The international dimension of the ECB’s asset purchase programme

Speech by Benoît Cœuré, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Foreign Exchange Contact Group meeting, 11 July 2017

Large-scale asset purchase programmes have become an integral part of the set of unconventional tools central banks use to achieve their domestic objectives.[1]

When faced with negative output gaps and policy interest rates approaching their effective lower bound, these programmes have given central banks an essential tool to continue providing additional monetary accommodation, and prevent their domestic economies from falling into a deflationary trap.

Yet, in a world of integrated financial markets, purchase programmes do not only have domestic effects. This has been recognised by policymakers in the past. For example, there has been a lively debate about the effects of the Federal Reserve’s purchase programmes on financing conditions in emerging market economies.[2] However, less attention has been paid to this aspect in the case of the euro area – that is, the international spillovers of the ECB’s asset purchase programme (APP).

This is what I would like to discuss in my remarks today. Specifically, I plan to cover two topics. First, I will review what we know about the APP’s effect on net capital flows out of the euro area. And second, I will look at whether these capital flows have depressed exchange rates and, as a result, diverted demand away from other economies.

My main message is that the ECB’s APP does appear to have triggered substantial capital flows across borders. But it is far from clear whether this explains the depreciation in the effective exchange rate of the euro. In fact, asset purchases affect the exchange rate in broadly the same way as conventional monetary policy –through expectations of interest rate differentials.

Moreover, while unconventional monetary policies may drive down exchange rates, it does not make them a zero-sum game. The evidence suggests that the demand-boosting effects dominate – that is, the spillovers from our unconventional monetary policies have boosted growth and inflation prospects, not only in the euro area but also globally.

Post-APP international capital flows

Let’s start, then, by trying to get a sense of how strong international capital flows have been since we began our large-scale asset purchases. In other words, to what extent has there been a rebalancing towards foreign assets? Here some stylised facts from the euro area balance of payments data are instructive.

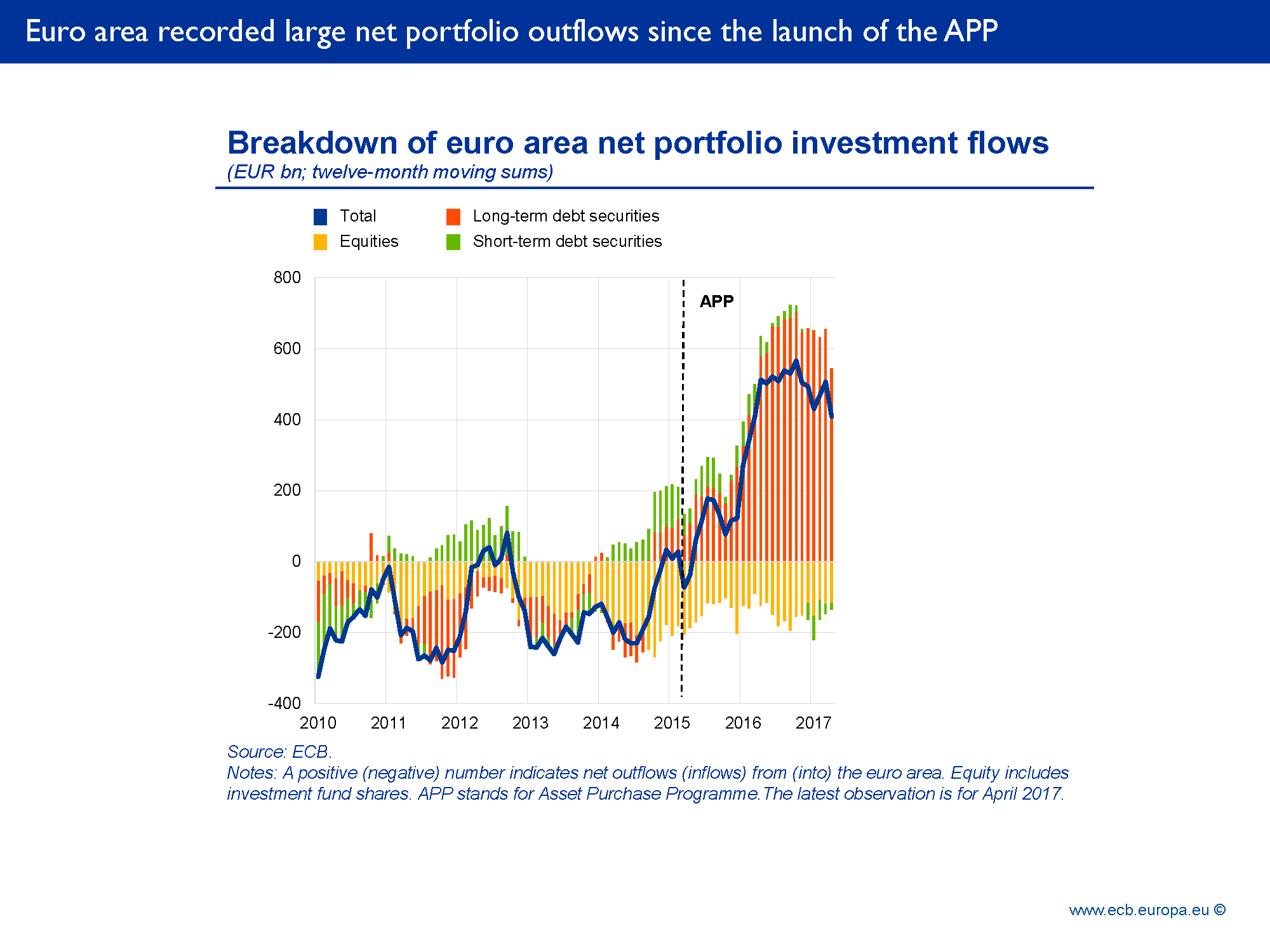

Slide 1

On slide 1 you can see that capital flows have indeed been considerable in the past few years. At their peak around the middle of 2016, net capital outflows – measured here in terms of 12-month moving sums – reached nearly 5% of euro area GDP. Never before in the history of the euro area have capital flows been so high.

Of course, in the absence of a counterfactual, we do not know how much of this is actually the result of our monetary policy measures. After all, investment decisions reflect a number of factors, including risk perceptions and, importantly, the yield that investors can earn abroad. Often, capital flows also simply reflect new investments and savings – just think about the euro area’s growing current account surplus – or they can be distorted by tax and regulatory arbitrage.

Yet, it is striking to see that the turnaround in capital flows from net inflows to net outflows started in mid-2014, just when we had announced our credit easing package and when expectations were gradually building among market participants that we would also begin purchasing government bonds.

Slide 1 also tells a second story – that among the various investment opportunities available to investors, virtually all net capital outflows have been concentrated in purchases of foreign long-term debt securities. Equity investment, by contrast, has hardly changed in net terms over time.

At face value, this suggests one tentative conclusion: large-scale purchases of sovereign bonds encouraged some investors to rebalance their portfolios towards the closest substitute – bonds issued by other sovereigns. This could be described as textbook quantitative easing (QE)[3], not least because these flows likely reflect the impact of our measures on bond prices in the euro area. According to ECB estimates, our monetary policy measures have contributed to reducing euro-area long-term risk-free rates by around 80 basis points since June 2014.[4] As a result, spreads over bonds issued by non-euro area sovereigns have increased notably.

For example, towards the end of last year the spread between ten-year US Treasuries and equivalent German Bunds hit levels above 200 basis points – its highest level since the fall of the Berlin Wall. On average last year, the spread was around 60 basis points higher than during the six months leading up to the launch of our credit easing package. And the observed spread already reflects the likely impact that increased purchases of foreign bonds has had on their prices. In other words, while our measures can be expected to have contributed to a widening of spreads, foreign rebalancing is likely to have caused the spreads to narrow. The net effect is what we see reflected in prices today.

