The performance and resilience of green finance instruments: ESG funds and green bonds

Published as part of the Financial Stability Review, November 2020.

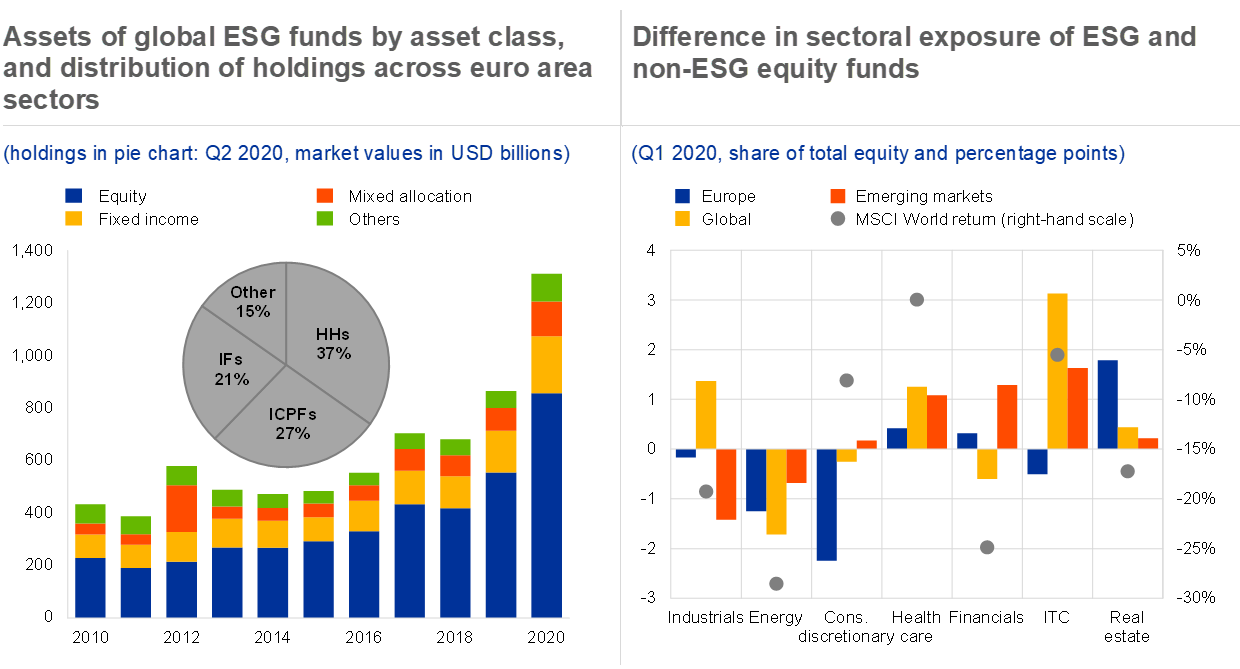

Green financial markets are growing rapidly globally. Assets of funds with an environmental, social and governance (ESG) mandate have grown by 170% since 2015 (see Chart A, left panel). The outstanding amount of euro area green bonds has increased sevenfold over the same period. Given the financial stability risks stemming from climate change,[2] this box aims to understand the performance of such products and their potential for greening the economy. It focuses on the resilience of ESG funds and the absence of a consistent “greenium” a lower yield for green bonds compared with conventional bonds with a similar risk profile reflecting the fact that green projects do not benefit from cheaper financing.

Chart A

ESG funds have grown rapidly and tend to invest in sectors less affected by the recent market turmoil

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Refinitiv, ECB securities holdings statistics by sector and ECB calculations.

Notes: The bars in the left panel show the assets of funds listed as ESG funds by Bloomberg, while the pie chart is based on a sample of 1,076 ESG funds domiciled in the euro area, comprising 554 equity funds, 262 bond funds and 216 mixed funds. Mixed funds are classified as equity or bond funds if the respective share of equity or bond investments exceeds 50%. HHs: households; ICPFs: insurance corporations and pension funds; IFs: investment funds. The right panel is based on the same 1,076 ESG funds and 23,699 non-ESG funds domiciled in the euro area, split according to the geographical focus of their holdings. For each fund type, the average investments in each sector by ESG and non-ESG funds are compared (>0: ESG funds invest more). Values are in percentage points. The dots represent the sectoral return based on the MSCI World Industrials Index between February and April 2020. ITC: information technology and communication services.

