Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 3/2022.

1 Introduction

In most advanced economies, income and wealth inequality have increased since the early 1980s, although the available data point to diverse national trajectories. Wealth concentration and income inequality have been shown to be rising in continental Europe, but substantially less so than, for example, in the United States and the United Kingdom.[1] The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is likely to further amplify economic inequalities. Income inequality could increase as a result of higher unemployment and loss of income among younger workers, women, those in lower income and lower education groups and temporary workers.[2] Moreover, rising asset prices, such as those of stocks and real estate, together with changes in consumption and savings behaviour across different parts of the wealth distribution during the pandemic, may contribute to greater wealth inequality.[3]

Citizens have expressed concerns about economic inequalities in the context of the ECB’s Strategy Review.[4] Empirically, studies have shown that monetary policy may only have a limited impact on economic inequalities and that, overall, the easing of monetary policy appears to have somewhat dampened economic inequality in the euro area in recent years.[5] At the same time, it has been shown that inequality could play a role in the transmission of monetary policy, highlighting the need to improve understanding of the ways in which inequality can have an impact on the fulfilment of the ECB’s mandate.

One aspect that has received less attention is how a perceived increase in inequality could affect public trust in central banks, and how this could affect the fulfilment of central banks’ mandates. In the European context, rising economic inequalities have been found to depress public trust in the EU and its institutions, both directly and indirectly through the negative impact of inequality on trust in national institutions.[6] This may have an impact on the ECB, as public trust is of relevance both for the anchoring of inflation expectations, which increases the effectiveness of monetary policy,[7] and to shield it from political pressures that could undermine its independence.

This article explores the relationship between economic inequalities and public trust in the ECB and other European institutions. Drawing on data from the ECB’s new Consumer Expectations Survey and the Standard Eurobarometer, it analyses the relationship between different forms of economic inequality, perceptions of inequality and public trust in the ECB and other EU institutions in the euro area over the period 1999-2020 and in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Section 2 discusses the relevance of economic inequality for institutional trust in general and for trust in the ECB in particular. Section 3 examines different dimensions and measurements of economic inequality and their evolution in the euro area. Section 4 then analyses the relationship between different measures of economic inequality and public trust in the ECB and other EU institutions, such as the European Commission and the European Parliament. Section 5 concludes.

2 The relevance of economic inequality for institutional trust

Greater economic inequality tends to reduce trust in public institutions. Economic inequality can be understood as a normative standard and a substantive policy outcome by which citizens evaluate government performance. When institutions fail to provide sufficient resources for all citizens or fail to ensure a relatively even distribution of resources, leading to economic inequality, poverty and economic exclusion, the expectations of some citizens are not met, depressing trust in institutions. Empirically, higher levels of income and wealth inequality have been found to correlate with lower levels of trust in political institutions and weakened support for democracy in general.[8]

Contextual factors can moderate the relationship between economic inequality and institutional trust. Country-specific norms, past performance of one’s own country and the example of other countries all provide benchmarks for citizens to evaluate levels of inequality in their own society.[9] Concerns about inequality also seem to have a stronger effect on trust in times of crisis, when issues of economic exclusion and decline are more salient.[10] However, the effect of inequality on trust appears to be weaker in the presence of strong welfare policies and strong redistributive policies, highlighting the role of public policy in mitigating the political consequences of inequality.[11]

The impact of economic inequality on institutional trust is also mediated by individual perceptions, beliefs and experiences. Research shows that perceptions of inequality do not always coincide with statistically measured levels of wealth and income disparity.[12] Moreover, citizens hold different normative beliefs about the desirable distribution of wealth and income in society, and this may influence institutional trust.[13],[14] Finally, the relationship between macro-level inequality and individuals’ trust in public institutions also depends on the socioeconomic background of people and their position in the income and wealth distribution.[15]

Perceptions of the performance of political institutions in addressing inequality also seem to be relevant for central banks. Recent evidence suggests that concerns of citizens about inequality are directed not only at governments – the actor with the primary responsibility for the issue and the capacity to address it – but also at central banks. During the ECB’s listening events in the context of the monetary policy strategy review, citizens argued that the ECB should assume a more prominent role in addressing societal issues, like inequality and poverty.[16] This suggests that citizens expect their central banks to take action. When these expectations are not met, public trust in the central bank may be negatively affected through the mechanisms described in the paragraphs above.

The literature on the impact of economic inequality on public trust in central banks is limited. Few empirical analyses have explored links between perceptions of economic inequality and trust in central banks such as the ECB. It has been observed that trust in the ECB is related to views on the effects of monetary policy measures on inequality.[17] Moreover, levels of income inequality seem to be associated with public trust in the ECB, especially in times of crisis.[18] Finally, it may not only be statistically measured levels of inequality that matter, but also subjectively perceived levels. A study focusing on the Bank of England found that people who are happy with the current income distribution are more likely to trust the central bank.[19]

3 Dimensions and perceptions of economic inequality

Different measures of economic inequality cover different aspects of inequality and draw on different methods for determining economic well-being and its distribution in society. It is important to understand these methodological differences, as these may affect findings concerning the empirical relationship between trust and inequality. In particular, it is important to differentiate between objectively measured levels of inequality and subjective perceptions of inequality.