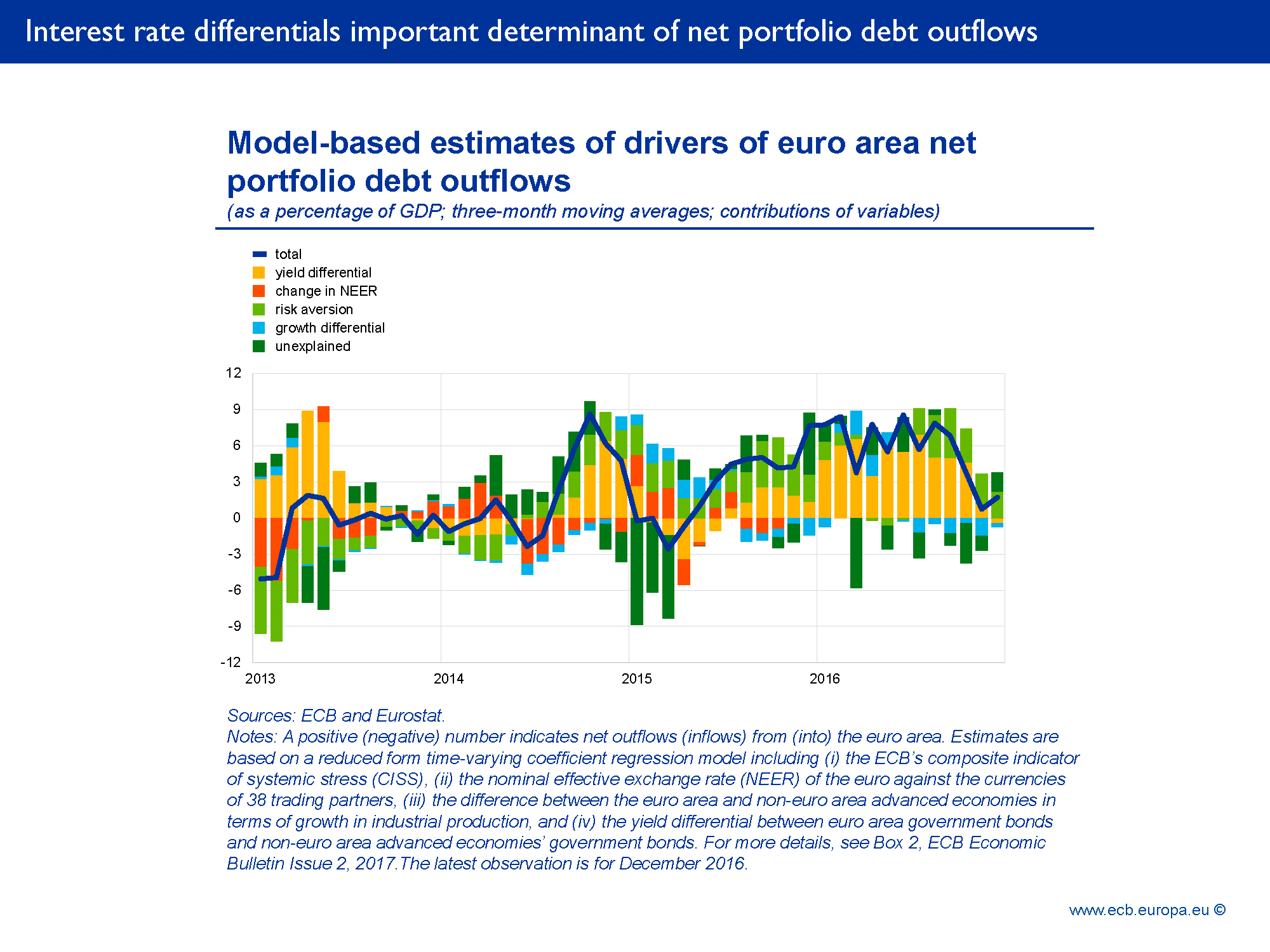

Slide 2

ECB internal model analysis confirms that yield spreads are an important driver of international portfolio flows.[5] On slide 2 you can see that yield differentials between euro area government bonds and those issued by non-euro area governments of advanced economies can explain a significant part of net debt outflows over the course of last year. Risk aversion can explain much of the remainder.

Now, net outflows in debt securities can mean two things: either euro area investors increasingly moved domestic funds abroad, or foreign investors – those resident outside the euro area – have sold euro area bonds. Both mechanisms are part of the type of portfolio rebalancing that policymakers typically have in mind when thinking about asset purchases. In practice, they can reinforce each other and this is what we have been seeing in the euro area.

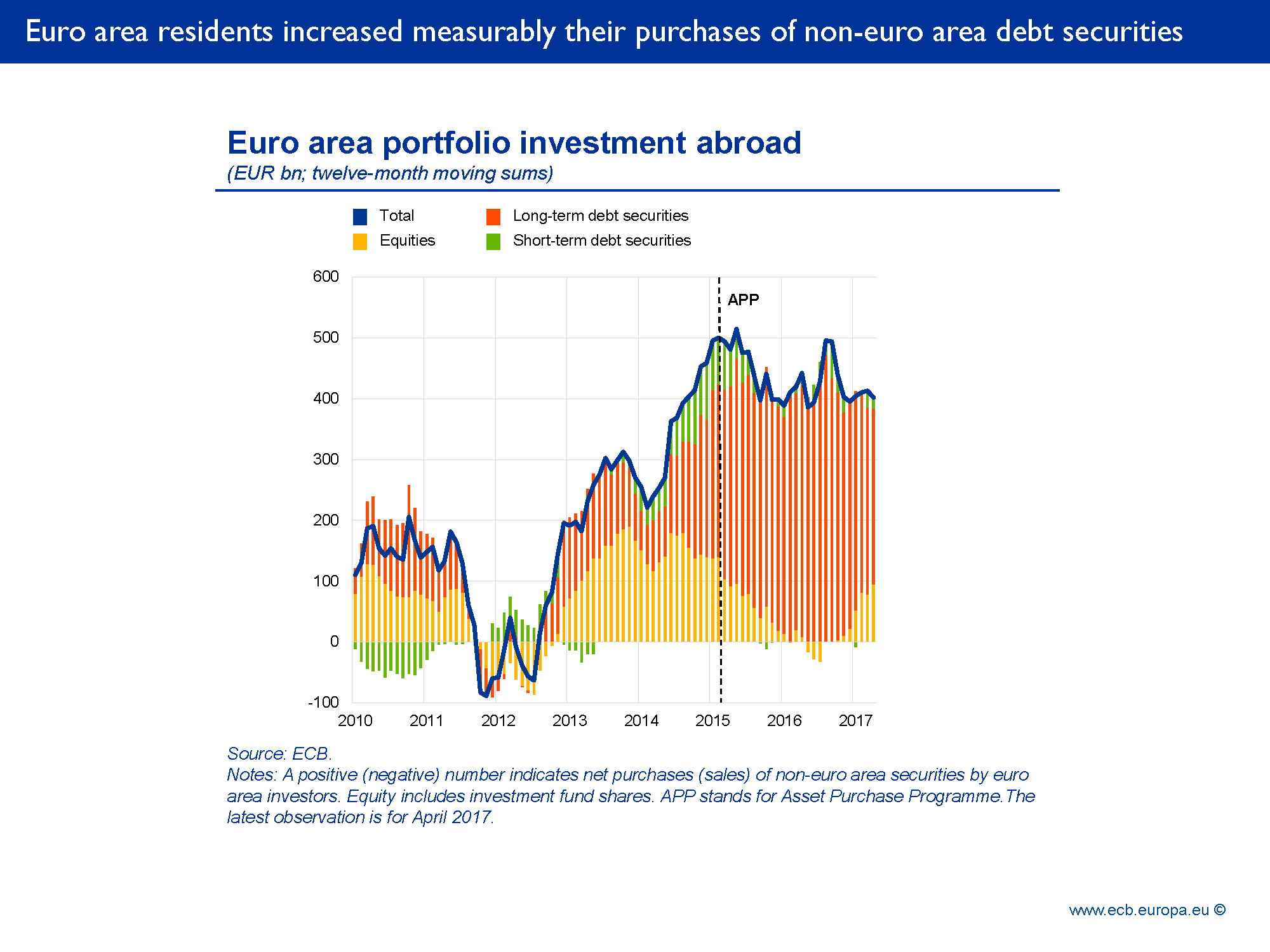

Slide 3

Consider slide 3. Here you can see that euro area investors have been a major driving force behind the net outflows. In fact, since the start of the APP in March 2015, net purchases by domestic investors have been almost entirely in the form of long-term foreign fixed income securities. There have been anticipation effects, but the chart strongly suggests that net debt outflows accelerated as the APP continued and decelerated only when we decided to reduce the pace of our monthly purchases in December last year.

Although it is unclear to what extent these flows ultimately influence bond prices, the pattern of international capital flows at least encourages discussion about the stock versus flow effects of central bank asset purchases – an interesting angle that should be explored further in future research.