Euro area investors have pivoted towards ESG funds since the onset of the coronavirus. The aggregate exposure of euro area sectors to ESG funds has increased by 20% over the last year. Households and ICPFs hold over 60% of euro area ESG funds (see Chart A, left panel). In the first quarter of 2020, euro area financial institutions and households reduced their non-ESG fund holdings (down by 1-8%, depending on the holder sector) in favour of ESG funds (up by 4-10%). The implied higher resilience of ESG fund flows during the market turmoil could reflect a more stable and committed investor base,[3] as well as a lower exposure to underperforming sectors such as energy (see Chart A, right panel). However, although an EU Ecolabel for retail financial products is under discussion at the European Commission, there is currently no regulatory definition of ESG funds, creating the potential for so-called “greenwashing”.[4]

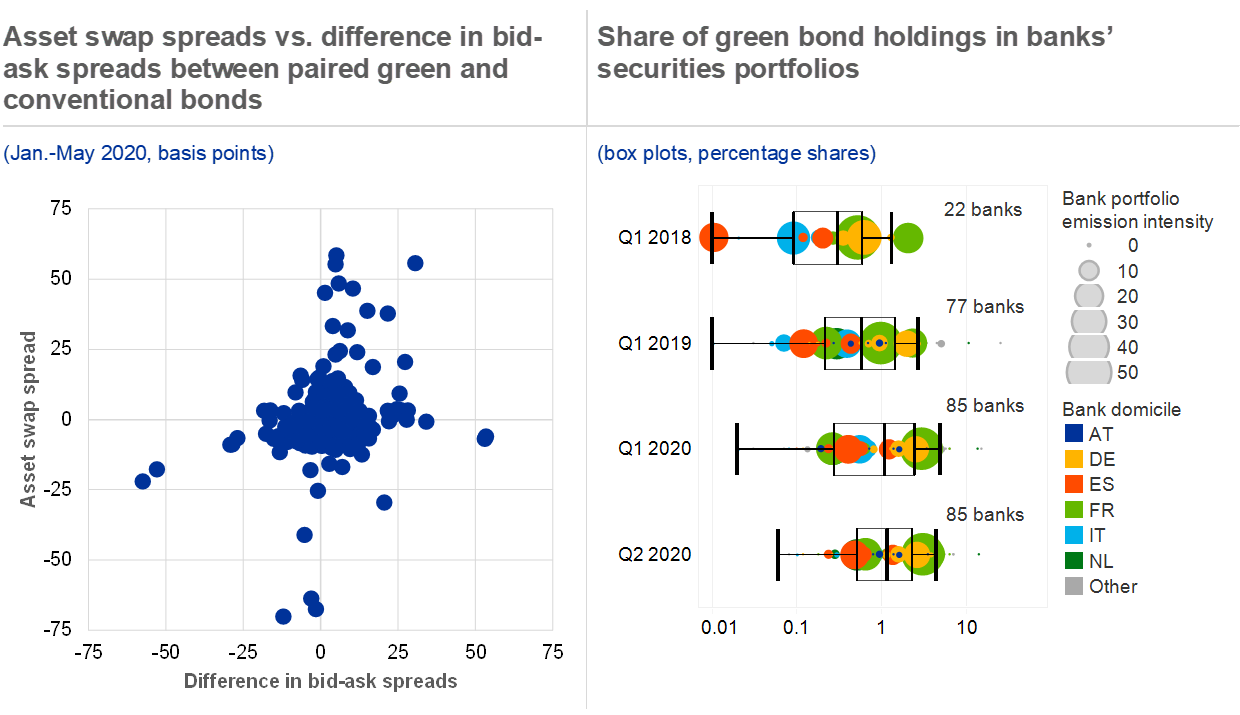

In parallel, almost all sectors also increased their holdings of green bonds in the first quarter of 2020. Euro area investors now hold €197 billion of euro area green bonds. Market intelligence suggests that green bonds were issued in primary markets at lower interest rates and with larger order books than conventional bonds in 2019 and 2020. In the secondary market, however, green bonds do not consistently differ from similar conventional bonds either in terms of interest rates or liquidity (see Chart B, left panel). The finding that green bonds do not provide cheaper funding may reflect the fact that investors do not fully price in climate-related risks and/or that green bonds carry a risk of “greenwashing” in the absence of clear standards.[5] Indeed, while green bonds target green projects, evidence that the bonds lead to lower carbon emissions by issuers is limited.[6] Moreover, issuers are not accountable for the targets of projects financed by green bonds not being reached, although the standardisation of verification and reporting of green bonds is now under discussion at the European Commission as a part of the EU Green Bond Standard.

