Fiscal spillovers in a monetary union

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1/2019.

The article describes the main transmission channels of the spillovers of national fiscal policies to other countries within a monetary union and investigates their magnitude using different models. In the context of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), fiscal spillovers are relevant for the accurate assessment of the cyclical outlook in euro area countries, as well as in the debates on a coordinated change in the euro area fiscal stance and on euro area fiscal capacity. The article focuses on spillovers from expenditure-based expansions in the larger euro area countries by presenting two complementary exercises. The first is an empirical investigation of spillovers based on a new, long dataset for the largest euro area countries, while the second uses a multi-country general equilibrium model with a rich fiscal specification and the capacity to analyse trade spillovers. Fiscal spillovers are found to be heterogeneous but generally positive among the larger euro area countries. The reaction of interest rates to fiscal expansion is an important determinant for the magnitude of spillovers.

1 Introduction

Fiscal spillovers across countries have received increasing attention in recent years. Understanding the impact of one country’s fiscal policies on output in other Member States of the monetary union is naturally of considerable interest to a central bank setting a single monetary policy, as it allows the bank to better gauge the euro area’s economic developments, and this feeds into the assessment of the risks to price stability. Moreover, fiscal spillovers should be taken into account when assessing the aggregate euro area fiscal stance.[1] Finally, the size of the fiscal spillovers is important when assessing the stabilisation effects of national fiscal policies. If the fiscal spillovers are small, then the existence of a central fiscal stabilisation function that can support national economic stabilisers in the presence of large economic shocks would make the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) more resilient.[2]

National fiscal policies spill over to other countries through different channels. Trade is an important transmission channel between countries, whereby fiscal expansion in one country increases its imports from other countries. Fiscal expansion could also increase domestic prices and the real effective exchange rate, reinforcing spillovers, as the stimulating country loses competitiveness vis-à-vis the other countries. Given the implications for prices, it is important to take into account the monetary policy response. Interest rates may occasionally not react to price changes stemming from fiscal action, for instance, if the economy is constrained by the effective lower bound.[3]

The empirical literature on fiscal spillovers is relatively underdeveloped. While the number of empirical studies of the magnitude of fiscal spillovers has grown in recent years, it is limited and results are not easily comparable. The different identification of fiscal shocks and presentation of the results according to different metrics add to the complication of generalising the findings from the literature. One purpose of this article is to provide a review of the most relevant empirical literature on spillovers. For simplicity we assume an expenditure-based fiscal expansion in our analysis.[4]

Spillover estimates of public spending tend to be positive but generally small. A number of studies have estimated fiscal spillovers from an increase in public spending through the trade channel for a panel of countries. For example, based on annual data from 1965 to 2004, Beetsma, Giuliodori and Klaassen estimate that a spending-based fiscal expansion of 1% of GDP in Germany would lead to an average increase in the output of other European economies by 0.15% after two years; for an expansion originating in France, the impact is 0.08%.[5] Using quarterly data from 2000 to 2016 for 55 countries, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reports that an increase in government spending by 1% of GDP in an average major advanced economy has a spillover effect of 0.15% of GDP on an average recipient country within the first year.[6] Auerbach and Gorodnichenko find fiscal spillovers from large OECD economies that are broadly comparable with the IMF findings.[7]

Spillover estimates are heterogeneous. The estimated magnitude of spillovers varies, with the heterogeneity related to the trade links, the state of the economy and the reaction of monetary policy. Beetsma et al. find spillovers from Germany to be around 0.4% of GDP after two years in small open economies sharing a land border with the country, such as Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands. Auerbach and Gorodnichenko find spillovers particularly high in recessions and quite modest in expansions. The IMF study finds that spillovers are up to four times as large when monetary policy is at the effective lower bound (0.3% after one year), compared with normal times (0.08%).[8]

Additional insight into fiscal spillovers is provided by a number of studies using theoretical dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models. Rich DSGE multi-country models can provide more insight into the determinants of the fiscal spillovers than empirical methods such as vector auto-regressions (VARs), which encompass a variety of contributing effects that are difficult to disentangle. However, DSGE models may come at the price of imposing restrictive assumptions, which may not always have strong empirical foundations. Studies based on DSGE models often find spillovers in normal times to be lower than the VAR-based estimates, but higher when interest rates do not react.[9] This is partly explained by the fact that structural models only include spillovers through trade, whereas VARs also include other effects, such as financial spillovers.