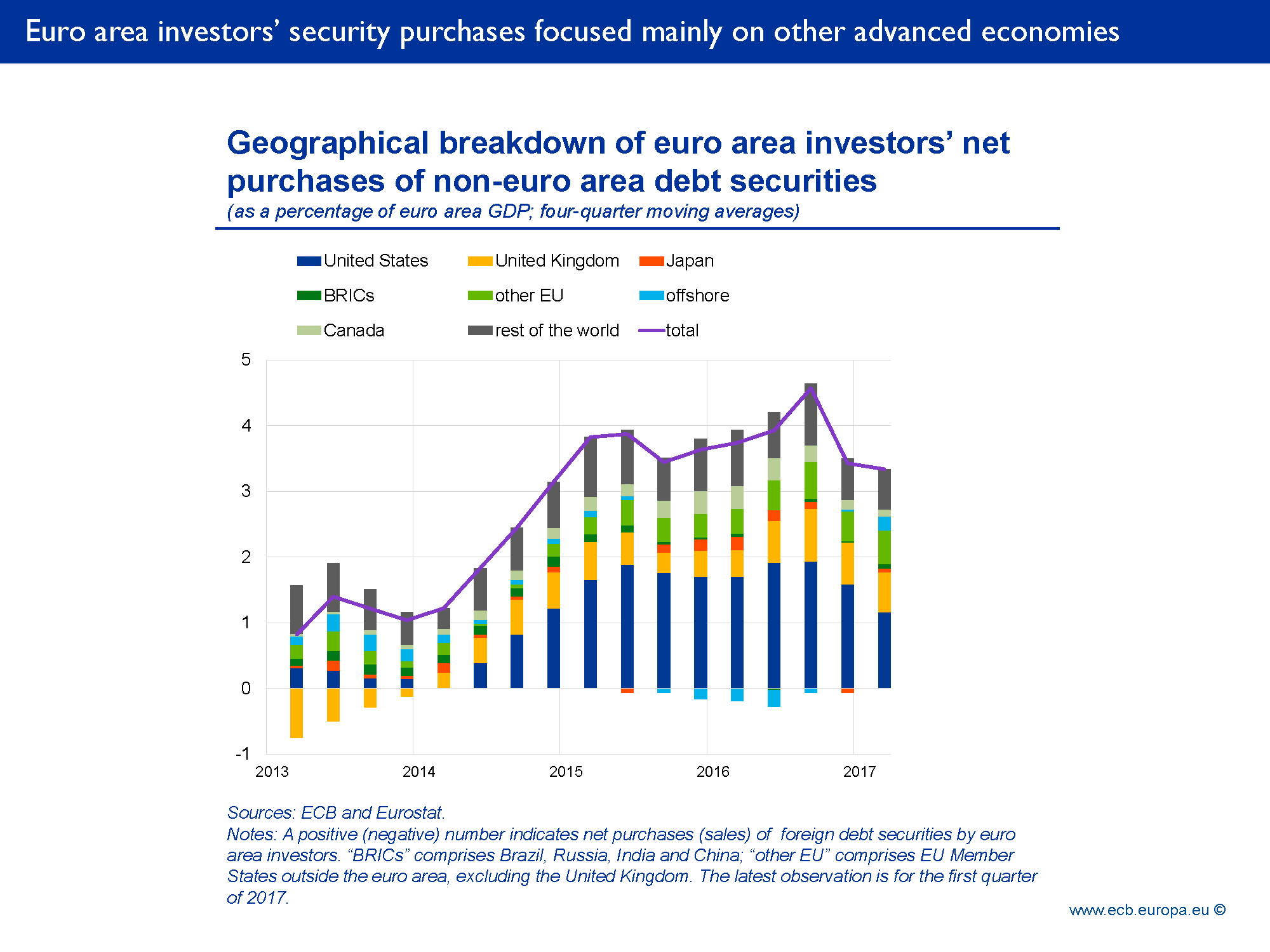

Slide 4

On slide 4 you can see that euro area investors did not only choose to rebalance into the closest substitute, namely government bonds, but also predominately into the safest of the issuers. Around two-thirds of net outflows went into securities issued by issuers in the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, Sweden and Canada. By contrast, and contrary to what has often been discussed in the wake of the Federal Reserve’s asset purchase programmes, there was hardly any investment into emerging market economies, including the BRICs – Brazil, Russia, India and China.

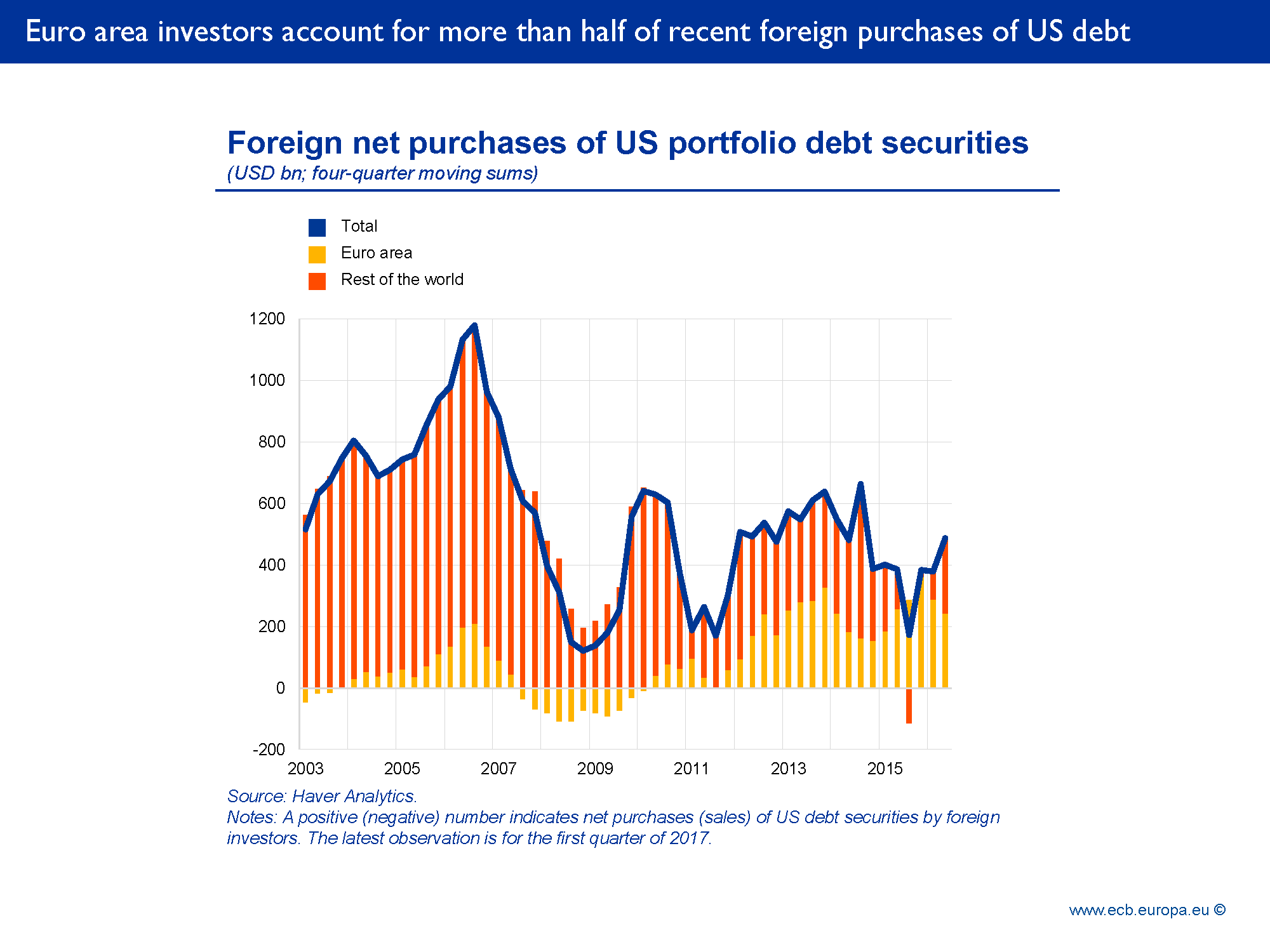

Slide 5

So euro area investors deliberately chose to redirect some of their funds into the closest substitute. Slide 5 shows the extent of this rebalancing more clearly. Since the start of the APP, euro area investors alone accounted for more than half of foreign purchases of US debt securities. History suggests that these shares are unusual for the euro area.