Among the dimensions of inequality, the most common distinction is between income and wealth. While both income and wealth inequality have risen in most advanced economies since the early 1980s, the concentration of wealth tends to be greater than the concentration of income.[20] Income inequality can be measured on the basis of either pre-tax or post-tax (i.e. disposable) income.[21] The ability of governments to affect income concentration through taxation and transfers may influence public opinion, particularly in European countries with traditionally stronger welfare systems and redistributive policies.[22]

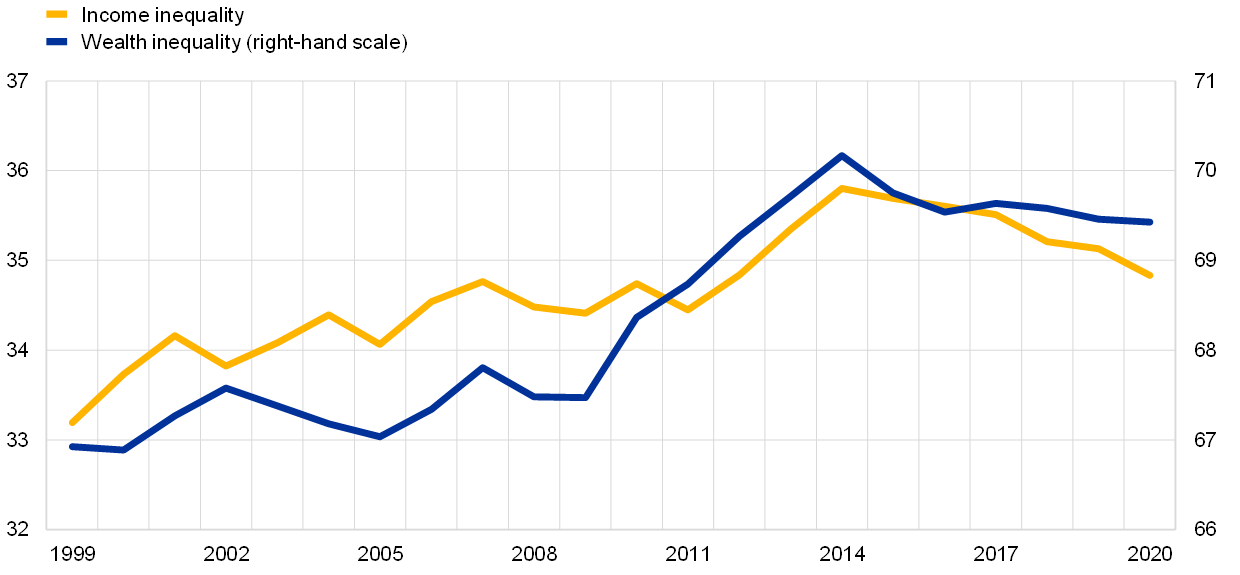

Income and wealth inequality in euro area countries have both increased since 1999, albeit marginally (Chart 1). This trend strengthened in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, with wealth inequality growing more rapidly than income inequality. Both measures peaked in 2014 and have since stabilised.[23]

Chart 1

Income and wealth inequality in euro area countries, 1999-2020

(left-hand scale: post-tax income Gini coefficient; right-hand scale: wealth Gini coefficient)

Source: World Inequality Database.

Note: Average Gini of euro area countries weighted by population size and adjusted for euro area accession.

Individuals are more likely to base their decisions and policy preferences on subjective perceptions of income inequality than on statistical measures. While most people know approximately what their own income is, they generally do not know the entire income distribution or where exactly their income level fits into that distribution.[24] As a heuristic, people tend to relate their own position in the income distribution to a reference group with which they are familiar, often a peer group with a similar socio-economic background, but often perceive themselves as closer to the centre of the distribution than is actually the case. People in the upper part of the distribution tend to believe they are ranked lower, while people in the lower part of the distribution tend to believe they are ranked higher than they actually are.[25]

Individual perceptions of inequality are formed at least partially in line with economic fundamentals. Cross-country research shows a misalignment between subjective impressions and economic inequality captured by statistical indicators.[26] At the same time, recent evidence for OECD countries suggests that, while information on the income distribution is incomplete, perceptions of income disparities seem to reflect real-life evidence of economic inequality.[27] People identify income inequality where statistical estimates also point in this direction.