2 Empirical Estimates

This section presents new estimates of fiscal spillover effects from the larger euro area countries. To this end, country-specific exogenous government spending shocks are identified and their dynamic effect on the economic activity of other countries considered.[10]

2.1 Data and methodology

Estimates are based on a new dataset for euro area countries. An analysis of the effects of fiscal spillovers based on time series methods requires the use of comparable, long and detailed data. However, for euro area countries, data on many of the necessary fiscal variables are only available at a quarterly frequency from the mid- to late 1990s. This issue is addressed by assembling a new dataset for Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the euro area as a whole, from the first quarter of 1980 to the fourth quarter of 2015 at a quarterly frequency, which is consistent with Eurostat data (in the current ESA 2010 accounting framework). In particular, using an unobserved component model that combines both annual and quarterly national accounts, as well as monthly indicators, it is possible to estimate fiscal variables at a quarterly frequency while maintaining coherence with official annual aggregates. This framework takes into account important features of the data, such as different seasonal patterns.[11]

The resulting dataset contains disaggregated measures of fiscal spending (and revenues) for each of the four countries and the euro area aggregate. This disaggregation allows the separation of components of government spending depending on their sensitivity to economic conditions. In the further analysis the government spending aggregate comprises cyclically insensitive items, in particular government consumption and investment, while cyclically sensitive items such as transfers are excluded.[12]

The empirical strategy follows three steps. First, country-specific VARs are estimated based on (the logs of) real net tax revenues, government spending, output, the GDP deflator and the level of the ten-year interest rate. The identifying assumption is that it takes longer than one quarter to implement fiscal policies in response to a change in the economic environment, which allows the identification of structural shocks to government spending (i.e. fiscal actions are contemporaneously unrelated to the economic conditions).[13] Second, the dynamic response of economic activity in a country to a government spending shock originating in another country is traced using local projections.[14] This framework allows the estimation of the bilateral effect of the fiscal action for each combination of two countries. Third, these pair-wise estimates are combined into two statistics that summarise the results.

Spillovers are summarised by destination and by origin. Destination spillovers measure the spillover from a simultaneous spending shock in all but one euro area country on the recipient country. They are constructed as the ratio of the (cumulative) sum of the total impact on the output of a given country originated by fiscal actions in the rest of the countries to the sum of the respective domestic effects in the originating countries.[15] Spillover by origin is defined as the ratio of the (output-weighted average) impact on the output in the receiving countries and the impact of a government spending shock on output in the originating country. This statistic indicates the magnitude of the spillovers that each individual country is able to generate.

2.2 Results

The results provide evidence of positive fiscal spillovers in the euro area. Chart 1 plots the GDP response in each of the four economies to increases in government spending in the rest of countries (i.e. the destination spillover). The blue line shows the output response in the receiving country to the government spending shocks in the source countries. Cumulating these output effects and dividing them by the cumulated response of government spending in the stimulating countries (not shown) converts them into a measure that is directly comparable with the multiplier of a domestic fiscal expansion. For example, France has a cumulative destination spillover of 0.72 after two years. This means a simultaneous €1 increase in government spending in Germany, Italy and Spain would increase French output by €0.72 after two years.

Chart 1

Empirical estimates of spillover effects (by destination)

Output response to a simultaneous increase in government spending in the rest of the countries

(x-axis: quarters; y-axis: percentage change)

Source: Alloza et al, 2018.

Note: The blue line shows the output response. The dark grey and light grey lines represent Newey-West confidence intervals at 68% and 95%.

The results are comparable with previous empirical studies. Taking the output-weighted results in Chart 1, the average destination spillovers to large euro area countries are around 0.09, 0.46 and 0.60 in the first, second and third years respectively. These last results are somewhat lower but broadly comparable with those of Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, with which they are methodologically comparable.