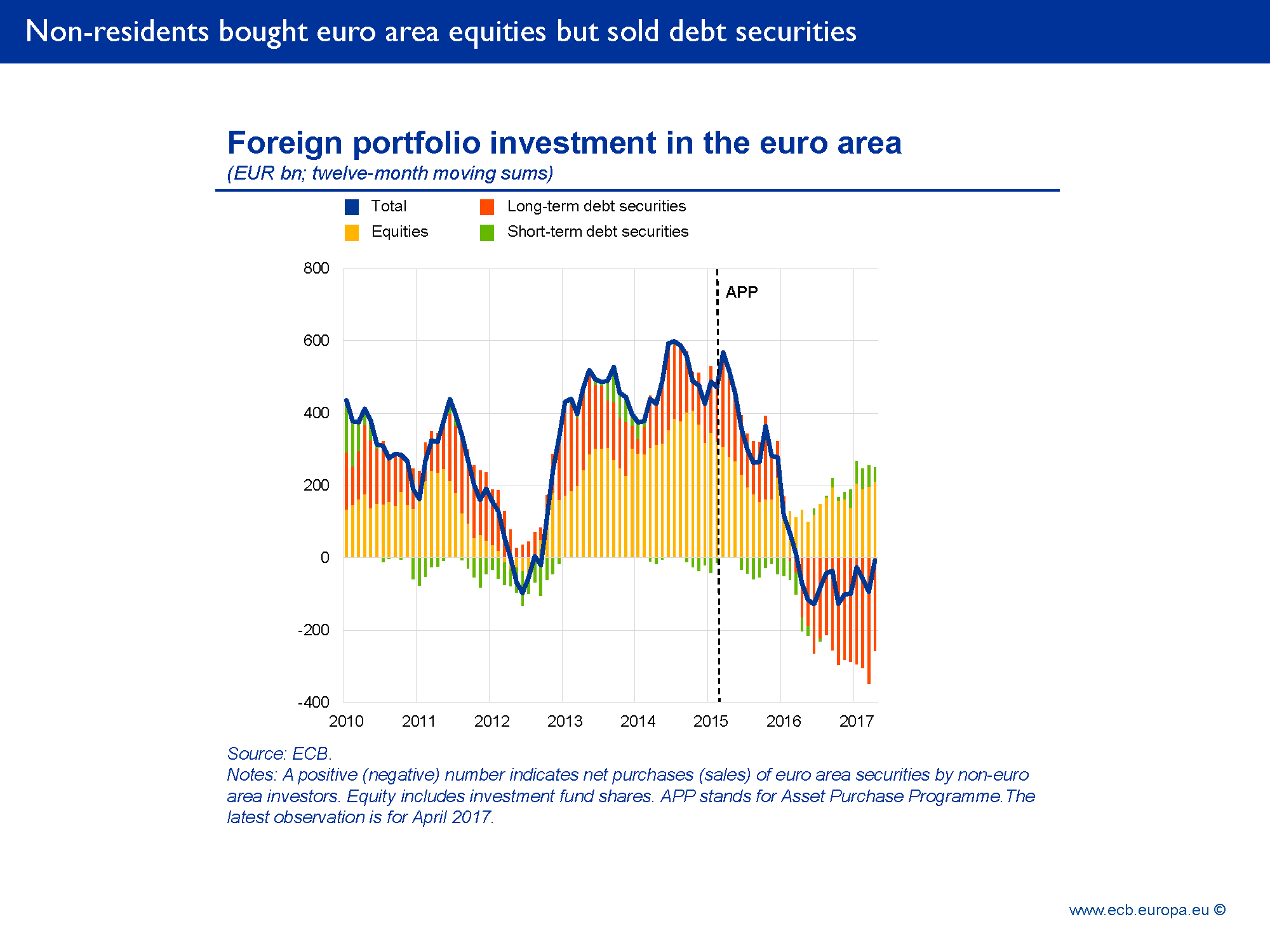

The other side of the coin is the behaviour of non-euro area investors. You can see this on slide 6. In net terms, foreign investors have been neither large sellers nor large buyers of euro area assets in recent months – the solid blue line is close to balance.

But this masks a significant difference between asset classes: foreign investors have been large buyers of euro area equity, while they were actively selling euro area bonds throughout most of last year, thereby reinforcing the actions of domestic investors.

Broadly speaking, this means two things: first, our policy measures have boosted confidence in the euro area’s growth prospects, which has brought foreign investors back to euro area stock markets. This confidence effect has also been confirmed in empirical studies.[6]

Slide 6

You can see clearly on slide 6 that this trend essentially started after the announcement of the outright monetary transaction (OMT) programme in mid-2012 and that inflows accelerated further in the aftermath of our credit easing package of June 2014. By the end of 2014, shortly before we announced purchases of government bonds, annual inflows into euro area stock markets by non-residents had reached 4% of euro area GDP – the highest on record. Policy stimulus and measures to repair the bank lending channel were clearly seen as having a positive effect overall on the euro area economy.

The second thing to note is that some selling of euro area bonds by non-residents is a mechanical feature of the ECB’s asset purchase programme. What I mean by that is that foreign investors are holding a relatively large share of outstanding euro area government bonds. For example, when we started the APP in March 2015, non-euro area investors were holding nearly 75% of German Bunds with maturities of seven to ten years. So it should not come as a surprise that around 45% of our purchases of government bonds have been with investors resident outside the euro area.[7] And if these foreign investors decide not to reinvest the proceeds from the sale in the euro area, a net outflow is recorded.[8]

This feature makes the ECB’s asset purchase programme structurally different from its counterpart in Japan, for example, where at the start of the Bank of Japan’s quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) in April 2013 less than 10% of outstanding Japanese government bonds (JGBs) were held by foreign investors. As a result, it is mainly domestic investors that have significantly reduced their JGB holdings in response to QQE.

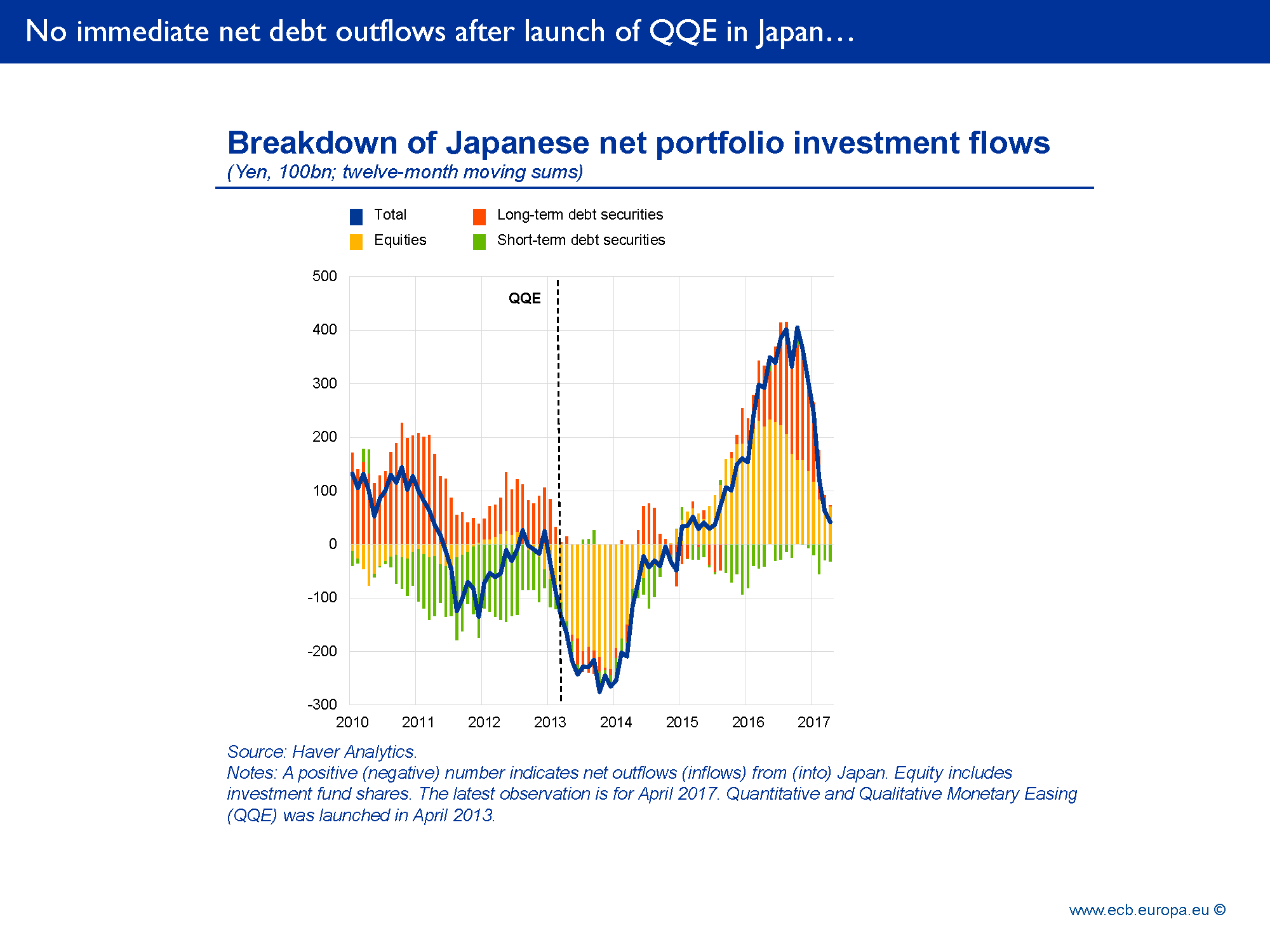

Slide 7

And as you can see on slide 7, they did not rebalance their portfolios towards foreign bonds: in the first two years after the start of QQE there were hardly any net outflows in debt securities despite a massive widening in international spreads following the US “taper tantrum” in mid-2013. Instead, QQE initially led to strong inflows into Japanese equities – a confidence effect similar to the one I have just described for the euro area. However, these inflows reversed relatively quickly.[9]