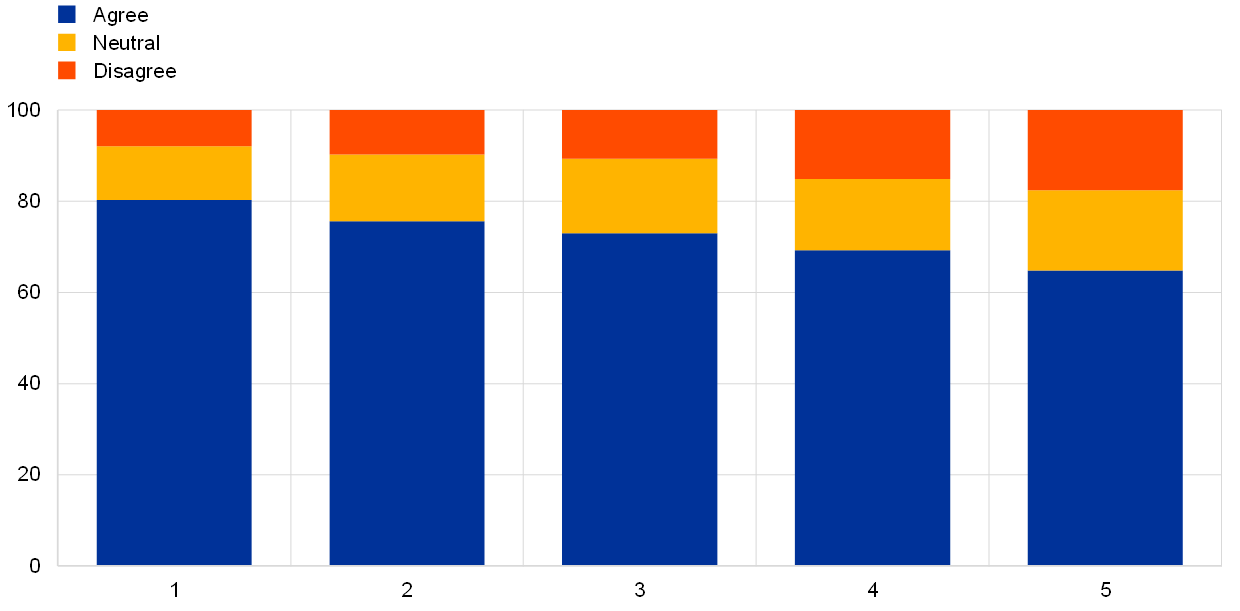

In the six countries surveyed in the ECB’s new Consumer Expectations Survey, a large majority of citizens perceive income inequality as “too large” and their view correlates with their income status. It is important to note that the question in the survey is primarily normative, as it asks respondents to benchmark the current degree of inequality against an ideal one. Consequently, this measure does not necessarily capture the respondent’s perception of the degree of inequality in society. As shown in Chart 2, the share of respondents who perceive inequality as “too large” are in a clear majority in all income quintiles. Looking at individual countries, in Belgium, Spain and Italy more than 75% of the respondents perceive income inequality to be “too large” (not shown). This sentiment is also shared by a majority of respondents across the income distribution in all countries. At the same time, those at the lower end of the income distribution are more likely (by around 15 percentage points) to agree that income inequality is “too large” than those at the upper end. The differences vary across countries, with respondents in Spain and Italy displaying fairly similar views across the income distribution, while there are differences between low and high-income respondents in Belgium, Germany, France and the Netherlands (not shown).

Chart 2

Perception of inequality as “too large”, by income quintile

(percentage share)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey.

Notes: Pooled and weighted data across waves from April 2020 to December 2021 for the six countries included in the survey (Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the Netherlands). The perception of income inequality as “too large” is measured on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 7 is “strongly agree” with the following statement: “Differences in income in the country you currently live in are too large”. Answers 1-3 are included in “Disagree”, 4 in “Neutral” and 5-7 in “Agree”.

4 Public trust in EU institutions and economic inequalities

Establishing a causal relationship between inequality and public trust in the ECB and other EU institutions is challenging. On one hand, a number of confounding variables may affect economic inequality and public trust in institutions simultaneously. For example, differences in education level may lead to higher income inequality. These differences would also be reflected in levels of public trust, since lower levels of education are associated with lower public trust in institutions.[28] Similarly, higher levels of unemployment tend to be associated with both higher income inequality and lower levels of public trust.[29] On the other hand, economic inequality may be endogenous to levels of public trust, as interpersonal trust affects preferences for more or less redistributive policies. For example, the lower levels of income inequality and more generous welfare systems in Scandinavian countries have been traced to higher levels of interpersonal trust,[30] which correlates with institutional trust.[31] This may give rise to a reverse causality problem, making it difficult to disentangle the effects of inequality on trust from the effects of trust on inequality.

This section explores the associations between economic inequalities and public trust at the bivariate level without trying to establish causality. Box 1 examines empirically the association between perceived income inequality and public trust in EU institutions, adding additional control variables to account for possible confounding factors that may affect the relationship between economic inequalities and institutional trust.

The analysis draws on survey data from the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey and the Standard Eurobarometer. The ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey traces public trust in institutions through a monthly panel survey which started in April 2020.[32] This is combined with analysis of data from the Standard Eurobarometer covering 43 waves of the biannual survey.[33] These opinion surveys are the best available sources for measuring public trust in EU institutions and allow quantitative analyses of trends over time and across countries.

Trust in the ECB is explored alongside trust in the European Commission and trust in the European Parliament. Citizens may not differentiate adequately between different EU institutions when expressing their level of trust, and some citizens may therefore evaluate the ECB as part of the overall EU framework.[34] Any relationship between economic inequalities and public trust in the ECB may therefore be due to factors that do not relate solely to the ECB, but are rather part of an overall regime evaluation of the EU. Moreover, we can compare patterns of trust in the ECB with patterns of trust in other EU institutions to identify whether any link between inequality and trust is specific to the ECB.

Box 1

The relationship between perceived income inequality and public trust in EU institutions in the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey

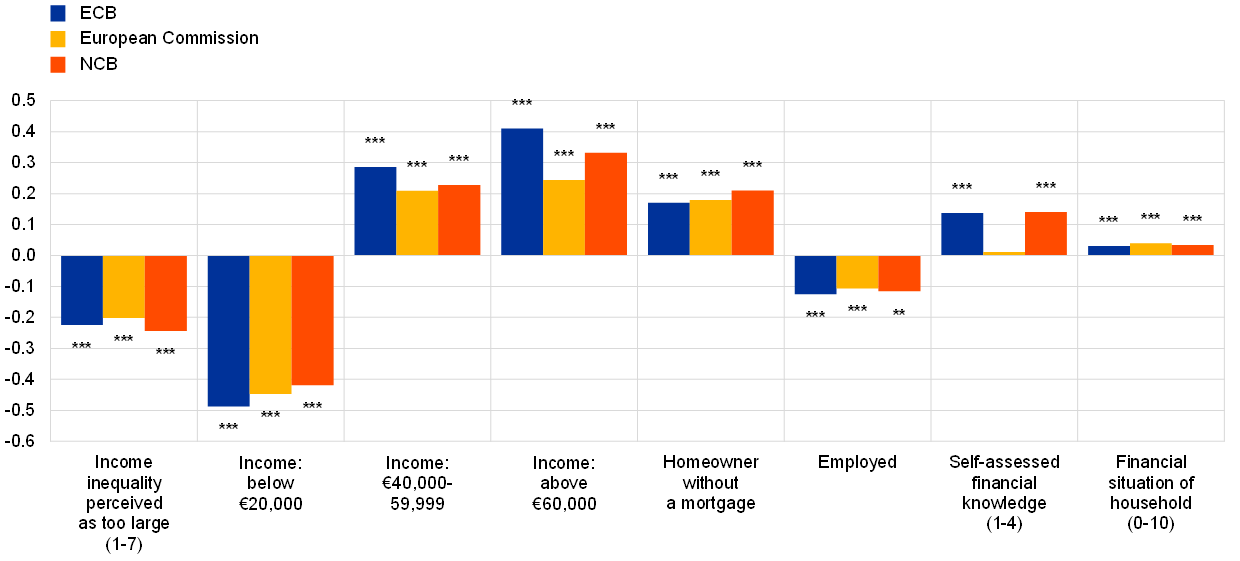

This box examines the association between normative perceptions of income inequality and public trust in EU institutions, controlling for a range of possible confounding variables that may affect this relationship. In doing so, it extends recent analyses of trust in the ECB in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic by including perceptions of income inequality among the explanatory variables. On the basis of a recent study by van der Cruijsen and Samarina[35], we apply a similar random-effects panel regression technique using monthly panel data from the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey for six euro area countries between April 2020 and October 2021. To analyse whether any relationship is specific to the ECB, we estimate the model for trust in the European Commission and national central banks (NCBs) as well as for trust in the ECB.