There are differences in dynamics, magnitude and significance of destination spillovers across countries. France and Spain show a similar pattern, with the spillover becoming positive and significant at the 68% level by the end of the first year. In both cases the dynamics are similar: around 0.2-0.3 in the first year and cumulatively around 0.6-0.7 in the second year. Germany also shows an increasing positive spillover, but with significant values at the 68% level, only in the third year. While only marginally significant, the magnitude of the effect in Germany seems to be larger than in the rest of the countries considered, with a cumulative destination spillover of 0.6 at the end of the first year. The spillover in Italy is estimated to be the lowest and not significantly different from zero. If the 95% confidence level were applied, then fiscal spillovers would only be significant in the case of Spain.

Positive spillovers are also found for spending increases in one country. When looking at the spillover effect from the point of view of the country conducting the fiscal expansion, i.e. spillovers by origin, the results are heterogeneous but also provide evidence of positive fiscal spillovers among large euro area countries (results not shown here).[16]

3 Spillover analysis based on a multi-country DSGE model

This section provides simulations with a multi-country DSGE model: the Euro Area and Global Economy (EAGLE) model. The model is calibrated for the four largest euro area countries individually (Germany, France, Italy and Spain), the rest of the euro area and the rest of the world.[17] Like the European Central Bank’s New Area-Wide Model, EAGLE is micro-founded and features nominal price and wage rigidities, capital accumulation, and international trade in goods and bonds. Given its global dimension, the model is particularly well suited to assess cross-border spillovers. All regions trade with each other in intermediate goods, with estimates of bilateral trade flows based on recent historical averages. International asset trade is limited to nominally non-contingent bonds denominated in US dollars.

The version used here embeds an extended fiscal bloc.[18] Households are assumed to derive utility from the consumption of a composite good consisting of public and private consumption goods. It is also assumed that the government capital stock affects the production process. Moreover, in each country, public debt is stabilised through a fiscal rule that induces the endogenous adjustment of fiscal instruments when the public debt ratio deviates from its target.

Members of the euro area share a common nominal exchange rate and a common nominal interest rate. The central bank sets the domestic short-term nominal interest rate according to a standard Taylor-type rule, by reacting to area-wide consumer price inflation and real activity. The remaining region – the rest of the world – has its own nominal interest rate and nominal exchange rate.

The simulations focus on government consumption and public investment separately. The following two sections show the spillovers of a two-year spending-based fiscal stimulus, which is debt-financed, for two alternative specifications: first, with interest rates set according to the Taylor rule; second, with unchanged interest rates. The results are shown for government consumption and public investment separately.