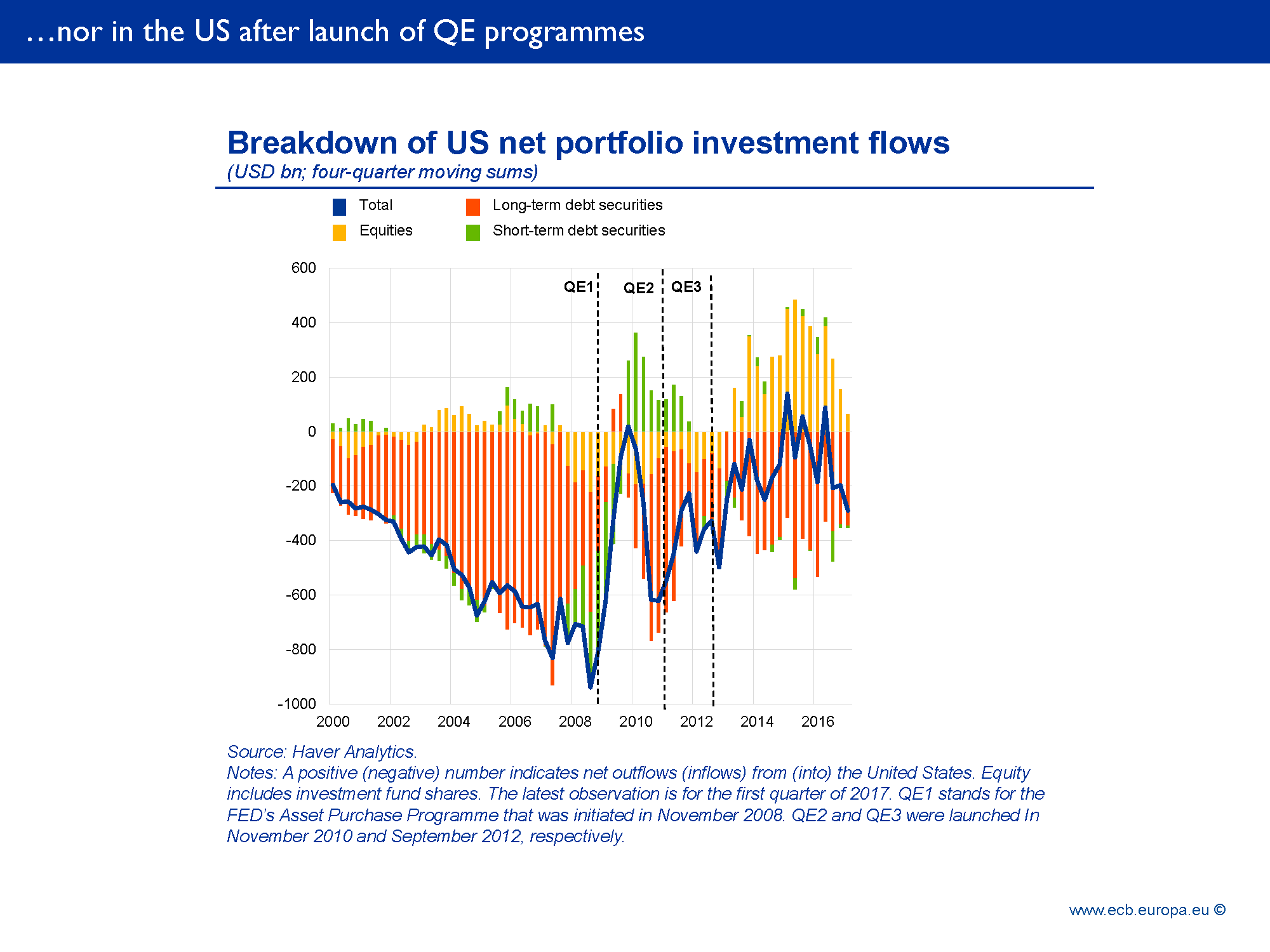

In the United States, by contrast, the holding structure of the Treasury market is more similar to that of the euro area bond market, but actual purchase patterns are notably different. Specifically, although non-residents owned around 60% of marketable US Treasuries in 2008, empirical evidence suggests that they were not the ones selling directly and indirectly to the Federal Reserve under its various rounds of QE.[10] You can see this on slide 8. In fact, perhaps with the exception of the first round (“QE-1”), foreign investors continued to pile into US Treasuries, in particular after the third round (“QE-3”).

Slide 8

This is not to say that quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve did not boost international capital flows. In fact, numerous studies, albeit mostly reliant on event studies over short periods of time, tend to suggest that it triggered sizeable flows into emerging markets, in particular after QE-2.[11] Yet, net portfolio flows, as you can see on slide 8, paint a broadly different picture of post-QE portfolio rebalancing than that seen in the euro area.

I see three main factors that can explain the difference in post-QE debt flows in the United States and the euro area.

First, the yield differential: ten-year US Treasuries and equivalent German Bunds were generating, on average, broadly the same return, in local currency, during the Fed’s QE programmes from late 2008 to early 2013. But, as I hinted at before, yield differentials were quite different in recent times. Since the start of the APP in March 2015, ten-year US Treasuries have been yielding, on average, around 170 basis points more than ten-year Bunds – an enormous difference that, to a large extent, reflects the divergence in monetary policy cycles that emerged in the wake of the euro area’s sovereign debt crisis. As a result, portfolio rebalancing during the ECB’s asset purchase programme has been more attractive for investors than it was during the Fed’s QE programmes.

The second factor is negative rates. In addition to yield differentials, the absolute yield level may also matter for investors, particularly if rates are negative. It may be no coincidence that net bond outflows were among the largest when ten-year German Bund yields hit a low of nearly -20 basis points last summer. In a recent survey among foreign central banks, 70% of the respondents reported that negative interest rates in the euro area had encouraged them to adjust their allocations to the euro.[12]

This emphasises the strong amplifier effect of negative rates – they are highly effective in boosting portfolio rebalancing effects, both domestically and across borders, exactly when monetary accommodation might be needed the most.

And third, we have political uncertainty and the role of the US dollar in the international financial system. The US dollar is the main reserve currency and US Treasuries are the world’s most important safe haven asset, and as such benefit from a liquidity advantage. Hence, in periods of elevated uncertainty, such as after Brexit, investors may overweight US Treasuries and underweight European assets. So, rebalancing out of US Treasuries is always likely to be more limited than out of any other safe security.

At this point I would like to draw three preliminary conclusions.

One is that unconventional policy measures can significantly boost confidence, leading foreign investors to review their international portfolio allocations, in particular with regard to equity.

A second conclusion is that the extent to which investors rebalance their portfolios towards foreign bonds is likely to depend on the structure of local bond markets, in particular the holding composition, and the risk-adjusted return investors can expect to receive from switching domestic and foreign bonds.

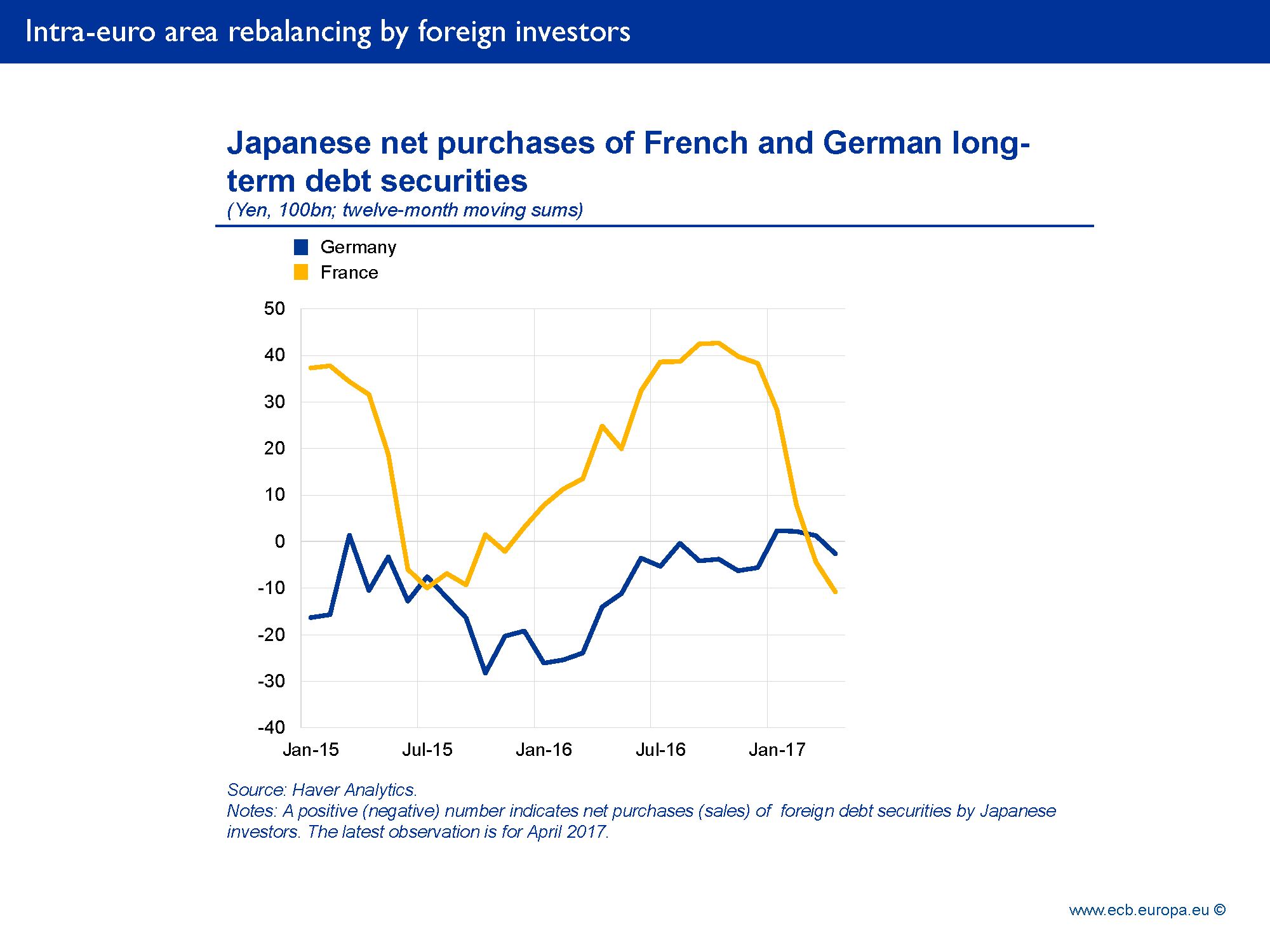

Slide 9

This means that there can also be noticeable differences between euro area countries, as can clearly be seen when looking at the recent behaviour of Japanese investors. Slide 9 shows that Japanese investors accumulated large positions in French securities in the aftermath of the launch of the APP, while at the same time selling German Bunds – a rebalancing within the currency union that likely reflected yield and safety considerations.[13]