Chart B

No consistent premium for green bonds, while banks keep increasing their green assets

Sources: Dealogic, Refinitiv, Bloomberg Finance L.P., IHS Markit, ECB securities holdings statistics by sector and ECB calculations.

Notes: Left panel: the greenium and difference in bid-ask spreads are calculated as the spread between the respective values for green and conventional bonds of the same issuer, the same maturity, the same currency, and a similar size and coupon. Daily spreads are averaged over three periods: 1 January-20 February 2020 (before COVID-19 turmoil), 20 February-18 March 2020 (COVID-19 turmoil), 18 March-31 May 2020 (after the launch of the pandemic emergency purchase programme). A negative spread indicates a greenium. Right panel: bank portfolio emission intensity is the volume-weighted CO2 emission intensity of banks’ non-financial corporate loan portfolio; it is given by the size of the bubble. Emission intensity is measured in tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions produced by a non-financial firm per million euro of sales. The black vertical lines indicate the interquartile range and the median for the green holdings of the banks in the sample. The number of banks indicates how many banks had invested in green bonds.

As green markets have developed, euro area banks have also increased their role in green financing. Euro area banks have increased the share of green bonds in their portfolios, although the median share of green investments is still only just above 1% of total bank securities holdings (see Chart B, right panel). However, banks are also increasing their own issuance of green bonds, in some cases to provide green financing opportunities to firms that are traditionally loan-financed. In the third quarter of 2020, new green bond issuance accounted for 13% of total euro area bank bond issuance, up from just 4% in the first quarter of 2020, following the rapid expansion of the green bond market in the second half of the year.

Financial markets can help to support the transition to a more sustainable economy and reduce vulnerability to climate-related risks. Although possible market failures can stem from incomplete, inconsistent and insufficient disclosure of environmental data, the increase in bond issuance in response to the pandemic provides an opportunity to deepen the green financial market.[7] And the continuing shift towards ESG funds can also help to foster the green transition, especially given the potentially important role of equity markets in financing green projects.[8] The resilience of green finance instruments during the recent market turmoil suggests that investors do not need to make sacrifices on performance to help foster the transition to a greener economy.

- Sante Carbone, Angelica Ghiselli and Filip Nikolic provided data support.

- See Special Feature A entitled “Climate change and financial stability”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May 2019. For a discussion on the vulnerability of financial markets to tail events stemming from the mispricing of climate risks, see Schnabel, I., “When markets fail – the need for collective action in tackling climate change”, speech at the European Sustainable Finance Summit, 28 September 2020.

- See Riedl, A. and Smeets, P., “Why Do Investors Hold Socially Responsible Mutual Funds?”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 72, Issue 6, 2017, pp. 2505-2550, and Hartzmark, S. and Sussman, A., “Do Investors Value Sustainability? A Natural Experiment Examining Ranking and Fund Flows”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 74, Issue 6, 2019, pp. 2789-2837.

- The European Commission is developing the EU Ecolabel for Retail Financial Products within the framework of the Sustainable Finance Action Plan.

- See Schnabel, I., “When markets fail – the need for collective action in tackling climate change”, speech at the European Sustainable Finance Summit, 28 September 2020.

- See Ehlers, T., Mojon, B. and Packer, F., “Green bonds and carbon emissions: exploring the case for a rating system at the firm level”, BIS Quarterly Review, Bank for International Settlements, September 2020.

- See “Positively green: Measuring climate change risks to financial stability”, European Systemic Risk Board, June 2020, and Schnabel, I., “Never waste a crisis: COVID-19, climate change and monetary policy”, speech at the roundtable on “Sustainable Crisis Responses in Europe” organised by the INSPIRE research network, 17 July 2020.

- See De Haas, R. and Popov, A., “Finance and carbon emissions”, Working Paper Series, No 2318, ECB, September 2019, and “Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area”, ECB, March 2020.