Perceptions of income inequality being “too large” are negatively associated with public trust in the ECB when controlling for a range of possible confounding factors. The results shown in Chart A suggest that moving one step on a seven point scale of agreement with the statement that income inequality is “too large” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) reduces the level of trust in the ECB by 0.2 points (on a 0-10 scale). While small in magnitude, the negative relationship is statistically significant. Such a negative relationship also applies to public trust in the European Commission and in NCBs, with a similar order of magnitude. This seems to indicate that the negative association is not unique to the ECB and that citizens have similar attitudes towards all institutions. Moreover, the results also show that income levels are positively associated with public trust in the ECB when controlling for other factors, and the same relationship applies to other institutions. Similarly, levels of wealth, as proxied by those who reside in an owner-occupied property without a mortgage, are positively associated with public trust in the ECB and public trust in the European Commission and NCBs (Chart A). The similar results across institutions may also be influenced by the fact that respondents do not differentiate between institutions when answering questions about their levels of trust.

Chart A

Association between trust in EU institutions and perceived inequality

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey.

Notes: The table shows the results of random effects panel regressions, with standard errors clustered at the individual level. Constant wave and country dummies are included (not shown). The regression also controls for gender, age and education (not shown). Trust in the institutions is measured on scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is no trust at all in the institution and 10 is complete trust. The perception of income inequality as “too large” is measured on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 7 is “strongly agree” with the following statement: “Differences in income in the country you currently live in are too large”. Financial situation of household is measured by the question “How concerned are you about the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) on each of the following: The financial situation of your household”, where 0 is not concerned at all and 10 is extremely concerned. Self-assessed financial knowledge is measured by the question “How knowledgeable do you consider yourself on financial matters?”, where 1 is not knowledgeable and 4 is very knowledgeable. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

5 Public trust in EU institutions and inequality

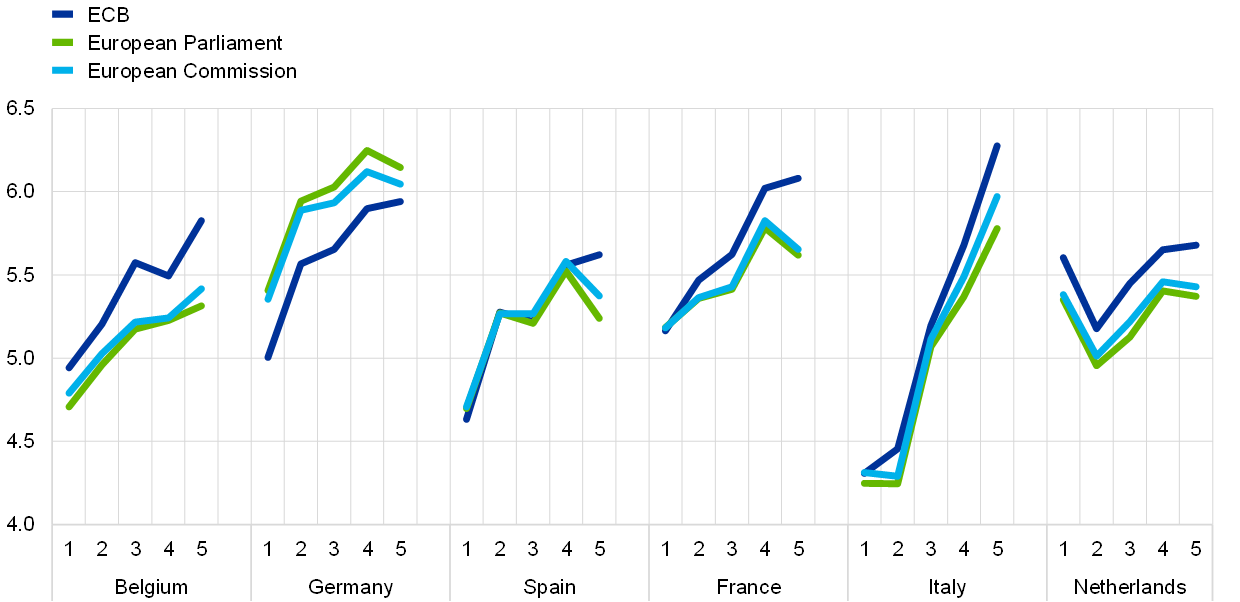

Trust in EU institutions increases with income. Chart 3 breaks down public trust by total household income across the population and shows that in all six countries surveyed average levels of trust in the ECB gradually rise as income increases. This relationship is robust to differences in age, gender, education level and employment status (not shown). Moreover, the same pattern is found for average levels of trust in the European Parliament and the European Commission.[36]

Chart 3

Trust in EU institutions, by household income quintile

(average level of trust)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey.

Notes: The data include monthly waves from April 2020 to December 2021. The weighted average level of trust in the respective institution is measured on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is no trust at all in the institution and 10 is complete trust.

While the differences in levels of trust across the income distribution apply to all six countries and for all three institutions, the strength of the relationship is heterogeneous. The change in the average levels of trust in the ECB along the income distribution is smallest in the Netherlands and largest in Italy. Looking at differences between the ECB and the other EU institutions, it is notable that in France and Italy the average levels of trust in the ECB are more similar to the average levels of trust in the European Parliament and the Commission at the lower end of the income distribution, but slightly higher at the upper end. In Belgium and the Netherlands, trust in the ECB is higher than trust in the other institutions across all income groups, while in Germany it is lower across the distribution.