And a third conclusion, more specific to the euro area, is that any future decline in the pace of our asset purchases is unlikely to have much direct negative impact on emerging markets, given that flows have been very limited.

Capital flows and exchange rates

So, the evidence is fairly clear that asset purchase programmes are associated with net capital flows, and probably also with changes in relative asset prices. This brings me to the second part of my remarks: the cross-border effect of asset purchases on exchange rates.

Two questions stand out. Do large-scale asset purchase programmes lead to exchange rate depreciation in the initiating country? And, if so, does monetary easing produce a beggar-thy-neighbour effect for other economies?

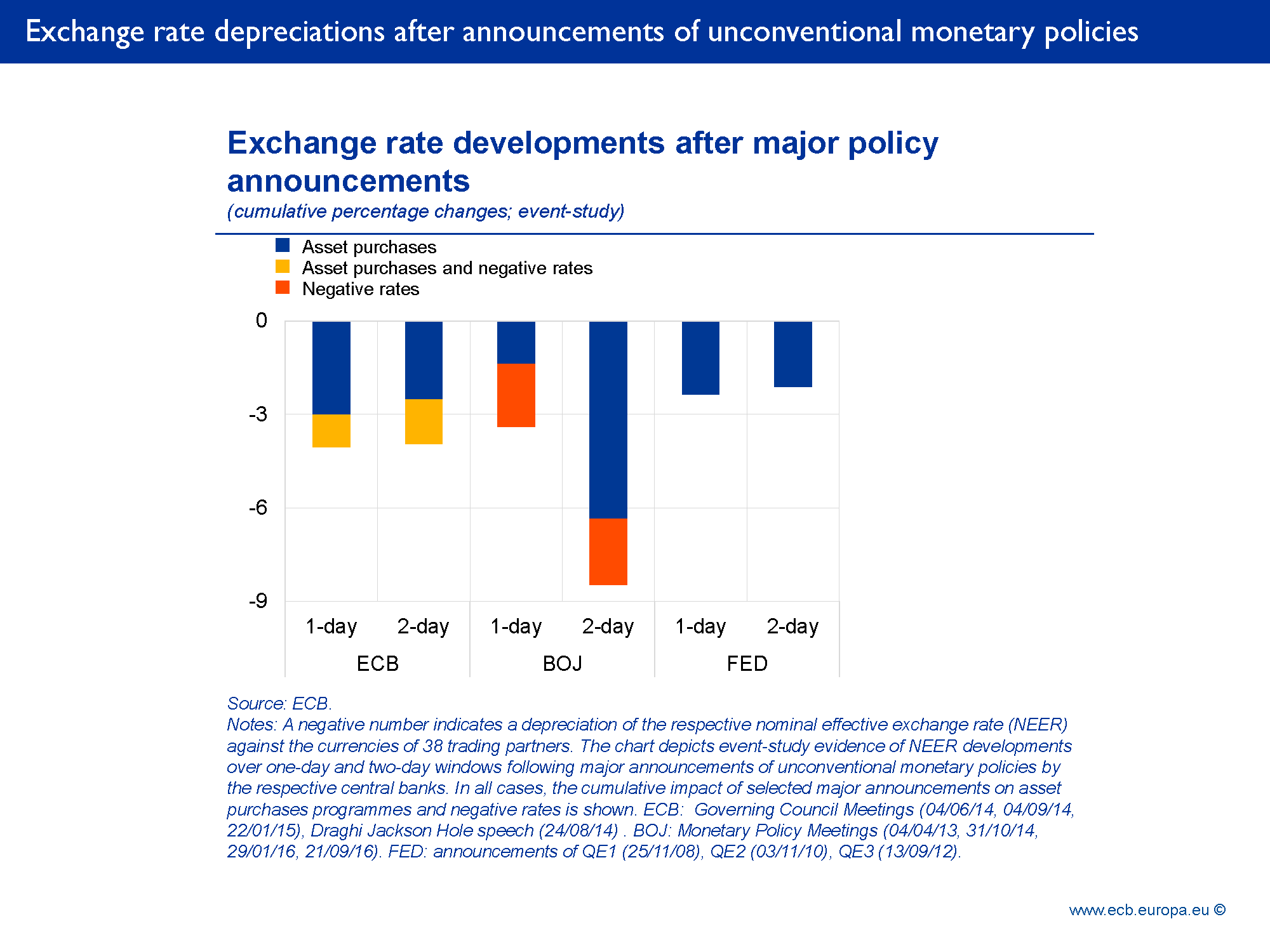

Slide 10

The first point to note is that, during announcements of asset purchase programmes, the currencies of all major central banks have indeed tended to depreciate. You can see this on slide 10, which shows, for all countries, the cumulative short-term impact of selected major announcements of asset purchase programmes and negative rates, or both.

Of course, exchange rates often change before actual announcements in anticipation of policy actions. In the case of the euro area, for example, studies of a larger number of events that include such prior signals and comments by policymakers find that the APP may have led to a depreciation of the euro of up to 12% against the US dollar.[14]

What is more, ECB in-house research suggests that negative rates not only amplify portfolio flows, they also amplify exchange rate movements. ECB staff estimate that the reduction in the deposit facility rate from 0% to -0.2% in the second half of 2014 led, cumulatively, to a 1.9% depreciation of the euro against the US dollar, of which 0.5 percentage points were due to the non-linear effects of interest rates moving into negative territory.

These non-linear effects could be related to the amplification of the carry trade channel, where currencies with negative funding costs may become the preferred short leg for carry trade strategies.[15] Negative rates can therefore amplify the initial volatility-supressing effect of asset purchases on carry trades. The lower the rates, the stronger these effects can be expected to be. This applies not only to the euro area but, as you can see on slide 10, also to Japan.

It is tempting to think that currency movements related to asset purchase programmes are a direct consequence of their impact on the supply of and demand for currency when investors rebalance their portfolios across borders. The truth, however, is that the direction of causality is much less clear in practice. Indeed, a recent Deutsche Bundesbank study finds that actual purchases under the APP have not led to statistically significant euro exchange rate movements.[16]

I see two main reasons for this.