3.1 Spillovers by origin and destination

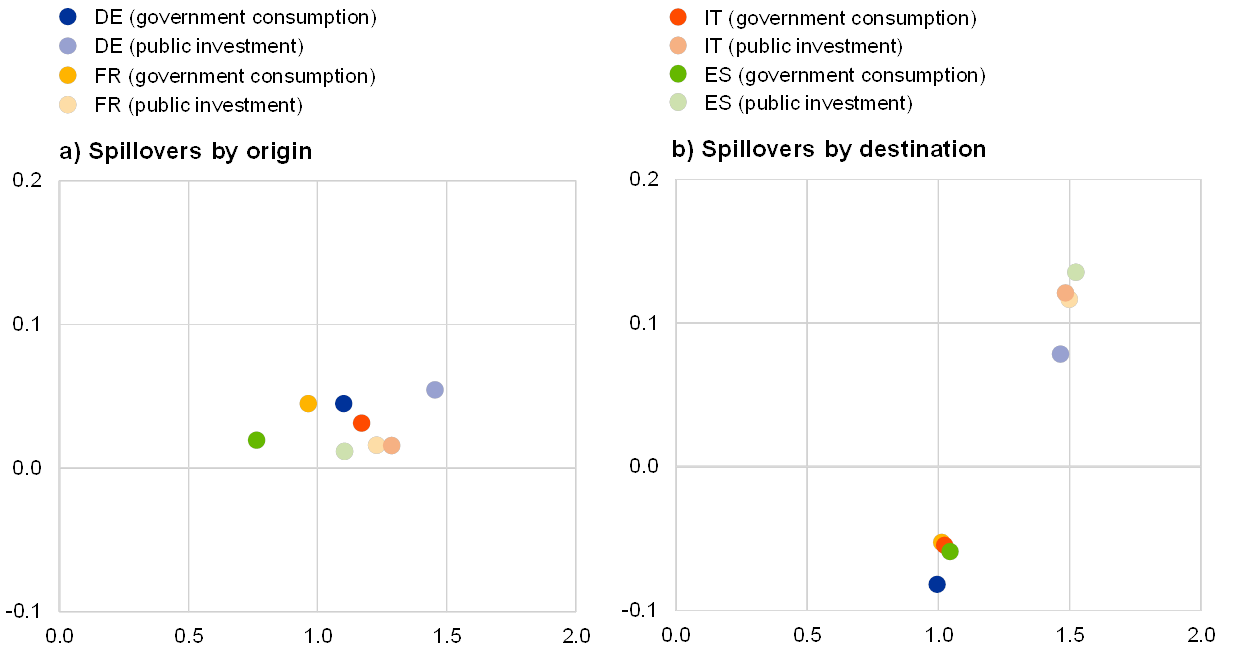

When interest rates follow Taylor rule prescriptions, spillovers by origin are positive but small. The left-hand panel in Chart 2 shows the spillovers from a fiscal stimulus of 1% of nominal GDP over two years in one large euro area country to the rest of the euro area, both for government investment and for consumption.[19] While there is some cross-country heterogeneity, both in the domestic effect (shown on the x-axis) and the effect on the other countries (y-axis), the spillovers (computed as the ratio of GDP reaction of destination to source) are below 0.1 on average in the two years after the shock.

Chart 2

Model simulations of fiscal spillovers (with reactive interest rates)

(x-axis: two-year average percentage change in GDP in country(-ies) propagating the fiscal stimulus; y- axis: two-year average percentage change in GDP in recipient country)

Source: EAGLE model.

Notes: The left-hand panel shows the spillover by origin, i.e. the impact of an increase in government consumption or public investment by 1% of GDP for two years in one country on its own output (x-axis) and the output of the other countries (y-axis). The right-hand panel shows the spillover by destination, i.e. the impact of a simultaneous increase in government consumption or public investment by 1% of GDP for two years in all but one country on the countries’ output (x-axis) and the country receiving the spillovers (y-axis).

Spillovers by destination are also small. The right-hand panel in Chart 2 shows the spillovers in one large country from a simultaneous fiscal stimulus of 1% of GDP over two years in the other countries. For public investment the spillovers come out at just above 0.1. For public consumption the destination spillovers are, on average, slightly negative during the first two years, mainly because the demand effect of the fiscal stimulus is offset by the contractionary impact of higher interest rates that applies to all countries in the monetary union. Relative country size also matters: the destination spillover in Spain is somewhat larger than the destination spillover in Germany, as the former results from a 1% of GDP stimulus in all countries but Spain and the latter from a 1% of GDP fiscal expansion in all countries but Germany.

Destination spillovers are not identical to an aggregation of the spillovers by origin. Both the domestic effect on output in the countries conducting the stimulus and the spillovers are more clustered. An explanation is that the impact of a simultaneous stimulus on prices and economic activity is larger and triggers a relatively stronger monetary reaction than a stimulus in one large euro area country.