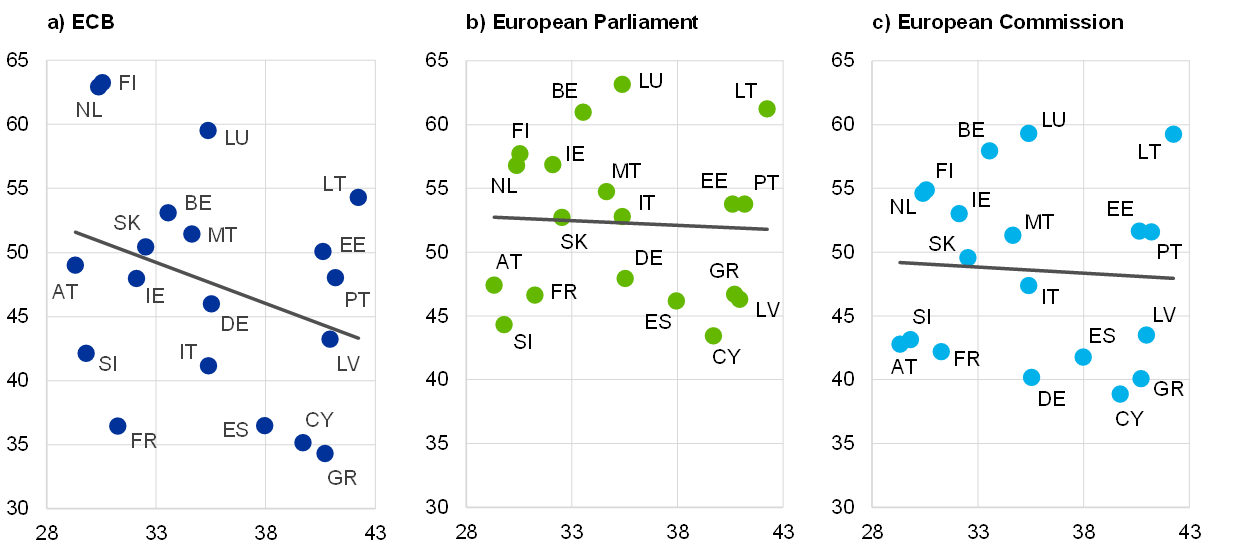

This positive relationship suggests that income levels may matter for public trust in EU institutions, but it does not say much about the relationship between income inequality and public trust. Panel a of Chart 4 indicates that public trust in the ECB tends to be higher in countries with lower income inequality and vice versa. Moreover, the bivariate relationship between the post-tax Gini coefficient and trust is stronger for the ECB than for the European Parliament or the European Commission (panels b and c).

Chart 4

Gini coefficients of post-tax income inequality and trust in EU institutions for euro area countries (1999-2020)

(x-axis: average Gini coefficient of post-tax income inequality; y-axis: average tendency to trust the institution)

Sources: Standard Eurobarometer and World Income Inequality Database.

Notes: Average values between 1999 and 2020 adjusted for euro area accession. Trust in the institution is measured as the share of respondents giving the answer “Tend to trust” to the question “Please tell me if you tend to trust or tend not to trust these European institutions: [NAME OF INSTITUTION]”. The relationship between the average tendency to trust and the average Gini coefficient of post-tax income inequality is statistically significant at the 10% level for the ECB, but insignificant for the European Parliament and the European Commission.

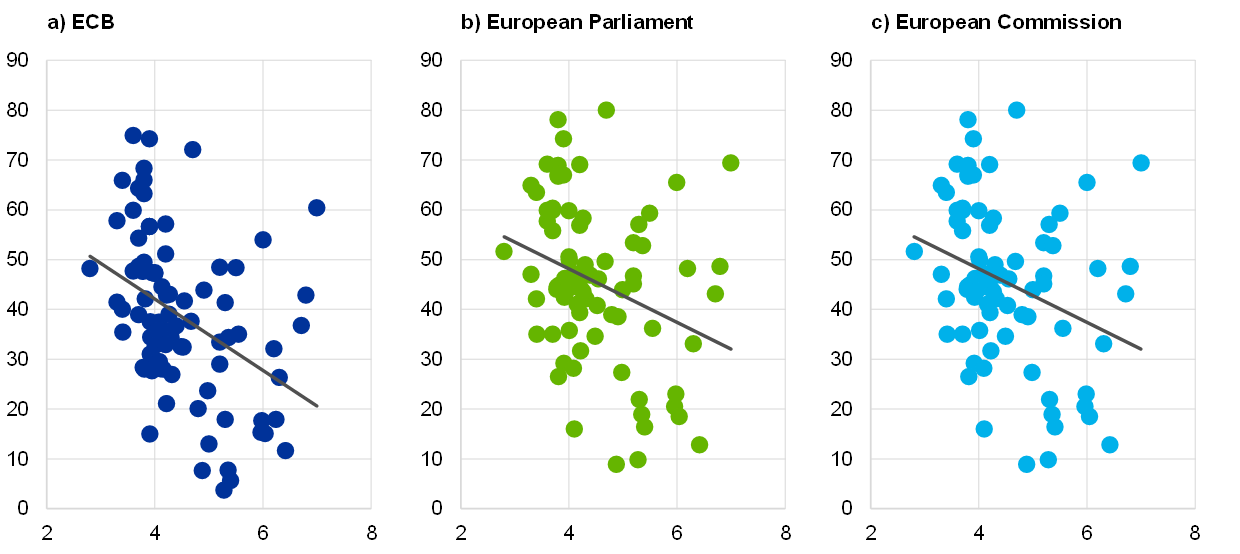

Regional data confirm the negative association between income inequality and public trust in the ECB, thereby supporting the argument that the level of income inequality is a relevant factor. Public trust in the ECB is lower in regions with large differences between the highest and lowest earners than in regions where the differences are smaller (Chart 5, panel a). This relationship also applies to levels of public trust in the European Parliament and the European Commission (panels b and c). Compared to measures of income inequality at the country level, regional measures of income inequality may be closer to the level of inequality that citizens perceive to be relevant for them and therefore have more influence on their general attitudes.