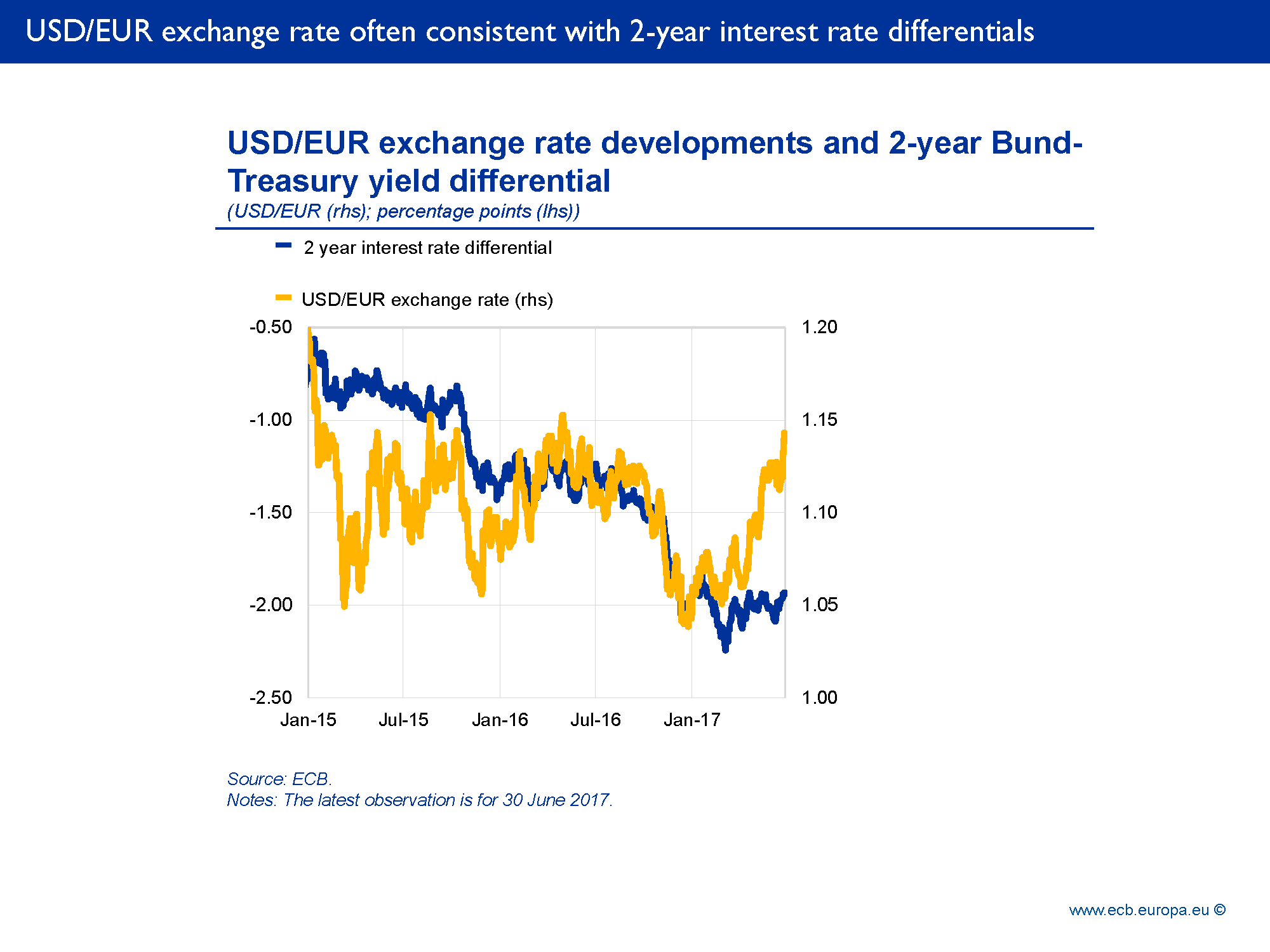

First, since exchange rates are asset prices that react in real time, they incorporate forward-looking expectations – most importantly expectations about short-term interest rate differentials. For instance, as you can see on slide 11, since the launch of the APP, the EUR/USD exchange rate has often closely mirrored two-year interest rate differentials between Germany and the United States.[17] Capital flows, by contrast, have tended to respond to interest rate differentials with a delay.

Slide 11

In other words, rather than driving exchange rate depreciation, capital flows typically take place after this depreciation has already happened. One reason for this delayed response may be that, during asset purchase announcements, asset managers achieve an immediate change in portfolio weights without active sales or purchases via “passive” rebalancing – that is, the change in the exchange rate and asset prices.[18]

This disconnect between the exchange rate and capital flows is consistent with the empirical finding that the exchange rate is mostly affected by the signalling channel of monetary policy – that is how policy decisions affect the expected future path of short-term interest rates. ECB research finds that the depreciation of the euro exchange rate in response to the APP announcement in January 2015 occurred mainly through this signalling channel, including the added credibility asset purchases provide to that expected path.[19] The portfolio rebalancing channel, by contrast, played much less of a role.[20] In this sense, the effect of asset purchases on exchange rates is not fundamentally different from conventional interest rate policy.

The second reason to be sceptical about capital flows affecting the exchange rate is linked more to the structure of foreign exchange markets. For example, a large share of euro foreign exchange transactions – 84% – is initiated outside the euro area, notably in the City of London.[21] As a result, they do not necessarily give rise to capital flows that affect the euro area. They are undertaken offshore.[22] The fact that foreign exchange trading in euro is so active in financial centres outside the euro area helps explain why there is often little correlation between cross-border capital flows and the euro’s exchange rate in the short to medium term.

In addition, portfolio outflows from the euro area – although large in size relative to economic activity – remain very small relative to overall transactions in euros in the foreign exchange market. They account at most for 0.2% of daily transactions in the euro-dollar pair, for instance.[23] And to the extent that such investments are hedged, the link between capital flows and exchange rate becomes even more tenuous.

Exchange rate spillovers and currency wars

Still, even if other effects of unconventional monetary policy, rather than capital flows, are the main influence on the euro exchange rate, the question of economic spillovers remains. This brings us to the “currency war” criticism of monetary policy.[24]

Those taking this line argue that currency depreciation caused by unconventional policy easing can divert domestic expenditure away from foreign imports, thus creating a zero-sum game.

Clearly such arguments need qualifying.

One way to do so is to use NiGEM, a well-known global macroeconomic model with an articulated external sector and international trade and financial linkages. Given the difficulties of capturing large-scale asset purchases in this model, policy easing at the lower bound is proxied by central banks imposing negative interest rates.

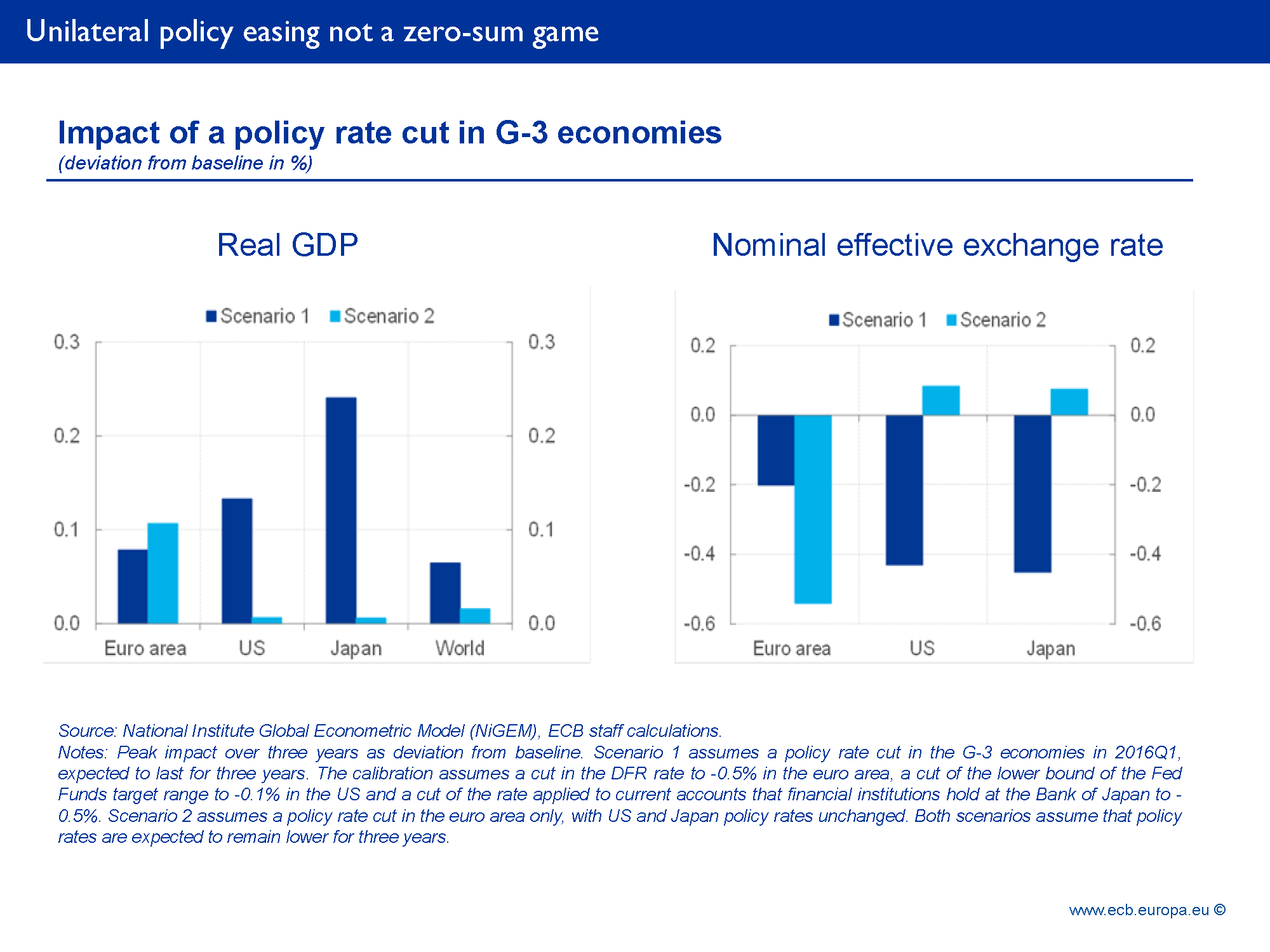

Slide 12

What you can see on slide 12 are two things. Scenario 1 portrays the impact of a multilateral, simultaneous cut in policy rates by the G-3 central banks, bringing rates into negative territory in all jurisdictions, including in the US. Scenario 2 involves a deepening of negative rates in the euro area only.

The scenarios illustrate two things.