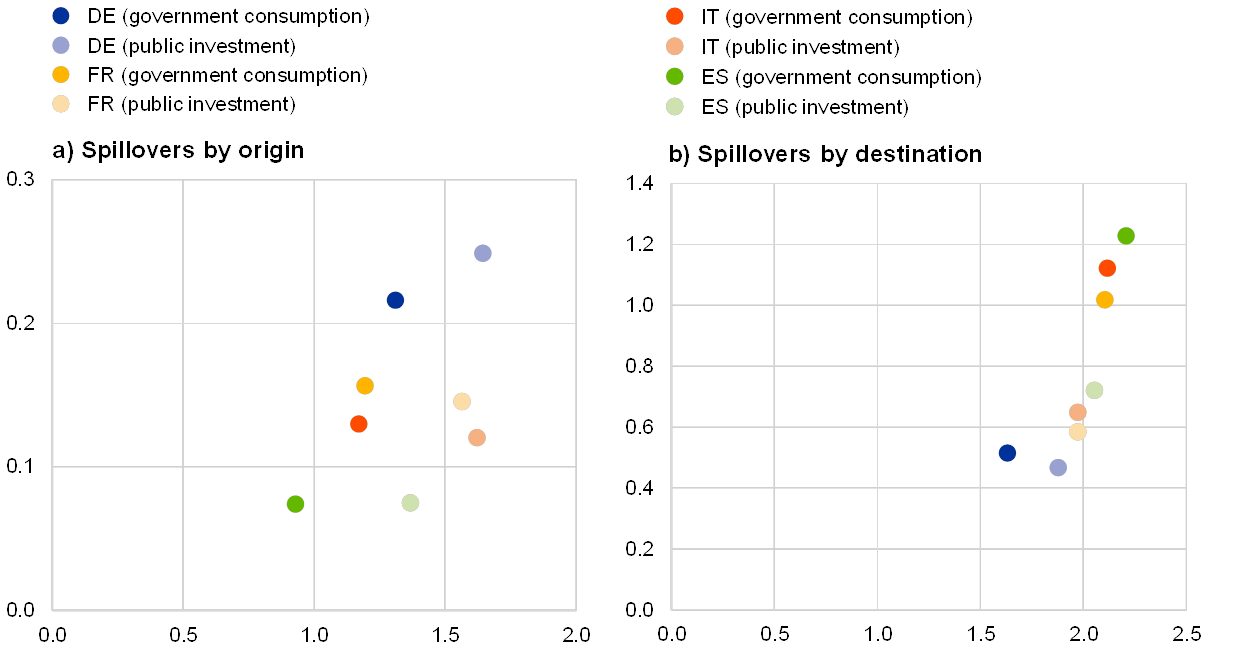

When interest rates in the euro area do not respond to the fiscal shock, spillovers by origin and by destination are positive, and much larger than in the case of reactive monetary policy. Without a reaction by interest rates for two years, spillovers by origin vary between 0.07 for an increase in government consumption in Spain by 1% of GDP and 0.25 for a similar increase in German public investment (see the left-hand panel in Chart 3). These spillovers are around six times as large as those with responsive interest rates. A similarly strong increase can be seen for investment-based spillovers by destination (see the right-hand panel in Chart 3). The sensitivity of destination spillovers to France, Italy and Spain to the reaction of interest rates is even stronger for a public consumption-based stimulus, with the effect increasing from a negative value to above 1.[20]

The model simulations largely confirm the empirical estimates presented above. When interest rates react, spillovers are generally positive but small, and higher for investment than for consumption. When comparing the model simulations with the empirical estimates of the destination spillovers, it should be taken into account that the empirical estimates are based on data covering different monetary policy regimes and without coordinated fiscal policies (except in the 2009-10 period of the crisis). The relatively high empirical destination spillovers for Germany might partially reflect the fact that fiscal stimulus episodes in the other large euro area countries resulted less often in an increase in interest rates, on account of exchange rate pegs to the Deutsche Mark prior to EMU or their smaller weight in the euro area economy since the introduction of a common monetary policy.

Chart 3

Model simulations of fiscal spillovers (with non-reactive interest rates)

(x-axis: two-year average percentage change in GDP in country(-ies) propagating the fiscal stimulus; y- axis: two-year average percentage change in GDP in recipient country)

Source: The EAGLE model.

Notes: The left-hand panel shows the spillover by origin, i.e. the impact of an increase in government consumption or public investment by 1% of GDP for two years in one country on its own output (x-axis) and the output of the other countries (y-axis). The right-hand panel shows the spillover by destination, i.e. the impact of a simultaneous increase in government consumption or public investment by 1% of GDP for two years in all but one country on the countries’ output (x-axis) and the country receiving the spillovers (y-axis).