Chart 5

Income quintile share ratio (S80/S20) and trust in EU institutions in regions within the euro area (NUTS1/2)

(x-axis: income quintile share ratio within regions; y-axis: tendency to trust)

Sources: Standard Eurobarometer, Eurostat and OECD.

Notes: The income quintile share ratio measures the ratio of the total income received by the 20% of the population with the highest income (top quintile) to the income received by the 20% of the population with the lowest income (bottom quintile) within the region. The chart shows income quintile share ratios within regions at NUTS1 level for Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy and the Netherlands and at NUTS2 level for Ireland, Spain, France, Lithuania, Austria, Slovenia, Slovakia and Finland. The observations are the latest available for each country (2019 for Belgium, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Slovakia; 2018 for Austria; 2013 for Germany and Spain; 2010 for France). The income quintile share ratios have been winsorised at the 1st and 99th percentiles to account for outliers. The tendency to trust each institution has been aggregated at the corresponding NUTS level and year (combining the autumn and spring survey waves of the Standard Eurobarometer), and regions with less than 45 observations have been excluded. Observations are missing for Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta and Portugal. The relationship between public trust and the income quintile share ratio is statistically significant at the 1% level for all institutions.

Measures of wealth inequality show a less pronounced relationship with trust in EU institutions. Compared to measures of the distribution of income, measures of levels of household wealth and its distribution are both less available and not as accurate, owing to the challenges in collecting such information through surveys and administrative data. When plotting wealth inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient for net personal wealth) against public trust in the ECB in euro area countries between 1999 and 2020, no clear relationship emerges.

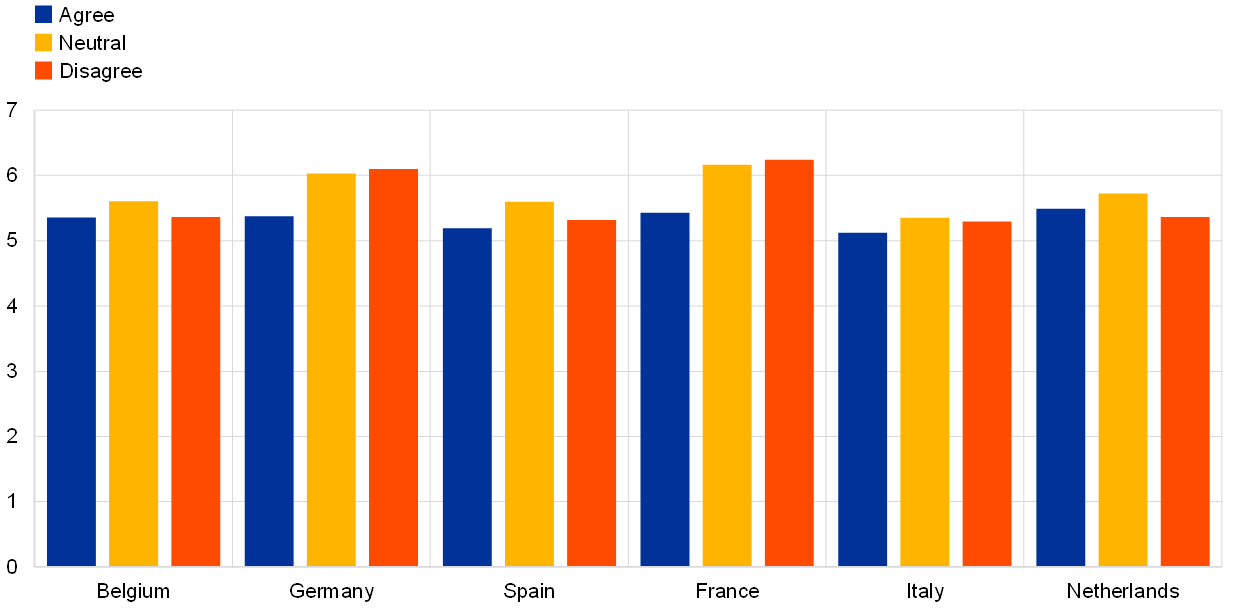

Finally, citizens who perceive income inequality as “too large” tend to show slightly lower levels of trust in the ECB and other EU institutions. As discussed in Section 3, statistical measures of income inequality may not be known to all citizens, who may instead base their policy preferences and attitudes on their subjective and varying perceptions of income inequality. Chart 6 shows that, on average, German and French citizens who perceive inequality as “too large” display lower levels of trust in the ECB than those who are neutral or disagree with the statement. This relationship remains the same when accounting for differences in age, gender, education level and employment status (not shown). However, in Belgium, Spain, Italy and the Netherlands, the differences in average levels of trust in the ECB across the different views are fairly small. A similar pattern is also found for trust in the European Commission and the European Parliament (not shown).

Chart 6

Public trust in the ECB, by perception of inequality as “too large”

(average level of trust)

Source: ECB Consumer Expectations Survey.

Notes: The data include monthly waves from April 2020 to December 2021. The perception of income inequality as “too large” is measured on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 7 is “strongly agree” with the following statement: “Differences in income in the country you currently live in are too large”. Answers 1-3 are included in “Disagree”, 4 in “Neutral” and 5-7 in “Agree”.

6 Conclusion

Income and wealth inequality have risen in many advanced economies over recent decades and the pandemic may further increase existing economic inequalities. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic risks amplifying existing economic inequalities, as some segments of the population are more exposed to unemployment and loss of income, while rising asset prices could exacerbate wealth inequality.

While economic inequality has attracted increased attention in academic research and policy discussions recently, less attention has been paid so far to its relationship with public trust in central banks. Responsibility for addressing social inequalities rests primarily with governments, but citizens may also expect central banks to take action, and their attitudes towards the central bank may therefore be influenced by objective and subjective measures and perceptions of economic inequality.

