maturities of up to two years will not need to comply with DSTI limits and is exempted from the recommendation of regular principal and interest payments until September 2020. In Slovenia, an amendment of the macroprudential restrictions on household lending to provide temporary flexibility when calculating income was implemented in May 2020. In Finland, the LTV/C limit for other than first-time buyers was restored from 85% to 90% in June 2020. In Malta, an extension of the phasing-in period for the LTV limit and the adoption of a temporary relaxation of the stressed DSTI limit of 40% was implemented in June 2020.

- The measure is expected to enter into effect on 1 January 2022, provided that the economic recovery continues in line with current expectations (DNB Financial Stability Report Spring 2021).