3.2 Sensitivity analysis

Structural models are sensitive to the assumptions regarding the future evolution of monetary policy. The simulations above are conducted under the assumptions of perfect foresight and complete financial markets. The implication of these assumptions is that the monetary authority, firms and households all know and are able to completely adjust to future changes in the monetary and fiscal policy stances. Through these features, structural models are known to be very sensitive to the announcement of future interest rates, which is known in the theoretical literature as the “forward guidance puzzle”.[21]

Spillovers are also affected by the forward guidance puzzle. The sensitivity to future interest rates does not only apply to the domestic effect of a fiscal stimulus but also to the spillover ratio – the ratio of the average percentage change in GDP in the recipient country to the percentage change in GDP in the stimulating country. An illustration for a public investment-based stimulus in Germany shows that the spillover ratio increases more than proportionally when the announced path of future interest rates is extended by one year (see Chart 4). The effect becomes much smaller when the interest rate path is modelled as a series of one-year announcements (bars labelled “myopic”) or when households and firms in the model discount the future impact of the expected real interest rate on current consumption and investment decisions (bars labelled “disc.”).[22] This sensitivity analysis suggests that the size of spillovers under an expected path of unchanged interest rates, as shown in Section 3.2 and found in the literature, should be taken as an upper bound.

Chart 4

Model simulations of fiscal spillovers (with different monetary policy rules)

Spillover ratios to other euro area countries for an increase in public investment in Germany

(percentage change in GDP in recipient country as ratio of the percentage change in German GDP)

Source: The EAGLE model.

Notes: The chart shows four-year average spillover ratios of an increase in German public investment by 1% of GDP for four years, with different monetary policy rules: with responsive interest rates (bar labelled “normal”) and with no expected change in interest rates over different time horizons (bars labelled by the number of years interest rates do not react). The expected unchanged interest rates are modelled as a one-time announcement (yellow bar), a series of one-year announcements (bars labelled “myopic”), or a one-time announcement with households and firms discounting the future impact of the real interest rate on current consumption and investment decisions (bars labelled “disc.”).

4 Conclusions

The article analyses the main transmission channels of the spillovers of national fiscal policies to other countries within a monetary union. Estimates based on a new dataset confirm the findings of earlier studies that fiscal action can have positive spillovers among the largest euro area countries. Expenditure measures in one of the four largest euro area countries have generally a positive but low spillover effect on output in the other countries. This effect can become larger if more countries simultaneously undertake fiscal action.

The small size of fiscal spillovers supports the case for a central fiscal capacity. The reaction of interest rates is an important determinant for the magnitude of spillovers. An illustration using a Taylor rule shows that spillovers are small if interest rates react to the changes in inflation and output induced by fiscal policy, but the effects are amplified if interest rates are not expected to react to a fiscal shock. This reinforces the case for countries in a monetary union to pursue countercyclical fiscal policies in good times, building up fiscal buffers and a sound fiscal position that can be used to stabilise the economy in downturns. In addition, the fact that fiscal spillovers are generally small also suggests that a central fiscal capacity may be an important mechanism to enhance domestic fiscal policy effects.

- For more information on the debate on the euro area fiscal stance, see the article “The euro area fiscal stance”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2016, and Bańkowski, K. and Ferdinandusse, M., “Euro area fiscal stance”, Occasional Paper Series, No 182, ECB, 2017.

- For a discussion on risk sharing in EMU, see Cimadomo, J. Hauptmeier, S., Palazzo, A.A. and Popov, A., “Risk sharing in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB, 2018.

- Non-standard monetary policy measures that can lessen the constraints of the effective lower bound are not considered in this analysis.

- Spillovers from changes in fiscal revenues, which are not the focus of the article, are usually estimated to be considerably lower than government expenditure spillovers. The reason is that a tax cut impacts aggregate demand through the spending and saving decisions of households and firms, which induce more delays and uncertainty than the direct effect of an increase in government spending. For a review of the transmission channels of fiscal spillovers and their macroeconomic impact during the fiscal consolidation in the euro area countries in 2010–13, see Attinasi, M.G., Lalik, M. and Vetlov, I., “Fiscal spillovers in the euro area: a model-based analysis”, Working Paper Series, No 2040, ECB, 2017.

- See Beetsma, R., Giuliodori, M. and Klaassen, F., “Trade spill-overs of fiscal policy in the European Union: a panel analysis”, Economic Policy, Vol. 21, Issue 48, 2006, pp. 640–687.

- See International Monetary Fund, “Cross-border impacts of fiscal policy: Still relevant?”, World Economic Outlook, 2017.

- See Auerbach, A.J. and Gorodnichenko, Y., “Output Spillovers from Fiscal Policy”, American Economic Review, Vol. 103, No 3, 2013, pp. 141–46. For a comparison of the results of the IMF study and Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, see Blagrave, P., Ho, G., Koloskova, K. and Vesperoni, E., “Fiscal Spillovers : The Importance of Macroeconomic and Policy Conditions in Transmission”, Spillover Notes, No 11, International Monetary Fund, 2017.