First, the exchange rate channel is less important than most observers believe. Look at how similar the response of economic activity in the euro area is under the two scenarios, even though the exchange rate depreciation is less than half under the multilateral case. Clearly, the expansionary effect of monetary policy easing is the dominant factor – in practice probably even more so as evidence is growing that the exchange rate pass-through to final consumer prices has steadily fallen in recent years.[25]

Second, unilateral policy actions are not a zero-sum game. Scenario 2 demonstrates that, although the currencies of our trading partners appreciate, a unilateral cut in the euro area interest rate is a net positive for all countries individually, and for the global economy as a whole. That is, if unconventional monetary policy helps prevent a country stuck at the lower bound from being a drag on global demand, all countries can benefit. This has also been well documented in the academic literature.[26]

In the case of the euro area, the demand-augmenting effects are clearly visible. For example, since we introduced our credit easing package in mid-2014, net exports have hardly contributed to GDP growth. The recovery has been driven almost entirely by domestic demand, supported by a virtuous circle between rising employment, labour income and consumption.

Certainly, if we abstract for a moment from the fact that mark-up adjustments could have taken place, the fall in the euro exchange rate may have helped exporters hold onto their market shares as world trade stalled. But by far the most dominant effect of our monetary policy has been to encourage these domestic growth forces.

In other words, far from “beggaring its neighbours”, monetary policy easing by the ECB has added to global demand and thereby stabilised the global economy, in particular after the euro area had been a major drag on global growth for many years. In the last three years the euro area’s share of global growth has become much more significant, contributing 0.5 percentage points, on average, to the 1.9% growth in advanced economies.

Moreover, we also responded to a number of significant common, global shocks, such as the protracted period of low oil prices and the slowdown in growth in emerging market economies, which threatened not only the achievement of our price stability objective, but also that of many other central banks. So, the combined effects of stabilising the euro area economy – a significant source of demand for many countries – and cushioning global shocks contributed to putting global growth back on it current path.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Asset purchase programmes have been instrumental in easing monetary policy at the effective lower bound in major advanced economies. A wealth of evidence suggests that these policies have successfully boosted economic growth and inflation prospects. At the same time, they have clearly had spillover effects on other countries via capital flows and relative asset price movements.

The evidence does not suggest, however, that these capital flows have led to major exchange rate movements. Rather, exchange rates have responded to forward-looking interest rate differentials. Asset purchase programmes, together with negative interest rates, may have exacerbated those differentials through signalling and non-linear effects, but their effect on exchange rates is, by and large, not fundamentally different from conventional policy.

What is more, currency depreciation is a side-effect of policy and neither its main transmission channel, nor its objective. Monetary policy actions aimed at supporting domestic price stability objectives in advanced economies have been clearly positive for the global economy, mainly by stimulating employment, incomes and, ultimately, economic growth.

This is particularly the case in the euro area, which, thanks to a rich set of carefully calibrated monetary policy measures, is now adding to, rather than subtracting from, global growth. In this sense, the view that asset purchase programmes in large advanced economies have encouraged harmful currency wars is misleading. The world of monetary policy is not an arena where central banks engage and compete for advantage.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] I would like to thank Roland Beck, Arnaud Mehl and Martin Schmitz for their contributions to this speech. I remain solely responsible for the opinions contained herein.

[2] See, for example, Rajan, R. (2014), “Competitive monetary easing: is it yesterday once more?”, remarks at the Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, April 10; and Bernanke, B. S. (2015), “Federal Reserve Policy in an International Context”, paper presented at the 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference hosted by the International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, 5 and 6 November.

[3] For a discussion of the transmission channels of QE, see e.g. Cœuré, B. (2015), “Embarking on public sector asset purchases”, speech at the Second International Conference on Sovereign Bond Markets, Frankfurt, 10 March.

[4] See e.g. ECB (2017), “Impact of the ECB’s non-standard measures on financing conditions: taking stock of recent evidence”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

[5] See ECB (2017), “Analysing euro area net portfolio investment outflows”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2.

[6] See Fratzscher, M., et al. (2014), “ECB unconventional monetary policy actions: market impact, international spillovers and transmission channels”, paper presented at the 15th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference; and Georgiadis, G., and Gräb, J. (2016), “Global financial market impact of the announcement of the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, Journal of Financial Stability, 26, pp. 257-265.

[7] See ECB (2017), “Which sectors sold the government securities purchased by the Eurosystem?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4.

[8] Slide 6 also shows that there have been net inflows by non-residents into short-term debt securities, which likely reflects the temporary placement of excess liquidity of foreign investors with no access to the ECB’s deposit facility. See Cœuré, B. (2017), “Bond scarcity and the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech at the Club de Gestion Financière d’Associés en Finance, Paris, 3 April.

[9] The reversal was probably reinforced by the Japanese government’s decision, in April 2015, to increase the Government Pension Fund’s investment in foreign equities (the Government Pension Fund is the largest of its kind in the world).

[10] See Carpenter, S., Demiralp, S., Ihrig, J., and Klee, E. (2015), “Analyzing Federal Reserve asset purchases: From whom does the Fed buy?,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 52, pp. 230-244.

[11] See, for example, Neely, C. (2010), “The Large-Scale Asset Purchases Had Large International Effects”, Working Paper Series, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Fratzscher, M., Lo Duca, M. and Straub, R. (2013), “On the International Spillovers of US Quantitative Easing,” Discussion Papers, DIW Berlin; Moore, J. et al. (2013), “Estimating the Impacts of U.S. LSAPs on Emerging Market Economies’ Local Currency Bond Markets”, Staff Reports, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, No 595; Rogers, J. H., Scotti, C. and Wright, J. H. (2014), “Evaluating Asset-Market Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy: A Cross-Country Comparison”, International Finance Discussion Papers, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, No 1101.

[12] See also ECB (2017), The International Role of the Euro, July. The share of the euro in global foreign exchange reserves actually increased in 2016, even after controlling for valuation effects arising from exchange rate movements. This suggests that adjustments in the holdings in question were limited or concerned official reserve holders with small holdings.

[13] The sharp decline in flows to France towards the end of 2016 and early 2017 likely reflected political concerns.

[14] See Altavilla, C., Carboni, G. and Motto, R. (2015), “Asset purchase programmes and financial markets: lessons from the euro area”, ECB Working Paper No. 1864.

[15] This is consistent with net short positioning against the euro between May 2014 and May 2017 in weekly data on commitments of traders collected by the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

[16] See Deutsche Bundesbank (2017), “The Eurosystem’s bond purchases and the exchange rate of the euro”, Monthly Report, January.

[17] The recent decoupling suggests that factors other than relative monetary policy expectations are likely to have contributed to a stronger euro in recent months, such as changes in risk premia. Market observers have pointed, for instance, to signs of unwinding of what they called the “reflation trade” in US financial assets, and to improved sentiment towards the euro area in the wake of the French presidential elections.

[18] See Bubeck, J., Habib, M., and Manganelli, S. (2017), “The portfolio of euro area fund investors and ECB monetary policy announcements”, mimeo, ECB, presented at the joint ECB-BoE-IMF workshop on “Spillovers from macroeconomic policies”, Washington D.C., 26 April.

[19] See Andrade, P., Breckenfelder, J., De Fiore, F., Karadi, P. and Tristani, O. (2016), “The ECB's asset purchase programme: an early assessment”, ECB Working Paper No. 1956, and the literature quoted in there.

[20] See Georgiadis and Gräb, op cit.

[21] This refers to the location of the initiating sales desk, which may not coincide with the location of the trading desk. See ECB (2017), The international role of the euro, July.

[22] And, sometimes, even in co-locations where high-frequency trading firms’ computers are in the same data centres as exchange servers.

[23] Based on euro area portfolio investment abroad, measured in terms of 12-month moving sums, which peaked in early 2015, suggesting a level of €2 billion per day (assuming that there are 250 business days). This compares with $1.2 trillion worth of daily transactions in the euro-dollar pair, according to the BIS Triennial Survey of April 2016.

[24] For an earlier discussion, see Cœuré, B. (2013), “Currency fluctuations: the limits to benign neglect”, speech at the luncheon panel: Currency Wars and the G-20’s Goal of Strong, Sustainable, and Balanced Growth, Conference on Currency Wars: Economic Realities, Institutional Responses, and the G-20 Agenda, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, D.C., 2 April.

[25] See e.g. ECB (2016), “Exchange rate pass-through into euro area inflation”, Economic Bulletin, July.

[26] See also Caballero R., Fahri, E. and Gourinchas, P. O. (2015), “Global Imbalances and Currency Wars at the ZLB”, NBER Working Paper No. 21670, The National Bureau of Economic Research, who show that in a global liquidity trap expansionary monetary policy around the zero lower bound in one country alleviates the global asset shortage and stimulates the economy in all countries, thereby being a positive-sum remedy in contrast with zero-sum exchange rate devaluations.

Európska centrálna banka

Generálne riaditeľstvo pre komunikáciu

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt nad Mohanom, Nemecko

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Šírenie je dovolené len s uvedením zdroja.

Kontakty pre médiá