Tentative evidence suggests that higher income inequality, as well as associated perceptions, may matter for public trust in the ECB. Trust in the ECB tends to be lower in countries with higher income inequality and vice versa. Similarly, at the regional level, public trust in the ECB tends to be lower in regions with larger differences between the highest and lowest earners. Finally, at the individual level, citizens who perceive income inequality as being “too large” tend to show slightly lower levels of trust in the ECB. While small in magnitude, the negative relationship is statistically significant and holds when controlling for possible confounding factors.

However, inequality appears to play a role not only in citizens’ evaluations of the ECB but also in their evaluations of EU institutions more broadly. As shown in this article, the relationship between public trust in the ECB and income inequality also applies to other EU institutions, such as the European Parliament and the Commission. This is in line with studies showing that attitudes towards different EU institutions tend to be highly correlated, suggesting that citizens may be evaluating the overall EU framework when asked about specific institutions.[37]

Efforts to improve public understanding of the ECB’s mandate and tasks may help foster trust in the institution. Making communication more accessible and addressing the concrete concerns of citizens in different parts of the euro area – such as the ECB’s role in economic outcomes – can enhance trust in the ECB, thereby strengthening the effectiveness of its monetary policy tools and helping to safeguard its independence. This effort includes explaining how the ECB’s policies, by delivering on its primary objective of price stability as laid down in the Treaty, contribute to macroeconomic stabilisation and can affect economic inequality. Indeed, inflation is often considered one of the most regressive “taxes”, and by maintaining price stability the ECB protects the purchasing power of households with lower incomes who are the most sensitive to fluctuations in the level of prices. In parallel, like many central banks, the ECB is also continuing to deepen its analysis of how its policies affect inequality and the manner in which household heterogeneity shapes the transmission of its policies.[38]

See, for example, Alvaredo, F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E. and Zucman, G., “Global Inequality Dynamics: New Findings from WID.world”, American Economic Review, Vol. 107, No 5, 2017, pp. 404-409; Blanchet, T., Chancel, L. and Gethin, A., “Why is Europe more equal than the United States?”, World Inequality Lab Working Papers, No 2020/19, 2020; Piketty, T. and Saez, E., “Inequality in the long run”, Science, Vol. 344, No 6186, 2014, pp. 838-843; Nolan, B. and Valenzuela, L., “Inequality and its discontents”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 35, No 3, 2019, pp. 396-430; and Zucman, G., “Global Wealth Inequality”, Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 11, No 1, 2019, pp. 109-138.

See, for example, the box entitled “COVID-19 and income inequality in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2021; and the article entitled “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the euro area labour market”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2020.

For more information, see also Schnabel, I., “Monetary policy and inequality”, speech at a virtual conference on “Diversity and Inclusion in Economics, Finance, and Central Banking”, 9 November 2021.

See ECB Listens – Midterm review summary report, ECB, 2021; and ECB Listens – Summary report of the ECB Listens Portal responses, ECB, 2022.

See the article entitled “Monetary policy and inequality”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2021. While the evidence on the effects on income inequality is more conclusive, the evidence on wealth distribution is less so. See Schnabel, I., op. cit.

See, for example, Kuhn, T., van Elsas, E., Hakhverdian, A. and van der Brug, W., “An ever wider gap in an ever closer union: Rising inequalities and euroscepticism in 12 West European democracies, 1975-2009”, Socio-Economic Review, Vol. 14, No 1, 2016, pp. 27-45; and Lipps, J. and Schraff, D., “Regional inequality and institutional trust in Europe”, European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 60, No 4, 2021, pp. 892-913. Moreover, several studies have shown that rising economic inequality tends to increase political support for populist parties, thereby having an impact on EU policymaking. See, for example, Guriev, S., “Economic Drivers of Populism”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 108, 2018, pp. 200-203.

Higher levels of public trust can help to anchor inflation expectations of economic actors around the inflation target, thereby ensuring that temporary deviations of realised inflation from the target do not influence wage demands and price-setting decisions of households and firms. See, for example, Christelis, D., Georgarakos, D., Jappelli, T. and van Rooij, M., “Trust in the Central Bank and Inflation Expectations”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 16, No 6, 2021, pp. 1-37; Rumler, F. and Valderrama, M.T., “Inflation literacy and inflation expectations: Evidence from Austrian household survey data”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 87, 2020, pp. 8-23; and van der Cruijsen, C. and Samarina, A. “Trust in the ECB in turbulent times”, DNB Working Paper, No 722, De Nederlandsche Bank, 2021.

See, for example, Andersen, R., “Support for democracy in cross-national perspective: The detrimental effect of economic inequality”, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, Vol. 30, No 4, 2012, pp. 389-402; Gould, E. and Hijzen, A., “Growing Apart, Losing Trust? The Impact of Inequality on Social Capital”, IMF Working Papers, No 16/176, International Monetary Fund, 2016; and Krieckhaus, J., Son, B., Bellinger, N. and Wells, J., “Economic Inequality and Democratic Support”, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 76, No 1, 2014, pp.139-151.

For example, societies with higher levels of inequality also tend to be more accepting of more unequal income distributions. On the other hand, a rise in inequality may have a greater impact on trust in institutions in countries with low initial levels of inequality than in countries with high initial levels of inequality. See Sachweh, P. and Olafsdottir, S., “The Welfare State and Equality? Stratification Realities and Aspirations in Three Welfare Regimes”, European Sociological Review, Vol. 28, No 2, 2012, pp. 149-168.

See Ervasti, H., Kouvo, A. and Venetoklis, T., “Social and Institutional Trust in Times of Crisis: Greece, 2002-2011”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 141, 2019, pp. 1207-1231.

See Kumlin, S. and Haugsgjerd, A., “The welfare state and political trust: bringing performance back in”, in Zmerli, S. and van der Meer, T.W.G. (eds.), Handbook on Political Trust, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, 2017, pp. 285-301.