- The effective lower bound is identified as interest rates being in the lowest quartile of the distribution.

- See, for example, International Monetary Fund, “Cross-border impacts of fiscal policy: Still relevant?”, World Economic Outlook, 2017, and In ‘t Veld, J., “Public Investment Stimulus in Surplus Countries and their Euro Area Spillovers”, Economic Briefs, No 16, Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission, 2016.

- For more information on the methodology and results of the estimates presented in this section, see Alloza, M., Burriel, P. and Pérez, J.J., “Fiscal policies in the euro area: revisiting the size of spillovers”, Documentos de Trabajo, No 1820, Banco de España, 2018.

- For Germany and Italy we combine official information from the quarterly non-financial accounts for general government statistics (ESA 2010 and ESA 95) and extend it backwards using intra-annual monthly fiscal information and annual official statistics. For the cases of Spain and the euro area, we obtain our data from updated versions of de Castro, F., Martí, F., Montesinos, A., Pérez, J.J. and Sánchez-Fuentes, A.J., “A quarterly fiscal database fit for macroeconomic analysis”, Review of Public Economics, Vol. 224, Issue 1, 2018, pp. 139-155, and Paredes, J., Pedregal, D.J. and Pérez, J.J., “Fiscal policy analysis in the euro area: Expanding the toolkit”, Journal of Policy Modeling, Vol. 36, Issue 5, 2014, pp. 800-823, respectively, which were constructed according to the methodology described above and are also consistent with national accounts. Data for France are obtained directly from Eurostat.

- Nominal variables are converted to real terms using the GDP deflator.

- See Blanchard, O. and Perotti, R., “An Empirical Characterization of the Dynamic Effects of Changes in Government Spending and Taxes on Output”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, Issue 4, 2002, pp. 1329-1368.

- See Jordà, O., “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections”, American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No 1, 2005, pp. 161-182.

- The destination spillover is the response to a simultaneous increase of €1 in the rest of the countries considered, which results from adding the effect of different fiscal shocks at the same moment in time. Hence, the results for this specification are likely to represent an upper bound.

- See Alloza, M. et al (2018), for results. Government spending spillovers by origin are estimated to be stronger in Italy and Spain than in Germany, but not significant for France. Spillovers by origin are found to be stronger for public investment than consumption.

- The Euro Area and Global Economy (EAGLE) model is a multi-country dynamic general equilibrium model of the euro area developed by an ESCB team composed of staff from the Banca d’Italia, Banco de Portugal and ECB. See Gomes, S., Jacquinot, P. and Pisani, M., “The EAGLE. A model for policy analysis of macroeconomic interdependence in the euro area”, Economic Modelling, Vol. 29, Issue 5, 2012, pp. 1686-1714.

- See Clancy, D., Jacquinot, P. and Lozej, M., “Government expenditure composition and fiscal policy spillovers in small open economies within a monetary union”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Vol. 48, 2016, pp. 305-326.

- In this and the following model simulations, the size of the stimulus (1% of GDP of the country or countries conducting the stimulus) is chosen for convenience in the interpretation of the results.

- The exercise is restricted to fiscal shocks and does not take into account other shocks that would have led to forward guidance, such as depressed private demand and credit-constrained households and firms following an economic crisis. From a longer-term perspective, an increase in public investment could generally be expected to contribute more to the productive capacity of the economy than government consumption. For a discussion of the quality of public finances, see “The composition of public finances in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 5, ECB, 2017.

- “Standard monetary models imply that far future forward guidance is extremely powerful: promises about far future interest rates have huge effects on current economic outcomes, and these effects grow with the horizon of the forward guidance”: McKay, A., Nakamura, E. and Steinsson, J., “The Power of Forward Guidance Revisited”, American Economic Review, Vol. 106, No 10, 2016, pp. 3133-58.

- See McKay, A., Nakamura, E. and Steinsson, J., “The Discounted Euler Equation: A Note”, Economica, Vol. 84, Issue 336, 2017, pp. 820-831.