See, for example, Knell, M. and Stix, H., “Perceptions of inequality”, European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 65, 2020.

See descriptive results in, for example, Dion, M.L. and Birchfield, V., “Economic Development, Income Inequality, and Preferences for Redistribution”, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 54, No 2, 2010, pp. 315-334; and Olivera, J., “Preferences for redistribution in Europe”, IZA Journal of European Labor Studies, Vol. 4, No 14, 2015.

There is evidence that inequality has stronger negative effects on institutional trust among citizens with more egalitarian values. See Anderson, C.J. and Singer, M.M., “The Sensitive Left and the Impervious Right: Multilevel Models and the Politics of Inequality, Ideology, and Legitimacy in Europe”, Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 41, No 4/5, 2008, pp. 564-599.

See, for example, Goubin, S. and Hooghe, M., “The Effect of Inequality on the Relation Between Socioeconomic Stratification and Political Trust in Europe”, Social Justice Research, Vol. 33, 2020, pp. 219-247.

See ECB Listens – Midterm review summary report, ECB, 2021.

Looking at representative survey data collected in Germany in 2018, it was observed that respondents who trust the ECB were more likely to believe that its asset purchase programme had no effect or a reducing effect on inequality in Germany and that it improved their personal economic situation. See Hayo, B., “Does Quantitative Easing Affect People’s Personal Financial Situation and Economic Inequality? The View of the German Population”, SSRN, 2020.

See Bonasia, M., Canale, R.R., Liotti, G. and Spagnolo, N., “Trust in Institutions and Income Inequality in the Eurozone: The Role of the Crisis”, Engineering Economics, Vol. 27, No 1, 2016, pp. 4-12.

See Farrell, L., Fry, J.M. and Fry, T.R.L., “Who trusts the bank of England and high street banks in Britain?”, Applied Economics, Vol. 53, No 16, 2021, pp. 1886-1898.

See, for example, Piketty, T. and Saez, E., op. cit. For an account of how the trends of income and wealth inequality differ in the United States, see Kuhn, M., Schularick, M. and Steins, U.I., “Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949-2016”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 128, No 9, 2020, pp. 3469-3519.

For both income and wealth inequality, the Gini coefficient is a standard – but not the sole – indicator of how much the distribution of income or wealth deviates from perfect equality.

For a review of the measurement of inequality, see McGregor, T., Smith, B. and Wills, S., “Measuring inequality”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 35, No 3, 2019, pp. 368-395.

For more details on these trends, see Blanchet, T., Chancel, L. and Ghetin, A., “How Unequal is Europe? Evidence from Distributional National Accounts, 1980-2017”, WID.world Working Paper, No 2019/06, 2019.

See Gimpelson, V. and Treisman, D., “Misperceiving inequality”, Economics & Politics, Vol. 30, No 1, 2018, pp. 27-54.

This tendency is called centre bias and represents a recurring misconception of subjective interpretations of income inequality. See Hvidberg, K.B., Kreiner, C. and Stantcheva, S., “”,Social Positions and Fairness Views on Inequality”, NBER Working Paper, No 28099, November 2021; and Cruces, G., Perez-Truglia, R. and Tetaz, M., “Biased perceptions of income distribution and preferences for redistribution: Evidence from a survey experiment”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 98, 2013, pp. 100-112.

See Cruces, G. et al., op. cit.; and Kuhn, A., “The Individual Perception of Wage Inequality: A Measurement Framework and Some Empirical Evidence”, IZA Discussion Paper Series, No 9579, IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn, 2015.

Does Inequality Matter? How People Perceive Economic Disparities and Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021.

See, for example, Ehrmann, M., Soudan, M. and Stracca, L., “Explaining European Union Citizens’ Trust in the European Central Bank in Normal and Crisis Times”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 115, No 3, 2013, pp. 781-807; and Bergbauer, S., Hernborg, N., Jamet, J.-F. and Persson, E., “The reputation of the euro and the European Central Bank: interlinked or disconnected?”, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 27, No 8, 2020.

See, for example, Roth, F. and Jonung, L., “Public Support for the Euro and Trust in the ECB: The first two decades of the common currency”, Hamburg Discussion Papers in International Economics, No 2, 2019.

See, for example, Algan, Y., Cahuc, P. and Sangnier, M., “Efficient and Inefficient Welfare States”, IZA Discussion Paper Series, No 5445, IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn, 2011.

See Angino, S., Ferrara, F. and Secola, S., “The cultural origins of institutional trust: The case of the European Central Bank”, European Union Politics, 2021.

While being limited in time and geographic scope (covering only Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the Netherlands) this survey reports public trust on a 0-10 scale, allowing for a more precise analysis of this variable than binary indicators. In addition, the survey includes a range of information on the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and economic expectations, including levels of total household income and perceptions of inequality. For more information on the survey, see Bańkowska, K. et al., “ECB Consumer Expectations Survey: an overview and first evaluation”, Occasional Paper Series, No 287, ECB, December 2021.

The Eurobarometer asks the following question: “Please tell me if you tend to trust or tend not to trust these European institutions: [NAME OF INSTITUTION]”. The data are aggregated at the country level and the regional level for euro area countries by year, combining the regular spring and autumn waves. The data for 2020 only include one wave as the regular pattern of two surveys per year was disrupted by the pandemic.

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, both national and European institutions experienced a decline in public trust as part of a broader trend in which citizens became increasingly sceptical of policymakers. See the box entitled “Developments in trust in public institutions since the global financial crisis”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2020.

See van der Cruijsen, C. and Samarina, A., op. cit.

A comparison with data from the European Social Values Survey, which measures only trust in the European Parliament, confirms that the average level of trust in the European Parliament increases across the income distribution. This pattern also applies to levels of trust more broadly, including trust in NCBs and generalised levels of trust in other people (interpersonal trust).

See Ehrmann, M., Soudan, M. and Stracca, L., op. cit.

See the article entitled “Monetary policy and inequality”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, 2021.